Many kinds of structures seem ubiquitous and essential for the kind of meaning humanity concerns itself with. Lévi-Strauss’ early work on myth and kinship are two significant examples with the influence of each visible in much of our daily existence. Still, we must ask, can structures of this sort be universal? How do we avoid incorrectly applying structural knowledge in a tacit act of domination? Even more worrying, how do we maintain awareness of these structures and their influence over us?

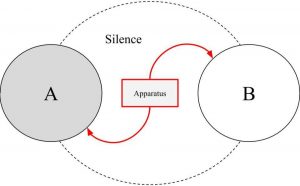

I argue that a reimagining of the notion of silence as more than a sonic phenomenon is needed to address the dominant structural apparati of Western discourse. There is a kind of cultural silence that exists within many, if not all societies. This silent space is devoid of overt ideologies, direct systems of valuation, and blatant attempts to influence others. Due to the vacuum present in such a space, it is where structural operations flourish, nestled within it as their many tendrils reach out and stealthily try to manipulate our thoughts, actions, and beliefs. They forge connections between things like ideology and social organization where one falls into the wake of the other and is shaped in a way that is nearly invisible to the passing glance.

A true apparatus, as Michel Foucault would call it, is formed in this silence. Rosalind Krauss’ treatment of avant-garde originality should be seen as a prescriptive approach to penetrating this alternative silence in order to accurately understand its nuances and implications. This is especially powerful when Giorgio Agamben’s study of apparati is treated as an intertextual explanation of Krauss’ methodology.

Four key thinkers will assist us in this task. Claude Lévi-Strauss laid the groundwork for the Structuralist methodology that we will see extrapolated and explored by the other three. Structuralism retrains our attention away from categorical understanding and instead points to relationality as key. John Cage introduces us to silence as a source of creative potential. While he arguably fails to address the danger inherent within silence when considered beyond sonic phenomena, his related work with indeterminacy reveals an effective path toward a liberation from oppressive structural operations. Giorgio Agamben’s study of the apparatus of the Christian confessional and the sacred–profane binary is enriched by the this notion of silence as “metasonic.”

Furthermore, the confessional serves as an example of the dangerous and powerful role that silence can play as a space where apparatuses connect, manipulate, and exploit various unrelated ideologies and experiences. Finally, we will see Rosalind Krauss exposing originality as a structural operation within avant-garde modernist art as she also provides a model of skeptical analysis which Cage appears to embody through his work on indeterminacy.

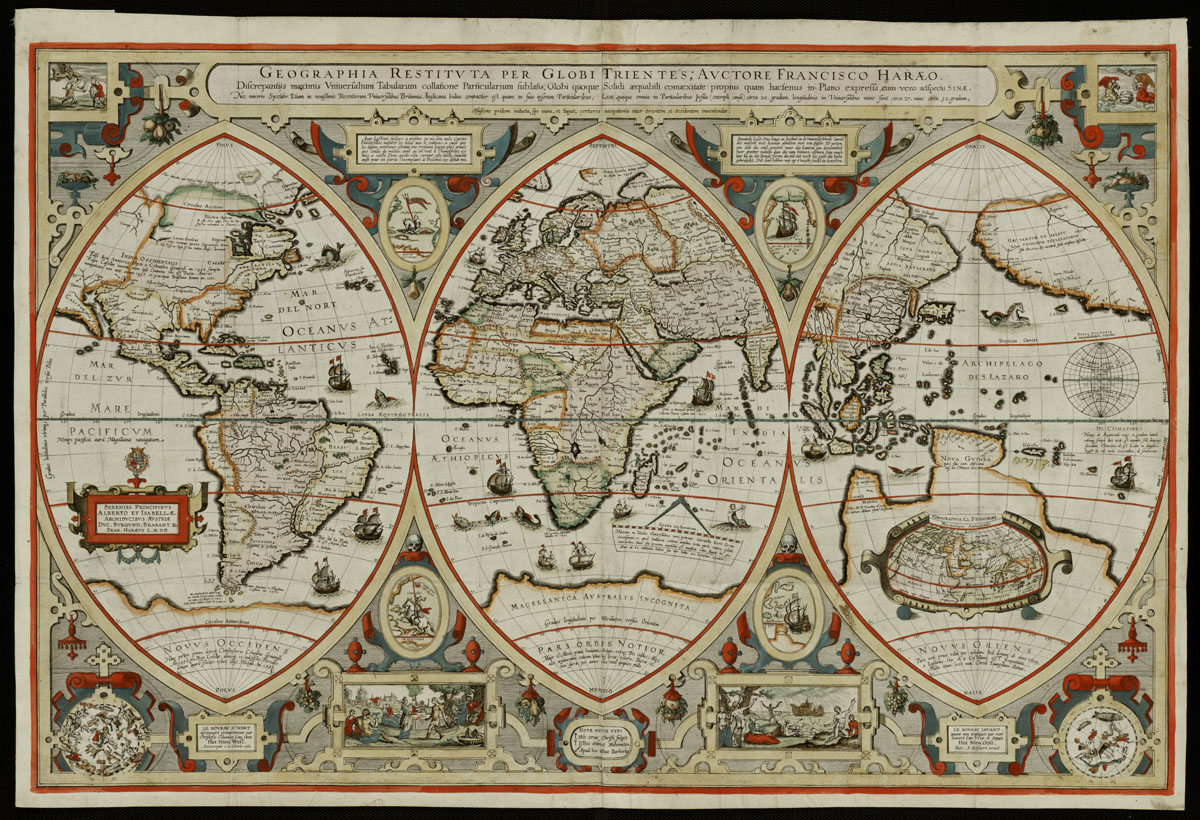

Let us begin with Lévi-Strauss to establish a solid foundation and familiarity with the structuralist approach which we can then repurpose toward this study of silence. According to Patrick Wilcken, the philosophical inspiration for structuralism came to Lévi-Strauss while out on a hike one day as he began contemplating the dandelions along his path. While studying their design, he realized that each one “was the result of the play of its own structural properties calibrated into a unique and instantly recognizable form.”[1] Instead of viewing the dandelion as defined by its categorical properties, Lévi-Strauss had the epiphany that those very categories were in fact formed by how the various aspects of the plant came together and interacted with each other. Wilcken offers a wonderful definition of structuralism as “the idea that culture, like nature, could have its own structuring principles—hidden, yet ultimately determining, like the genetic codes that provide the geometry of nature.” [2]

At the core of structuralist thought was this intense focus on relations over absolutes. In the explanation of his methodology, Lévi-Strauss’ first step was to “define the phenomenon under study as a relation between two or more terms, real or supposed.” [3] The goal was to uncover the hidden connections driving the form and behavior of the phenomenon. The same focus on relationality drives Cage’s own work while we also see Agamben and Krauss building on this methodology.

John Cage may be most famous for his controversial 4’33” composition which can appear to be nothing but utter silence, but this work along with others and his many writings problematize silence in a fascinating way. In his essays and lectures, the most valuable information about the notion of silence is implied rather than stated outright. This is fitting, actually, as it begins to reveal how silence can occupy more than just the sonic perception. In describing one of his works, Cage tacitly presents silence as a creative potential.

Though in the Music for Piano I have affirmed the absence of the mind as a ruling agent from the structure and method of the composing means, its presence with regard to material is made clear on examining the sounds themselves; they are only single tones of the conventional grand piano, played at the keyboard, plucked or muted on the strings, together with noises inside or outside the piano. [4]

Here, the absence of the mind is a metaphor for silence. He is seeking a way to remove the mind as the controlling agent and claims something more than what was done in Music for Piano must be pursued. [5] Silence/absence is tacitly presented as a realm of immense potential that is somehow difficult to reach and/or recognize. We see now that an extension of silence is needed to fully grasp the implications of Cage’s work. To begin, we must endeavour to view silence not as a structure in itself but as the space where structural operations occur. It can also be understood as a cultural space to which no one ideology or simple system lays claim. To illustrate, let us take a look at Agamben’s analysis of the confessional.

The confessional is an apparatus of violent self-subjectification. Let me clarify what is meant by both ‘apparatus’ and ‘self-subjectification.’ Agamben offers up Foucault’s definition of ‘apparatus’ from 1977 where he states that “the apparatus is precisely this: a set of strategies of the relations of forces supporting, and supported by, certain types of knowledge.” [6] Agamben extends this notion to anything that can exert some control over “the discourse of living beings.” [7] He also explores the notion of oikonomia, the Greek root of ‘economy,’ as the precedent for split or self-subjectification. The concept was used to justify the Holy Trinity in early Christianity by asserting the being, the ontology of divinity as separate from its action, its praxis, its oikonomia. [8] The silence of the confessional facilitates this oikonomia to be aimed at the human self instead of the divine.

The traditional confessional is defined by silence both phenomenally and metaphysically. Walking into the confessional booth, the already quiet space of the church fades away as the wood and fabric suck up nearly every bit of auditory distraction. Every remaining sound is drawn into clear focus as the mind searches for the familiarity of noise within that silence. The silence of the confessional reveals it the liminal space where no single ideology reigns. Lived actions are forced into direct conflict with a religious dogma that may not be applicable within that daily experience. It is the vacuum where ideologies connect and the void where apparati are born.

The profanation–sanctification function shows how this occurs. Agamben points to Ancient Roman law as the source for our notions of profanity. It is described by Trebatius as “that which was sacred or religious, but was then restored to the use and property of human beings.” [9] The relation between the profane and the sacred drives the confessional experience where one splits along a ‘sinful’ and ‘clean’ binary. [10] The ‘new’ self which is closer to sacred is thus pushed to regard the ‘old’ sinful self as a source of contamination, as the profanation of its own cleanliness and sanctity. The plurality of life where one is never purely clean nor purely sinful is denied as toxic to the dogmatic economy of the confessional.

All of one’s life lived outside of the confessional moment is potentially cast as fundamentally profane in contrast to the sacred monologism of a ‘pure’ self or soul. The silence which Cage identified as so ripe with potential, as demonstrated by the ambient noise that fills the silence of 4’33”, is instead drained to become a void. There, the apparatus is free to construct paradigmatic links between different spheres of being—material life and spiritual life—and the ideologies within them. It is able to manufacture the conditions of its own necessity.

This leads us to Krauss’ analysis of avant-garde originality as a demonstration of the skepticism needed to avoid becoming trapped within a repressive apparatus. Originality as an ideal within avant-garde art can be seen as the mystification of human labor. When Krauss points to the “myth of Rodin as the prodigious form giver” which carries with it images of Nietzsche’s Apollo, she implies as much. [11] It is even more fitting when she uses the phrase “cult of originality” to describe the pseudo-worship of Rodin’s works. [12] Even the connoisseur can be seen as the avant-garde equivalent of the seer where their ability to discern superior style and ‘genuine originality’ seen as equal to the elucidation of metaphysical truth from bones, runes, and tea leaves. Both are arbiters of a form of truth and both have the capacity to render the claims of another as wanting or fraudulent. [13]

It is as if we can see a performance of the apparatus of fine art befitting Agamben’s understanding of the term. All of this is, as Krauss points out, is rooted is the sanctification of “the self as origin,” as the site and fuel of human creation. [14] Krauss even explores the concept of the grid as a form caught between the realms of the profane and the sacred. She points to the grid as a “paradox” which simultaneously restricts the artist while giving them a space for aesthetic freedom. [15] Over their professional lives, artists can be seen dedicating more and more of their work to grids as visual media, but Krauss argues that this moves them away from originality in an absolute sense. Instead, repetition becomes the focal point of their process and product. [16] The paradox forms when the artist adopts the avant-garde view of mystical originality predicated on “his own self as the origin of his own singularity.” [17] This is then seen as the originary source for the work’s originality as an extension of this aspect of the artist.

A silence forms in the confusion and paradox of avant-garde artistry. The ideology of authenticity is separated by a chasm from that of the grid and geometry. The void between them is treated as a problem to be solved rather than a simple reality. So, the apparatus of originality forms within that silence and forces epistemic associations between the two that defy logic and rely on faith in the apparatus itself. The silence in question adopts the sanctity of originality and questioning it is thus rendered profane and reprehensible.

By rejecting the accepted dogmas of the avant-garde via proactive skepticism, Krauss is able to penetrate the apparatus of originality and the silence it fills. The theoretical work that takes place there fills that silence not with the forced connections of an apparatus, but with a blurring of the boundaries between authenticity and the geometric grid. We are called to accept each side of this relation for what it is, not what we wish it to be. We can better understand the application of Krauss’ approach as a life caught in the flux of action and contemplation that Cage also alludes to with his call for a new form of listening that is, as it core, the simple “attention to the activity of sounds.” [18] This requires the letting go of how one assumes we are meant to understand the familiar.

Krauss’ comments on modernist art criticism accepting things like the “opacity” of the painted surface as True is just the sort of thing we must challenge through this approach. [19] A lack of such skepticism breeds an absence/silence that invites the voiding power seen in Agamben’s study of the confessional. Through this “new listening” silence is addressed directly and filled with genuine discourse instead of dogmatic apparati. [20] Consider Cage’s Indeterminacy lecture comprised of sixty stories recited at a rate of one story per minute. In the preface, he describes the reason for its strange and unfamiliar structure.

My intention in putting the stories together in an unplanned way to suggest that all things—stories, incidental sounds from the environment, and, by extension, beings—are related, and that this complexity is more evident when it is not oversimplified by an idea of relationship in one person’s mind. [21]

This lecture gets us closer to an understanding of how to replace the emptiness of silence with the hum of white noise and indeterminacy, with the hum of lived life.

It is possible to read Cage as more incompatible with Krauss’ work than I have presented it here as he is an avant-garde composer and she is critiquing the avant-garde. Such a stance misses a crucial difference between Cage and many others of this movement. I see him as the authentic avant-garde more concerned with enacting his own aesthetic originality rather than performing the contrived conceptual originality that Krauss deconstructs. There is also the question of the validity of “metasonic silence”. Another way to view this concept and assuage such a worry is through the notion of ambiguity. The silence I am pursuing here is a metaphor for the areas of life where one is not quite sure what values or practices to follow. This absence of clear direction implies an absence of instruction which we can more viscerally understand through the metaphor of silence and the stark contrast it provides to the noise of daily life.

It was Lévi-Strauss who pioneered the structuralist method and rightfully drew our attention to the value of relationality as the way meaning is generated in human life. Cage introduces us to the immense potential of silence as a generative force and opens up the door to consider silence as a metasonic phenomenon. Agamben extends and elaborates Lévi-Strauss’ methodology and applies it to Foucauldian apparatuses and the effects of systems of sanctification and profanation.

Krauss gives a clear demonstration of how one can use skeptical structuralism to address epistemic assumptions like originality and the forces driving it. Returning to Cage, we see how artistic expression can play a role in facilitating the embrace of indeterminacy as a sort of flux one occupies that fully realizes the implications of relationality explored by Lévi-Strauss’ structuralism. By extending the notion of silence into a metasonic metaphor it becomes a powerful tool to address the many apparati of Western discourse. This approach is crucial in helping one learn to embrace the indeterminacy of life and the hazy relational structures that drive our existence.

Jonathan Morgan is a college educator, independent scholar, and PhD Candidate at the Institute for Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts (IDSVA). He specializes in craft theory, ontology, aesthetics, philosophy of mind, and cultural studies. His current work focuses on a radical rethinking of craft theory as a novel form of existential praxis that has been overlooked due to the hegemonic application of art theoretical methodologies to the study of craft. Much of this work centers on the lived experience of craftspeople more so than the objects they make.

[1] Patrick Wilcken, Claude Levi-Strauss: The Father of Modern Anthropology (Penguin Books, 2012), 118.

[2] Ibid., 118-119.

[3] Ibid., 257.

[4] John Cage, Silence: Lectures and Writings (Wesleyan University Press, 1961), 27.

[5] Ibid., 27-28.

[6] Giorgio Agamben, “What Is an Apparatus?” in What Is an Apparatus? And Other Essays, trans. David Kishik and Stefan Pedatella (Stanford University Press, 2009), 2.

[7] Ibid., 14.

[8] Ibid., 9-10.

[9] Ibid., 18.

[10] Ibid., 20.

[11] Rosalind Krauss, “The Originality of the Avant-Garde,” in The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1986), 155.

[12] Ibid., 155-56.

[13] Ibid., 156.

[14] Ibid., 157.

[15] Ibid., 160.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Cage, Silence, 10.

[19] Krauss, “The Originality of the Avant-Garde,” 161.

[20] Cage, Silence, 10.

[21] Ibid., 260.