The following is the first installment of a lecture delivered to the faculty and students of the Research Platform on Religion and Transformation from the University of Vienna at Melk Monastery (Austria) on July 26, 2016. The second installment will be published on Aug. 29. Select portions of this essay appeared earlier in the online publication Political Theology Today.

I.

In my book Force of God: Political Theology and the Crisis of Liberal Democracy, published last year by Columbia University Press, I argue that the current global crisis of liberal democracy is a “crisis of representation.” In some ways, this statement is both tautological and gratuitous. The question of liberal democracy as we understand it historically is all about the problem of “representation.”

Contrary to Rousseau’s effort to radicalize social contract theory with his postulate of the volonté générale, or “general will”, which as many critics have rightly noted can easily be misconstrued as an argument for totalitarian control of all features of society (the Nazi Gleichschaltung), we have lived through almost three centuries now when political theory, epistemology, and theology have been aligned around the late Medieval trope of a reflexive relationship between words and things.

The trope of an intimate correlation between words and things — verba and res, les motes et les chose, Wörter und Dinge — as the framework for what in the history of philosophy has come to be known as “correspondence theory” harks back to ancient Athens, where democracy was born. The ancient crisis of democracy ultimately derived from the struggle between Socrates and the Sophists, between Platonism and the cheap kind of conceptual relativism associated with a crude nominalism, which the latter hawked in the agora.

These epistemological debates, persisting in some guise for millennia, have never been esoteric preoccupations for cloistered thinkers removed from the “practical” affairs of Western political theory. They are founded on the commensurability between to logos and ta onta, between an ordering of speech in accordance with what we consider to be reliable markers of reference between what we say and what we experience.

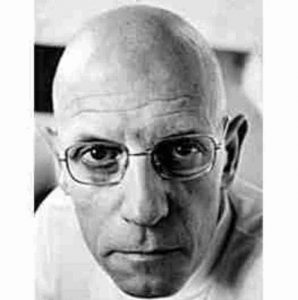

Such a linguistic ordering in a primordial way is also inseparable from the articulation of “law” or nomos, the very architecture of common life which for eons has been severed from its instinctual signaling of collective solidarity, its Blut und Boden tribalism. The common life demands an account that is given within the discursive formations that are appropriate to its age, its episteme in Foucault’s terminology. It is unsustainable without the power of logos, on which even the most rudimentary form of the polis is founded.

Foucault begins his famous “archaeological” inquiry entitled Les Motes et Les Choses (in English The Order of Things) with the recognition that all representational systems on which “knowledge” — and by extension all social and political speculation — is dependent on reliable and consensual methods of classification. “Our culture,” he writes, “has made manifest the existence – of order, and how, to the modalities of that order, the exchanges owed their laws, the living beings their constants, the words their sequence and their representative value; what modalities of order have been recognized, posited, linked with space and time, in order to create the positive basis of knowledge as we find it employed in grammar and philology, in natural history and biology, in the study of wealth and political economy.”1

But what happens when this reflexive, or reflective, relationship breaks down because of the episodic and involuntary intermixing of cultures, grammars, and conventions of discourse, as we have seen in terms of thoroughgoing social breakdown and disorder resulting form the geographical dislocations of peoples as well as mass migrations, such as the Völkerwanderung that changed the face of Europe entirely from the late fourth through the eleventh centuries?

The political crisis and the representational crisis turn out to be conjugate and dependent variables with each one thoroughly interwoven with the other. The upshot is not only a new language and new expressions of nomos. This sudden, disarticulation of the reflexive relationship between “words and things” is experienced as what Foucault terms “heterotopia,” an increasingly disjunctive or “deconstructive” method of dealing with and denoting what is the most familiar furniture of everyday reality.

In the political and social such a disarticulation has profound practical consequences. It can easily be construed as strife and chaos.

II.

What we are witnessing today is not only the climax of a long-burgeoning crisis of liberal democracy itself but the tremors of a gigantic crackup of an international system of previously well-functioning ideals and values, which are as much cultural and political as they are economic. The global crisis of  political democracy, therefore, emanates from the jumbling of categories used in the machinery of the most “sacred’ referencing systems that delineate fundamental world views and constitute the semiotic cement of human solidarity — the idioms of “justice”, the language of God, or the discursive norms for how we talk meaningfully about the “political” as a whole.

political democracy, therefore, emanates from the jumbling of categories used in the machinery of the most “sacred’ referencing systems that delineate fundamental world views and constitute the semiotic cement of human solidarity — the idioms of “justice”, the language of God, or the discursive norms for how we talk meaningfully about the “political” as a whole.

Everything is up for grabs. Multiculturalism, for example, undermines the sense of identity that hitherto had been the bedrock of national consciousness. Amid the so-called “clash of civilizations”, therefore, even so-called “human rights” are relativized and regarded merely as “Western.” They can be contrasted, for instance, with the “Islamic” take of what it means not only to be human, but also to have such “rights.” Instead they are regarded as “colonial” or “Orientalist” constructs that must be unmasked as mere ideologies.

This new kind of taxonomy is in many ways, as Foucault has driven home to us, the outgrowth of a new philosophical sophistication about the strategic role of language. Just as Jacques Lacan took structural linguists and used it as a psychoanalytic boring device to lay bare the inevitability of scission, fracture, or “lack”, in the imagined unity of desire and enunciation, so Foucault was able to see through the subterfuge of formal logic and the belief in a “universal” structure of communication to demonstrate how the so-called “linguistic turn” in late modern philosophy was but a subtle testament to the long-brewing crisis of representation.

Foucault’s early explorations of the close relationship between history, language, and knowledge become his later semantic operating system for the analysis of post-industrial society. In essence, Foucault’s approach in such works as The Archaeology of Knowledge and Madness and Civilization morphed slowly into a powerful cultural-hermeneutical collection of tools for mapping and diagnosing the symptomatology of what has come to be known as “ neoliberalism.”

The concept of neoliberalism is one that has arisen, especially since the end of the Cold War, as both a general economic descriptor and a quasi-political and critical-theoretical notion for explaining both the nature and effects of globalization. There is growing agreement among scholars that Foucault in his lectures at the Collège de France delivered from the late 1970s to his death in 1984 was the first to identify the underlying forces and factors that we now know as neoliberalism.

During his slowly evolving historical study of the transition from what he called “the disciplinary society” to the advent of “biopower” Foucault deftly made us aware that the forms of social control and political authority in the post-industrial period cannot be merely reified as some kind of axis of “power/knowledge” without examining their semiotic makeup, that is, the way they function in a garden variety context as interoperable sign-processes. Even “economic” processes can no longer be taken apart in the way they were in Marx’s day as mere “dialectical” or material phenomena. They must be seen as modalities of linguistic rule-making which both precede and provide the final shape for the “objects” of political criticism and cultural change-making.

Why does any of the foregoing really matter? The last few months have been tumultuous and unnerving for the proverbial “global elites” who, according to the newly fashionable discourse, comprise the minions for what is alternately termed “international capitalism” or “neoliberalism.” The nomination of Donald Trump for President of the United States and the shock of the Brexit vote in England have set off a squall line of on-the-spot, overwhelmingly reactive commentary all across the ideological spectrum, ranging from a newly vocal self-confidence on the part of what has come to be known as the “alt-right” (which one writer has defined as “a motley crew of sub-cultural political identities consists of the conservatives, identitarians, dissidents, radicals, outcasts, anarchists, libertarians, neo-reactionaries, and other curious political formations”) to the kind of anti-egalitarian hysteria epitomized in James Traub’s rant in Foreign Policy that “it’s time for the elites to rise up against the masses.”

At the same time, there have been tentative, and often fumbling, efforts to cast what is happening in more encompassing, analytical terms than merely slinging in the familiar, thought-stupefying clichés about dark, atavistic insurgencies fired by “racism” or “populism” or “nativism” or “nationalism” or even “fascism.” Predictably, these diagnoses have been couched in the jargon of neo-liberal economism – wage stagnation, income inequality, the outsourcing of manufacturing, the domination of elections by “big money”, insufficient government spending on education or job retraining, etc. And the “cultural” side of the equation, manifested in anti-immigrant sentiment among the working classes along with a supposed rejection of “global elites” and “cosmopolitanism,” is routinely blamed on the inherent character defects of the insurgents themselves – their parochialism, their entitlement, their “white privilege,” their ignorance, their social and moral backwardness, their susceptibility to demogoguery, and on and on.

The economic dislocations that are allegedly causing what French far-right party leader Marine LePen with signature bluster termed a “populist spring” (invoking obviously false analogies to what happened in the Middle East starting in 2011) have not all of a sudden become apparent, even to the “experts” or to the populace at large. They have been visible and full-blow since the financial crisis of 2008, and were even predicted by some savvy economic seers since the turn of the millennium. The conventional wisdom that it is the lack of “real income growth” since the Great Recession that has all at once amped up popular frustration belies a more subtle and diffuse structural dynamic within the global order that these knee-jerk economistic explanations are incapable of bringing to light.

Radicals and those who call themselves “progressives” these days are accustomed to laying the blame for the crises, injustices, and social and political dysfunctions of our time at the feet of two rough beasts that are alternately named as both “capitalism” and “neoliberalism.” Often, the two are rhetorically conflated as one. The problem with this conflation, as the key theoreticians of the latter such as Foucault and David Harvey have repeatedly showed us, is that the former historically from Smith through Marx onward has functioned largely, although not exclusively, as an economic construct, whereas the latter is a term saturated with various unrecognized political significations and hidden intentionalities, thus betraying its hybrid nature.

“Neoliberalism” is not a term that can be simply interchanged with “capitalism,” a word to which Marxism gave a kind of overdetermined meaning and which is becoming less and less useful as a descriptor, other than to name the obvious, a complex and expansive worldwide webwork of markets and financial mechanisms that power them.

Neoliberalism is really not about economics, but about values, (as I argued extensively in Force of God) instantiating them in almost invisible routines of symbolic exchange that have profound economic effects. The “economic” form of neoliberalism, as we are beginning to realize, is a merely a contingent manifestation of what Foucault dubbed the biopolitical means of “governmentality”. Ever since Adam Smith we have derived the familiar types of political organization from economic means of production and distribution (as implied in the eighteenth century concept of “political economy).”

Thus a productive analysis of neoliberalism requires in many ways, as Maurizio Lazzarato has made  clear to us, an investigation into the value-sources of our social and economic condition — a good, old-fashioned, Nietzschean “genealogy of morals.” According to such theorists as Foucault, Harvey, and Lazzarato, neoliberalism (taking into account their different degrees of emphasis) amounts to a configuration of power relations in an expressive articulation of embedded social valuations which, in turn, frequently employ the rhetoric of economicism — and economic “well-being” — both to mask the reality of elite domination and to exploit the humane instincts of those who are dominated. In short. homo neoliberalismus only wears the colorful costumes of classical homo economicus.

clear to us, an investigation into the value-sources of our social and economic condition — a good, old-fashioned, Nietzschean “genealogy of morals.” According to such theorists as Foucault, Harvey, and Lazzarato, neoliberalism (taking into account their different degrees of emphasis) amounts to a configuration of power relations in an expressive articulation of embedded social valuations which, in turn, frequently employ the rhetoric of economicism — and economic “well-being” — both to mask the reality of elite domination and to exploit the humane instincts of those who are dominated. In short. homo neoliberalismus only wears the colorful costumes of classical homo economicus.

Like Frank Baum’s Wizard of Oz, homo neoliberalismus is a grand illusionist who manipulates our willingness to be enchanted by what Nietzsche called the “highest values” to our ultimate servitude. Every historical form whereby this articulation is made manifest consists in what Foucault called a dispositif, an “apparatus” whereby power, knowledge, discourse, and personal inclination are mobilized and intercalated to produce such a magic theater of signs, what Michael Lerner has termed without irony the “politics of meaning.”

Neoliberalism is the munificent politics of personal meaning in the late era of consumer capitalism that masquerades as an old-style conservatorship of economic interest (consider the constant polemical sop of preserving the “middle class”), while relentlessly encumbering through an endless financialization of their private wherewithal and assets (credit cards, mortgages, student loans, taxes) that become the sole “property” of banks, hedge fund managers, and “crony capitalist” allies within government.

Just as the double-sided dispotif of the Middle Ages was the castle on the hill (protecting town and manor against the armies of rival feudal lords) and the cathedral (building thick stone fortifications to insulate the unity of the holy catholic faith against the wiles of the devil), and in the industrial era it was the factory with its concentration of productive power supposedly protecting the social order against want and idleness, in the twenty-first century it has become the corporate-university-financial-information complex, leveraging some of the most insidious and efficacious strategies of Foucauldian biopower to guarantee globally diverse populations not just the “democratic” delights of self-improvement and personal advancement, but a solid defense against all the terrors and predations that have gone before in human history.

These defenses are not merely virtual. They involve real weaponry, usually to protect whole populations as has been the case in large part of most Western military interventions since the 1950s. To quote Foucault: “Wars are no longer waged in the name of a sovereign who must be defended; they are waged on behalf of the existence of everyone.”2 The idea that wars can be fought simply for conquest, or to shield sovereignty from whatever threatens it for whatever reason, defers now to a conviction that blood and treasure must be expended only for higher, binding “humanitarian” moral purpose, to which the occasional United Nations interventions authorized by the Security Council consistently call our attention.

Kantian morality in its more diffuse and global-political guises becomes the subtle template for a new universalistic biopolitics rotating around the Foucaldian double axis of “power/knowledge”. The same

holds true for “domestic struggles” and the challenges of civil society where actual armaments are only deployed in the most extreme instances. The vast taxing, regulatory, and welfare apparatus of the state replaces classical raison d’etat, and the new “governmentality” of neoliberal biopower whose coercion is primarily “discursive” supplants the disciplinary systems of the moribund industrial order.

The power of “moral shaming”, which in an earlier era was available only to political and social leadership with its privileged access to broadcast communications, now is extended to the masses through social media who, while believing themselves to be masters of their own opinions, dutifully carry out the “soft-coded” value imperatives of the neoliberal hegemony.

As Foucault so brilliantly brought to light in his Collège de France lectures, the advent of biopolitics in the modern age is the result of a long, sequestered, yet inexorable evolution of the valorization of what he calls the “pastorate” in Western culture. For Foucault, who relies more on Nietzsche than many of his current readers are wont to acknowledge, the pastorate are the custodians of what the latter famously dubbed the “moral-Christian” metaphysics that has suffused Western epistemology from Plato forward. The pastorate encrypts the real in terms of a signifying praxis of ethical responsibility for the lowly, the mediocre, and the ordinary, all the while elevating the “priestly” function of guilt assignment and assuaging in such a manner that curial power is perpetually reinforced and multiplied.

This kind of “revaluation” of values, which according to Nietzsche can be traced back to the Christian church in its earliest instantiations, elevates confession over innocent vitality, self-abnegation over self-affirmation, systemic social distributions of Hegel’s “unhappy consciousness” with its irremediable guilt psychology that are endlessly absolved and administered by way of spiritual triage by the pastorate itself. Foucault writes that from the late Middle Ages all the

…struggles that culminated in the Wars of Religion were fundamentally struggles over who would have the right to govern me, and to govern them in their daily life and in the details and materiality of their existence…This great battle of pastorship traversed the West from the thirteenth to the eighteenth century, and ultimately without ever getting rid of the pastorate.3

Once the promise of heaven dissolves into the various secular heterotopias for the “pursuit of happiness” from the Enlightenment onward, the pastoral oversight of spiritual credits and debits is transformed into the benevolent biopolitics of the liberal state.

In short, the battle for democracy, beginning with the English Revolution in the 1640s was both an insurgency against the clerical “pastorate” as the proto-structure of biopolitics in the West and at the same time a campaign to install new mechanisms of biopower in the form of various “republics of virtue,” such as Cromwell’s Protectorate, Robespierre’s National Convention, and even Lincoln’s authoritarian redesign of the federal government around militant Christian nationalism during the American Civil War. Bismarck’s Staatssozialismus, though not an obvious example of democratic biopolitics, can be added to this list, insasmuch as it laid the groundwork for the full governmental appareil of the secular pastorate in the twentieth century.

Carl Raschke is Professor of Religious Studies at the University of Denver, specializing in Continental philosophy, art theory, the philosophy of religion and the theory of religion. He is an internationally known writer and academic, who has authored numerous books and hundreds of articles on topics ranging from postmodernism to popular religion and culture to technology and society. Recent books besides Critical Theology include Force of God: Political Theology and the Crisis of Liberal Democracy (Columbia University Press, 2015) and The Revolution in Religious Theory: Toward a Semiotics of the Event (University of Virginia Press, 2012). His previous two books – GloboChrist (Baker Academic, 2008) and The Next Reformation (Baker Academic, 2004) – examine the most recent trends and in paths of transformations at an international level in contemporary Christianity. Faith and Reason: Three Views (IVP Academic, 2014), of which he is a co-author, is a conversation among three contemporary Christian philosophers. Finally, he is current managing editor of Political Theology Today and senior editor for The Journal for Cultural and Religious Theory.

______________________________________________________________________

1 Michel Foucault, The Order of Things (New York Routledge, 20015), xiii.

2 Michel Foucault, History of Sexuality I , trans. Robert Hurley (New York: Random House, 1980), 137.

3 Michel Foucault, Security, Territory, Population: Lectures at the Collège de France 1977–1978 (New York: Picador, 2009), 149.