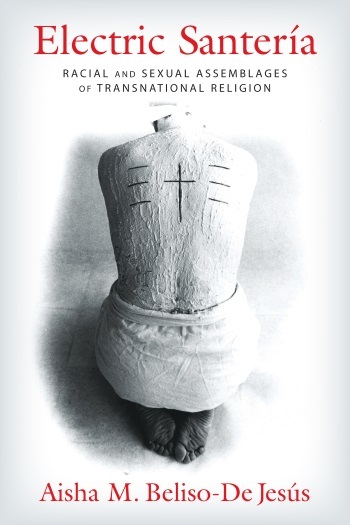

Beliso-De Jesús, Aisha M. Electric Santería: Racial and Sexual Assemblages of Transnational Religion. New York: Columbia University Press, 2015. ISBN-10: 0231173172 Hardcover, paperback, e-book. 304 pages.

Beliso-De Jesús, Aisha M. Electric Santería: Racial and Sexual Assemblages of Transnational Religion. New York: Columbia University Press, 2015. ISBN-10: 0231173172 Hardcover, paperback, e-book. 304 pages.

Aisha M. Beliso-De Jesús’ 2015 book Electric Santería: Racial and Sexual Assemblages of Transnational Religion begins and ends with an intimate account of her relationship with Alfredo Calvo Cano, or simply Padrino (godfather), as he was referred to by his followers who learned to navigate their space in an increasingly transnational world through devotion to his guidance in Santería and other “African-inspired” Cuban religions. Beliso-De Jesús was one of those followers, and the book is inevitably shaped by her simultaneous proximity to the object of her study, as a practitioner raised in the traditions, and her distance from it as an anthropologist born, not in Cuba, but the United States.

Beliso-De Jesús – whose writing style is sometimes reminiscent of Robert Orsi’s groundbreaking Between Heaven and Earth[1], but with more engagement with critical theoretical texts – does not offer herself as a distant and objective observer but rather, following Martin Holbraad[2], describes her engagement as an “ontography” in which, “anthropologists take the ontological questions of their subjects’ own modes of understanding truth as the first premise, this intervention continues to naturalize the ethnographer as exterior to what she studies” (25). This stance, then, allows her to locate her work within the bounds of Gayatri Spivak’s ethical imperative to question one’s subject without paralyzing it in a power dynamic laden nexus of representation. Instead she insists that, “understanding coming into being through copresences shows how the positions of researcher and interlocutor both infect and affect – haunting, negotiating, and penetrating in ways that are never fixed or without power” (26-27).

This notion of copresences is central to Beliso-De Jesús’ work. It is her way of speaking of the potent, and even electric, sites of affective transformations that transgress national, social, and religious boundaries. “Copresences,” she writes, “are sensed through chills, shivers, tingles, premonitions, and possessions in and through transnational Santeria bodies and spaces.” And she adds that they “are active spiritual and religious subjectivities intimately tied to practitioners’ forms of movement, travel, and sensual bodily registers” (7). It is this conceptual framework that allows her to give voice to the affective relationship between practitioners and the Oricha (saints) at the level of transnational transgressions, without appealing to transcendent mediation.

In fact, the book according to Beliso-De Jesús, is, in part, a response to J. Lorand Matory’s question about what it might look like to rethink transnationalism and globalization through the ontologies of “spirit possession religions” as opposed to only “Abrahmic and karmic religions.” Beliso-De Jesús states that, “[t]hey are forms of nontranscendental transnationalism. Like the ‘wave-particle’ paradox, which understands the world as intraconnected, Santeria relationality does not collapse difference.” She adds, however, that, “it is important to not presume that copresence relationality should be uncritically celebrated as an inherently subversive site” (219).

The relational ontology of copresences, which resembles something like Karan Barad’s “relationality without relata[3],” is the means by which individuals and communities negotiate the complex, and often paradoxical, world of imperialism and resistance in Cuba and abroad. They enact what Luis Leon calls “religious poetics”[4] – the process by which practitioners engage in their socio-economic setting by way of creative and often improvised materializations of their inherited religious traditions – based in the entangled ontologies which both produce and are produced by Afro-Cuban religious subjects. Beliso-De Jesús’ method, which is deeply transdisciplinary, seems to even enact a sort of poetics of its own. It can best be described as “reading diffractively,” to again borrow from Barad, in which, rather than engage in straightforward critique, scholars’ writings and practitioners lived experiences can be read “through each other,” and, as Beliso-De Jesús adds, can be seen as copresences themselves. (13)

It is worth mentioning that if a reader approached this book without any prior engagement with Santeria and other “African-Inspired traditions,” to use the preferred nomenclature of Todd Ochoa in Society of the Dead, then they would not necessarily have a clear understanding of these traditions upon finishing it. This is because Beliso-De Jesús is not interested in offering an accessible introduction to these traditions. Instead, Electric Santería offers a sustained and nuanced engagement with the operative metaphysics of these traditions and how they are navigated in the lives of practitioners and communities.

It is worth mentioning that if a reader approached this book without any prior engagement with Santeria and other “African-Inspired traditions,” to use the preferred nomenclature of Todd Ochoa in Society of the Dead, then they would not necessarily have a clear understanding of these traditions upon finishing it. This is because Beliso-De Jesús is not interested in offering an accessible introduction to these traditions. Instead, Electric Santería offers a sustained and nuanced engagement with the operative metaphysics of these traditions and how they are navigated in the lives of practitioners and communities.

The evidence that she provides to support her claims in each chapter are organized along the lines of a series of “scapes,” in the sense that Arjun Appudari[5] uses to describe them. The “scapes” can be understood as rhizomatic assemblages, or “affective territorialities that do no remain fixed” (13). Instead, they are constantly changing, prompting a kinesthetic analysis that allows Beliso-De Jesús to trace the flows of copresences, as a kind of electric energy, through media, travel, notions of authenticity, and even olfactory affects.

In the first chapter, Beliso-De Jesús argues that “the electrical waves of oricha [saints] and egun [spirits of the dead] call for a reconfiguration of anthropological understandings of media and religion” (43). She explores this possibility through the use of video media in the transnational transmission of Santería. In her research she finds that practitioners often describe being possessed by spirits through the medium of videos of Cuban rituals that are often sold to practitioners and initiates in the United States – an experience made possible through the operative metaphysics of Santería, in which electric energies that allow for possession are not mediated through the video medium, but rather are copresent, or entangled, in the very materiality of the tapes.

This practice, however, is a deeply divisive one. One interlocutor, referred to as Pastor, decries the commercialization of his tradition. He proclaims to Beliso-De Jesús that, “[o]ur ancestors were sold on chopping blocks and now our traditions are being sold on eBay!” (50) Thus, the transnational movement of Santería media becomes a productive site for negotiating racialized claims of authenticity in Beliso-De Jesús’ skillful analysis.

In the second chapter, Beliso-De Jesús explores what she calls transnational caminos (pathways). Transnational caminos are the shifting roads that practitioners of Santería find themselves on and the ways in which these places become copresent with those who traverse them. Building on the work of tourist studies and Elizabeth Povinelli’s notion of “geontologies,” Beliso-De Jesús considers the haunting copresences that become entangled with bodies and objects around and across international and cultural borders in a way that produces both opportunities for poverty stricken and racially marginalized populations and provides the conditions for their exploitation.

Beliso-De Jesús explores the emergence of racialized and sexualized spaces and subjects in relationship to how Afro-Matanceros in Matanzas negotiate claims of authenticity and power through their unique style of Afro-Cuban traditional culture in the third chapter. Mantazas itself is deeply marked by its history as a site of resistance for African slaves, and therefore, as a site of colonial brutality as well. Likewise, “Matanceros,” our author writes, “situate their regional-national authenticity as part of their broader link to blackened copresences – ways of being in and seeing the world that is unique due to the city’s history of racial rebellion and religious inspiration” (123). Even here, however, we are warned that “Santería is not… an example of pure resistance,” to the forces of colonialism (144). Rather, the blackened geography of Mantazas offers its Santería practicing inhabitants a claim of authentic power that simultaneously reifies their abjection. This produces what Beliso-De Jesús calls a “racialized queerness” – drawing on her definition of queerness as “an ontology of being-strange-in-the-world” (145) – in which subjects who do not fit into clean and tidy analyses of power emerge.

The fourth chapter on smellscapes – in which practitioners enact a complex and constantly shifting religious poetics to negotiate senses of authenticity, tradition, and boundary markers that can both reify and subvert national, racial, and sexual norms – is perhaps the most interesting and imaginative section of the book. Building on the work of tourist scholars who have insisted that “meaningful distinctions are usually first sense through the nose” (147), Beliso-De Jesús explores how the olfactory experience of Cuban Santeria is coded by notions of race, class, gender, and sexuality. In Santeria, smell is not only tied to memory. “[S]cents also conjure copresences,” she writes, noting that, “[c]ertain smells bring different spirits and oricha into particular places” (174). Beliso-De Jesús makes a compelling case, not only for how the olfactory is an important productive element of Santería, but for a more attentive focus on its affective power in decolonial and diasporic studies more broadly.

In the fifth and final chapter, Beliso-De Jesús turns her attention to the contemporary iyanifá (female priests of Ifá, the Yoruba, or West-African, system of divination) debate in Cuban Santería. In this contentious debate both sides rely on claims of authenticity and anti-imperialism to foster their arguments. In short, the African-style Cuban priests of claim that Cuban-style Ifá imported Western misogyny; likewise, the Cuban-style Ifá priests accused African-style Ifá of being contaminated by Western feminism. Through her analyses of this debate, Beliso-De Jesús argues that “these competing diasporic formations both deterritorialize and reterritorialize particular national spaces” (186). She emphasizes the way in which, what she calls contaminating feminities play a crucial role in the production of racialized and sexualized subjects. These contaminations – which can be seen as copresences in their own right – are crucial to what Sara Ahmed would call the affective economy of Cuban Santería, in which practitioners and communities negotiate claims of power and authenticity.

The book, as mentioned above, ends where it began: with Padrino Alfredo. The intimacy with which Beliso-De Jesús briefly narrates the death and legacy of her mentor harkens back to her insistence that, despite being a scholar, she is not simply an outsider to the world of Santeria. She, herself, is still clearly haunted by the transnational copresences that her work both describes and is contaminated by. This allows her to produce a book that is not only a fine work of scholarship, but an engaging and compelling read as well.

Ryne Beddard is a graduate student in Religious Studies at the University of Denver. He will begin doctoral work at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill in the Fall of 2017. Ryne would like to thank Dr. Luis Leon’s Latino Religious Cultures class at the University of Denver for their helpful discussion and insights regarding this book.

[1] Robert Orsi, Between Heaven and Earth: The Religious Worlds People Make and the Scholars who Study Them, 2005.

[2] Martin Holbraad, “Ontography and Alterity: Defining Anthropological Truth,” 2009.

[3] Karen Barad, Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning, 2007.

[4] Luis Leon, La Llorona’s Children: Religion, Life, and Death in the U.S.-Mexican Borderland, 2004.

[5] Arjun Appadurai, Modernity at Large: Cultrual Dimensions of Globalization, 1996.