Fitzgerald, Francis. The Evangelicals: The Struggle to Shape America. New York City, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2017. ISBN-10: 1439131333. Hardcover. 637 pages.

In her book The Evangelicals: The Struggle to Shape America, historian and Pulitzer Prize winner Francis Fitzgerald provides a comprehensive history of white evangelical movements in America for the express purpose of explaining the formation of the Christian right and its modern evangelical opponents. Fitzgerald takes readers on a 637 page journey from the Great Awakenings of the 1700’s to the 2016 presidential elections, highlighting themes such as the effects of the North-South divide, fundamentalism, race, and Christian celebrity. Demonstrating her journalistic roots, Fitzgerald presents an even-handed and historically accurate portrayal of the development of evangelicalism in America that neither maligns nor lauds the culture, but instead contents itself to explain how part of the largely decentralized evangelical movement solidified into what has come to be known as the Christian right, and how it rose and subsequently fell from power.

As amazing as The Evangelicals is, finding an explicit thesis statement in Fitzgerald’s book is slightly problematic. She makes many pithy statements, and offers an innumerable amount of insightful comments on the history of the Evangelical movement, but seems to present no formal argument. If I were to try and cobble together a thesis for the book it would be something akin to the following: “The Evangelical movement which began during the First Great Awakening and grew into an empire during the Second Great Awakening attempted to preserve it’s orthodoxy through Bible societies which played stage for great conflict between fundamentalists and modernists during a lull of evangelical vigor until it was reinvigorated after WW2 with the upsurge of fundamentalism and with the emphatic urging that conservative Christians enter politics to save the nation.

It was at this point that R. J. Rushdoony and Francis Schaeffer spearheaded the formation of the Christian right, which would dwindle during the Clinton administration but find its resurgence with the presidency of George W. Bush, developing into “new evangelicals” and subsequently declining after the bad press of the second Bush term until it elected Donald Trump in the 2016 election, despite no longer dominating evangelical discourse.” There seems to be no concise way to explain the crux of Fitzgerald’s book, but it is certainly worth the read nonetheless. Never has such a complete and deeply researched history of the movement been compiled.

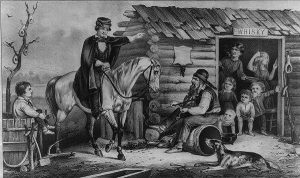

Though the book has an enormous amount to offer, Fitzgerald’s tracing of race relations in the Southern Baptist Church  stood out as particularly compelling. She explains that the issue of slavery caused the formal divide between Baptists and Methodists, as northern and southern evangelicalism developed differently. The North and Methodist ministers alike highly discouraged slavery and urged strongly for their congregations to emancipate their slaves. In the South, Baptists and Presbyterians simply urged for a kinder treatment of slaves. What originally was a cultural difference developed into a doctrinal difference as the anti-slavery movement grew in the North. According to Fitzgerald, the South began to argue for slavery as a Biblical practice, which took it from something southern evangelicals considered morally neutral to a moral good. The problems this wrought can be seen and felt in the SBC to this day.

stood out as particularly compelling. She explains that the issue of slavery caused the formal divide between Baptists and Methodists, as northern and southern evangelicalism developed differently. The North and Methodist ministers alike highly discouraged slavery and urged strongly for their congregations to emancipate their slaves. In the South, Baptists and Presbyterians simply urged for a kinder treatment of slaves. What originally was a cultural difference developed into a doctrinal difference as the anti-slavery movement grew in the North. According to Fitzgerald, the South began to argue for slavery as a Biblical practice, which took it from something southern evangelicals considered morally neutral to a moral good. The problems this wrought can be seen and felt in the SBC to this day.

Fitzgerald manages to compile and navigate the nebulous complexities of American evangelicalism with authority and grace. Fitzgerald states:

Evangelicalism today includes any Christians traditional enough to affirm the basic beliefs of the old nineteenth-century evangelical consensus: the Reformation doctrine of the final authority of the Bible, the real historical character of God’s saving work recorded in scripture, salvation to eternal life based on the redemptive work of Christ, the importance of evangelism and missions, and the importance of a spiritually transformed life and in doing so gives name and form to the movement.

This book is a boon to any individual seeking to better understand the religious underpinnings of the American political climate, be that for personal edification or teaching – secular or religious.

Rebekah Gordon is a graduate in the Religious Studies department at the University of Denver. She is an editor for the e-mag Esthesis as well book editor for The Journal for Cultural and Religious Theory.