The following article is republished from an earlier edition of The Journal for Cultural Theory. The link to the original article can be found here.

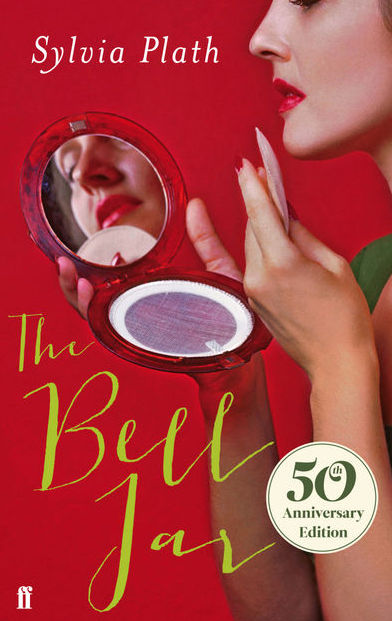

In early 2013, Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar was reissued by Farber and Farber in celebration of the book’s 50th anniversary. The shiny new cover features a striking red background with the profile of a white woman’s face and arms. She holds a compact mirror and is in the middle of applying powder to her chin.

What first strikes the potential reader are her lips, the same vibrant red of the cover, her nails painted with a matching red, and her eyes, lids lowered to the mirror, are visibly mascara-ed. And while the woman’s full face is not in view, as the cover cuts her off just above her eyelashes, the compact mirror reflects another vantage point: her lips full, the ditch of her philtrum, the darkness of her nostrils, her slender cheeks and partial eyelids.

Questions arise about the rhetorical purpose of the cover art: What is the main purpose of the image(s) that wrap the text? To draw readers? To hint at the book’s contents? To be a metaphor for the larger argument or purpose of the book? And, more specifically, what responsibility does the jacket designer have to visually represent the contents of the book? Is the responsibility of the jacket designer first to the publisher, by creating visual interest for a wide audience of possible consumers; or to the writer, by representing accurately the ideas that the book houses; or to the potential readers, by creating a reasonable expectation about what they will find in the book?

The Bell Jar controversial 50th anniversary cover from Faber and Faber. Dustin Kurtz’s, an independent book publisher, invective concerning the new Bell Jar cover. Popular media at the time responded negatively to The Bell Jar ’s new look. The online magazine Jezebel , whose tagline promises “Celebrity, Sex, Fashion for Women. Without Airbrushing,” characterized the cover as featuring a “low-rent retro wannabe pinup applying makeup.”1

Dustin Kurtz, an independent book publisher, tweeted “How is this [the new cover for The Bell Jar ] anything but a ‘fuck you’ to women everywhere?” Kurtz’s followers were quick to chime in about the seeming inaccuracy. The internet discussion became a spiraling web of redundantly linked ‘hear, hear!’s in which the cover was seen as shameful and disrespectful to Plath herself. The consensus appeared to be that books written by women about the complexities of womanhood should not be presented visually as “chick lit,” yet apparently it is a common practice of jacket designers to grossly misrepresent the contents of such books by doing just that.

The reissue of Plath’s The Bell Jar is just one more recent example of this fissure between the content of a book and the visual rhetoric of its cover. In the nearly countless editions of Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex, one finds similar dramatic tensions between covers and content. This germinal text in feminist philosophy developed a framework that several generations of critical theorists have used to examine the otherness of the female body and the disparity between men and women. In her critique of this social inequality, de Beauvoir focuses on the ways in which sexual difference has been key in the oppression of women.

Like the misguided jacket designer of Plath’s reissued The Bell Jar, the many designers of the Second Sex have worked primarily in three modes to represent the contents of this text: either they provide a photo of the author; they provide a text-only cover; or they offer a stylized image of a woman’s body, with clear will to objectivity, to the gaze of the viewer, and to the woman’s body as a thing of mystery and erotic desire.

The editions of the text that contain de Beauvoir’s image have two meaningful design themes. The first is that her image is in grayscale, while the text is in color and is ornate. The contrast is a striking study in emphasis and importance; her face in these cover designs creates a background for the title and is visually less compelling than the text itself.

For example, on the 1989 cover published by Vintage, de Beauvoir’s visage is unsmiling and blurred, her eyes gazing away from the viewer and her expression somewhat Mona Lisa-esque: possibly content, possibly annoyed. Her thin lips give little away. The text of the title and of the author’s name, however, have a distinct, almost playful personality. The capital S is highly stylized, the top of the letter curling over onto itself and the bottom of the letter appearing to be cut off. The capital E lacks vertical symmetry, with its middle arm floating substantially below the midline. Such lively font details create a contrast with the nearly style-less grayscale face.

The apparent rhetorical imbalance can be interpreted as responsible to the content of the book; indeed, the book is not about de Beauvoir specifically. That is, it is not a memoir of one woman, but instead a book about all women and their existence as always-situated against man and the patriarchy. And so while this particular design approach might initially appear disrespectful to the author, it may instead be interpreted as a function of de Beauvoir’s ethos as a philosopher, in the way we might place an image of Plato on the Phaedrus.

book is not about de Beauvoir specifically. That is, it is not a memoir of one woman, but instead a book about all women and their existence as always-situated against man and the patriarchy. And so while this particular design approach might initially appear disrespectful to the author, it may instead be interpreted as a function of de Beauvoir’s ethos as a philosopher, in the way we might place an image of Plato on the Phaedrus.

The text-only cover is, according to some designers, a mark of deference to the ideas in the book. J.D Salinger is rumored to have had some sort of clause in his publishing contract that prevented any images

from appearing on the covers of his books.2 It may have been the case with the several editions of de Beauvoir’s book that the jacket designers avoided misrepresentation, offense, or other missteps by using simple color and font face to mark the text, rather than attempt to create an image that could both compel readers and reflect the contents. As is the case with the Vintage first edition (May 3, 2011) of the most recent translation by Constance Borde and Sheila Malovany- Chevallier, the text-only cover still makes use of visual rhetoric, the word ‘second’ in the title blurred and pixelated. The metaphor used here is unmistakable: the implication is that women as ‘second’ to men is a fragile construction at best, a mirage of meaning that isn’t concrete or bound by anything essential or real.

So, the argument can be made that these two methods of graphical representation of de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex can fairly reflect the larger purpose of the book. The editions that contain an image of de Beauvoir carry the ethos of the author herself as a philosopher; the editions that offer a text-only front can still portray, rather handily, a sense of the book’s purpose. However, the final mode of representation—the portrait of a nude woman—creates a particularly problematic disconnect with the contents of the book itself. Two specific examples of this are from the 1961 Bantam paperback edition and the Foursquare edition with cover art by Edward Mortelmans.

Each of these editions contains a nude woman sitting on a bed, or what appears to be a bed, the folds of material on which they sit resembling blankets or bed sheets. In each image, the outline of the woman’s breast and nipple punctuates the landscape of her profile. In each, the woman’s hair falls in wild fashion: one blonde, one a fiery redhead. In each, the woman’s face is partially obscured by the vantage. Viewers get an ear in one, the crest of her nose in the other; both reveal a portion of an eyelid marked by the arch of an eyebrow.

The effect is arresting. To the viewer who has expectations for the text to be forward-thinking and revolutionary with regard to women and their bodies, the overtly sexualized woman-as- object on each cover will seem outrageously contradictory. These faceless bodies, offered up for the looker to gaze upon, are not the liberated beings in charge of their sexuality and of constructing their personhood that de Beauvoir’s book ought to inspire. Their bodies are positioned and offered up as near-cliché: soft, inviting, alone. Vulnerable, available, mysterious.

To the viewer who is unfamiliar with the text, these covers may create expectations that are likely to be unmet: the book does not contain pornography, does not contain romance nor a trite love story. In fact, readers will be met with what has been described as a “wrathful” rail against the disenfranchisement of women in the mid-20th Century, to include characterizations of intercourse as either violent violations or dull drudgery.3 No soft nakedness there.

As it turns out, readers have been miffed about the naked women on the covers of The Second Sex for decades. In “The Silencing of Simone de Beauvoir: Guess What’s Missing from The Second Sex,” Margaret A. Simons acknowledges facetiously that of course a naked woman would be on the cover of de Beauvoir’s book, “after all, this is a book about sex.”4 And a little bit of sleuthing reveals that the original translator of the book was a recruited to translate the text as a sex manual—Howard Parshley was an expert in reproduction, not philosophy or existentialism.5 So it may have been the convergence of misunderstanding and mislaid expectations that led to these grossly inaccurate book cover designs.

In another most recent edition of de Beauvoir’s work, the jacket designers may have been able to appease all three potential stakeholders in the cover art conversation: author, publisher, reader. The stark, matte black background is overlaid with the simple image of a Victorian underbust-style corset, the shape-forcing device curving harshly in at the waist. The rigid busks and grommets wait for a body to re-form.

The corset is arguably the ultimate metaphor for the ways in which women’s bodies have been expected to conform—nearly always unreasonably—to a version of woman constructed by society. The iconic image of the corset comes from Gone with the Wind of Scarlett O’Hara yelling at her maid, Mammy, to torque down her corset more tightly to achieve a specifically (and horrifyingly) small (17 inch) waist. Women were known to faint and damage their internal organs for the sake of literally ‘fitting in’ to a particular shape. The image of the corset delivers quite effectively the notion that this book is about women and their conflicted existence: to be asked to be someone else than they might otherwise be, simply based on those expectations laid upon them by men (and ultimately other women).

To control the body, to civilize it, to make it satisfactory for public consumption, to reign it in, to restrain it, contain it. This jacket, with the corset empty of a woman’s body, illustrates that we can observe the structures of society and culture that would hold women in. Women can step out of the metaphorical corset of the patriarchy and examine it. The design of this cover will be, perhaps, compelling to buyers, which will appeal to the publisher; clearly represents (if figuratively, broadly) the purpose of the book, which respects the author; and it complements the text, which supports readers’ understanding.

To control the body, to civilize it, to make it satisfactory for public consumption, to reign it in, to restrain it, contain it. This jacket, with the corset empty of a woman’s body, illustrates that we can observe the structures of society and culture that would hold women in. Women can step out of the metaphorical corset of the patriarchy and examine it. The design of this cover will be, perhaps, compelling to buyers, which will appeal to the publisher; clearly represents (if figuratively, broadly) the purpose of the book, which respects the author; and it complements the text, which supports readers’ understanding.

What this Vintage edition of The Second Sex shows, then, is that the questions posed at the beginning of this brief survey might be moot: visually, the jacket design can indeed be expected to serve several masters in the marketplace of books. There isn’t any need to determine priority; rhetorically effective cover design is nimble and lithe.

Madeline Yonker earned her PhD in Composition and Cultural Rhetoric from Syracuse University. Currently she is an assistant professor of Composition and Rhetoric at York College of Pennsylvania. Broadly, her research and teaching interests include technorhetoric, professional writing and tech comm, digital culture, networks, narrativity, and composition-as-social.

_________________________________________________________________________

1 Morrisey, Tracy Egan. “’The Bell Jar’ Gets a Hideous Makeover.” Jezebel. 1/23/13 http://jezebel.com/5978457/the-bell-jar-gets-a-hideous-makeover/

2 Pieratt, Ben. “Salinger’s Design Clause.” The Book Cover Archive Blog. 1/25/2009 http://blog.bookcoverarchive.com/2009/01/407/

3 du Plessix Gray, Francine. “Dispatches from the Other.” Sunday Book Review: The New York Times. 5/27/10 http://www.nytimes.com/2010/05/30/books/review/Gray- t.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0

4 Simons, Margaret A. “The Silencing of Simone de Beauvoir: Guess What’s Missing from The Second Sex.” Beauvoir and the Second Sex: Feminisim, Race and the Origins of Existentialism. (1983)

5 Ibid.