The following is the first installment of a two-part series.

In 1895, when Myrtle Fillmore, co-founder of the Unity School of Christianity, first became a vegetarian, she said that “the appetite left me without my even thinking about it and I am sure I outgrew the demand for murdered things” (37). One realizes upon hearing this that the move to murder-free eating involved a conversion of some sort, one that she saw as religious.

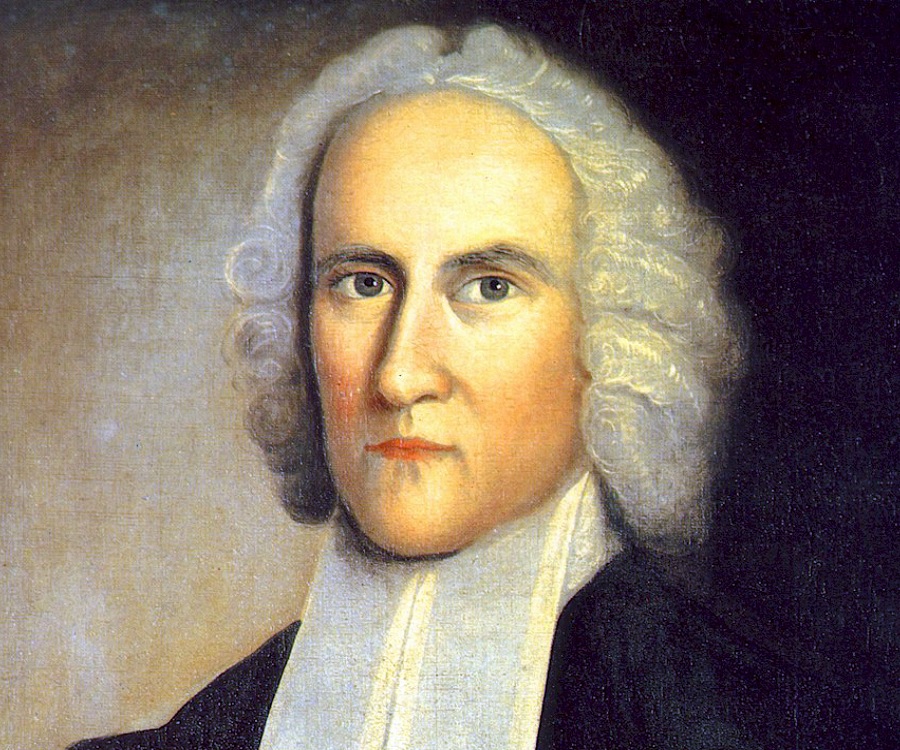

Conversion has a noteworthy place in American religious history. The Great Awakening of 1730s colonial America saw a promulgation of conversion experiences both encouraged and regulated by Puritan clergy. Most famously, the philosopher Jonathan Edwards was most prominent among those who set out to regulated the experience, coming up with criteria for distinguishing true workings of God from the superficial symptoms.

What follows is an attempt to use Edwards, along with ideas of conversion, in a surprising place, namely the morality of eating animals. It is not strange to speak of becoming vegetarian or vegan as involving something like a religious conversion. But what if this conversion were pre-ordained, as it would be in Calvinism? My contention is that adopting an Edwardsean perspective on vegetarianism — talking about the existence of a vegan elect -helps to explain why it is that among those who accept the persuasive arguments for veganism, some people find it easy to become vegetarian or vegan, and others find it difficult.

From the point of view of certain religious minds, it seems like some are preordained to follow the gospel of nonviolence that leads to rejecting flesh as food, while others are not. Whether God exists, and further is Christian, and further has preordained that some will be saved, is one matter. But even without taking a position on those matters, we can use Edwards’ ideas to explain veganism as a conversion experience involving certain important psychological factors.

To explain, we need to present an overview of Edwards’ ideas of conversion and salvation, with particular attention to the possibility of making a distinction between the discovery or sign of grace, and the development of signs of grace. Exploiting any ambiguity we find in Edwards, we can show that grace is something that it said to be discovered, but which is really developed. This pragmatic approach to theology, heretical if expressed outwardly in Edwards’ America, is nonetheless an interesting implication of Edwards’ philosophical theology.

Signs of Election

The doctrine of predestination is logically and psychologically complex, but it is founded on a basic idea that God is all powerful, and thus that humanity is completely depraved, that is, completely lacking in power to do good. This lack of power, however, cannot be more than theoretical, since any human being questioning whether they have been chosen among the saved is sure to try to prove it.

God has it determined, indeed, but God has, so to speak, certain tells, that is, indirect evidence of God’s will. These signs of election are, in principle, merely discovered, but in practice, they can be developed. To mollify the anxiety of not knowing if one is saved, one can look really hard for signs, which, practically speaking, amounts to the development of a certain practices. When you develop something, you contribute something of yourself to the process of bringing it out.

This is particularly evident if one considers the idea of enduring a trial. If a sign of grace is having the fortitude to survive a strong temptation, it seems to be relatively unimportant where the source of the will is, just so long as someone makes it endure. Edwards’ Treatise Concerning Religious Affections begins with a exegesis of a section from 1 Peter that Edwards says “speaks of the trial of their faith,” which are done “through manifold temptations” (13) for the Christian.

One type of trial is gustatory. Elmer Towns from Liberty University, for example, promulgates The Daniel Fast for Spiritual Breakthrough. Based on consideration from passages in the Book of Daniel, the fast is “an expression of abstinence for purposes of self-discipline” that requires “you give up the things you enjoy eating and eat only what is necessary” (20). Although acknowledging that his belief stops short of full Biblical authority, he nonetheless maintains a personal belief that this fast is required of Christians.

The Daniel Fast is not primarily a dietary choice; it is a spiritual vow to God. You may lose weight during your fast, or you may lower your blood pressure or cholesterol, and while these results are good, they are not the primary focus of the fast. Instead, you are fasting for a spiritual focus. Improved health is always a secondary result … (21).

Remarkable here is Towns’ belief that the fast is not just a choice. For him, it is not part of a lifestyle option, but has what he takes to be real results: Christian spirituality. Christian spirituality is itself not just a choice according to evangelicals, and so Towns says that the Daniel Fast is a “lifestyle vow” (24).

Daniel and other especially fit Israelites were selected by Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar for special training in his palace, which included “a daily amount of food and wine from the king’s table” (1:5), and Daniel did not want to “defile” himself (8). Jewish dietary laws were cultural, but the story’s focus quickly turns to health. When a sympathetic guard agrees to give Daniel and four other Jews only vegetables and water (12) rather than the considerably more luxurious wine and flesh, the men after 10 days looked “healthier and better nourished” (15) than the non-Jews.

The point seems to be that the war-culture Babylonians, who did not care about Jewish cultural quirks, did care about vim and vigor. But more importantly to the Jew or Christian, the effects were that to the men “God gave knowledge and understanding of all kinds of literature and learning” with Daniel specifically given the ability to “understand visions and dreams of all kinds” (1:17). The fast provided a means to display Daniel’s God-given abilities.

It would be mistaken to think that Daniel’s request for abstinence was simply a matter of cultural distinction. It was not just like a contemporary teenager who wants to have piercings as a mark of some kind of continually burgeoning piercing subculture. It is permissible to see Daniel’s abstinence, although apparently presented respectfully, as making a statement against the specifics of Babylonian culture. Daniel is showing that strength comes from humility and intelligence, not from the ingestion of meat, sacrificed to gods in the promotion of death for the greater good, and not from acceptance of the drunken fruits of noble war-culture.

It is not difficult to see an antiwar, antiviolence statement in this story, one that extends even into food choices. Towns does not see this, and in fact makes the following statement, which is unintentionally disclosive: “When you begin a Daniel Fast,” you purify the body and “repent of sin (probably not the sin of eating meat, but other sins associated with the flesh) and are drawn closer to God through the experience” (22). Towns likely meant that eating meat is not a sin, but syntax betrays him.

Theologian Stephen Webb calls this story “the first clinical study of nutrition” (20), but it is also more than a clinical trial. Edwards refers in his Treatise to trials “as apparent gold is tried in the fire, and manifested, whether it be true gold or not” (13). The results of this are a joy that is “unspeakable,” “very different from worldly joys and carnal delights,” and given to people “in their state of persecution” (15). Edwards is not of course using “carnal” in the same sense that one would in a gustatory context.

Nevertheless, the connection between general spiritual carnality and specific gustatory carnality can be made. The rejection of gustatory carnality is importantly similar to what Edwards talks about when referring to the ineffable sweetness of grace. This grace, he says, is given to the elect. Although many can enjoy the general graces of God, only a few can appreciate the special sweetness. The vegan elect are a contemporary example of the Christian elect of which Edwards was speaking.

Great Awakenings: A Taste for Goodness

Writing in relation to the Great Awakening, in which emotions were running high, Edwards begins by explaining that a number of common phenomena are neither necessary nor sufficient conditions for being saved. For example, Edwards says that “it is no sign one way or the other that religious affections are very great, or raised very high” (50). Edwards on the one hand is arguing against religious rationalists who believe that religious affections disqualify truthful apprehension of the divine.

On the other hand, he is ensuring that such affections are not seen as a mark in themselves of grace. Edwards refers to passages about unspeakable joy, and loving God with your whole heart, soul, mind and strength. The Psalms speak of crying rivers because of the world’s disobedience, and having flesh that “longeth for thee in a dry and thirsty land” (Ps. 63:1). Finding God and righteousness, “my soul shall be satisfied, as with marrow and fatness” (5). Edwards adds that “because high degrees of joy are the proper and genuine fruits of the gospel of Christ, therefore the angel calls this gospel ‘good tidings of great joy that should be to all people’” (53).

It is apparent that many who try a vegetarian diet feel much better afterward, and it would not be surprising to find someone feeling very happy about it, going from a state of unsatisfied eating to one in which they are joyful. They may gain or lose weight in way that makes them feel better about their body, both in terms of health and appearance. They may see the wrongness of eating flesh, and cry for the animals affected by the meat culture around them.

All of this, however, does not always last. As Edwards notes about the great awakenings around him, the great affections might be signs of grace, but they might not as well, and thus are not reliable guides. The Jewish people around Mount Sinai earnestly proclaimed fidelity to God’s covenant, but when Moses left, Edwards notes “how quickly were they turned aside after other gods, rejoicing and shouting around their golden calf” (54–55). And exalted by Jesus raising Lazarus from the dead, says Edwards, the people raised up Jesus with cries of “Hosanna!” turning into “Crucify!” (55). With vegetarian converts, the righteous deliverance can be followed by relapses in which they find themselves around the Golden Calf, or, more precisely, under the Golden Arches, satisfying a fast-food craving.

Edwards also argues that “It is no sign that affections have the nature of true religion, or that they have not, that they have great effects on the body.” He speaks in reference to notions of psychosomatic unity according to which “the mind can have no lively or vigorous exercise without some effect upon the body” (55). Among others, he quotes Habakkuk, who he says was “overbourne by a sense of the majesty of God,” (58) causing the prophet to note that “my belly trembled; my lips quivered at the voice: rottenness entered into my bones, and I trembled in myself” (Habakkuk 3:16).

There is a mixture of literal and figurative language here, but the sense is that true affections can be associated with feelings in and about the body. Yet the presence of a trembling belly does not necessarily indicate the presence of God any more than a rumbling stomach indicates real hunger. Nor do quivering lips indicate true fear of God.

What is more, the peculiar lip movements associated with speech are not reliable signs of conversion: We cannot tell anything from people who are “fluent, fervent, and abundant, in talking of the things of religion” (59). Speaking of things that happen even today, in religion and elsewhere, Edwards says that

A person may be over-full of talk of his own experiences; commonly falling upon it, every where, and in all companies, and when it is so, it is rather a dark sign that a good one. As a tree, that is over full of leaves, seldom bears much fruit; and as a cloud, though to appearance very pregnant and full of water, if it brings with it over-much wind, seldom affords much rain to the dry and thirsty earth: which very thing the Holy Spirit is pleased several times to make use of, to represent a great show of religion with the mouth, without answerable fruit in the life. (61)

Some vegetarians do indeed become like evangelists, preaching and and trying to convert rather than accept others’ settled beliefs. The example of the over-burdened tree is significant in a number of ways. Not all words are nutritious in the way that not all food is nutritious. In fact, an over-abundance, even of even healthy food is not a guarantee of health. The idea here is none other than the old philosophical advocacy, made most notably by Aristotle, of fitness and proportionality. In addition, although it was likely not intended, the example of a tree and the thirsty earth suggests the significance of fruit and water, as opposed, perhaps, to flesh-food, which is indeed filled with water, but not with health.

As is characteristic of the Treatise, Edwards takes an approach where he rejects certainty on both sides. Among the other supposed signs Edwards notes, there is that of a feeling that things are coming not from “their own contrivance” or “by their own strength” (62). He uses this as an opportunity to critique overly rationalist theologians.

How greatly has the doctrine of the inward experience, or sensible perceiving of the immediate power and operation of the Spirit of God, been reproached and ridiculed by many of late? They say the manner of the spirit of God is to co-operate in a silent, secret, and undiscernible way with the use of means and our own endeavors; so that there is no distinguishing, by sense, between the influences of the Spirit of God, and the natural operations of the faculties of our own minds. (63-63)

For Edwards, it is not that God cannot be subtle; it’s just that God does not have to be subtle. Edwards is allowing both that God can manifest in a way that seems overpowering to the will, and also in ways that seems indistinguishable from one’s normal will. The source of the change is inaccessible to others, and even to ourselves; we can only judge conversions by the appropriateness of the effects.

Religious pragmatist William James would later read the Treatise and conclude that “the roots of a man’s virtue are inaccessible to us. No appearances whatever are infallible proofs of grace. Our practice is the only sure evidence, even to ourselves, that we are genuinely Christians” (24). The “even to ourselves” part, present in the writings of both Edwards and James, might be somewhat startling to hear. It is a critique of the idea that humans have complete clarity about intentions. Yet matters of intentions usually appear complicated upon the narrowing of introspection, and are invisible at the point of origin.

Tadd Ruetenik is Professor of Philosophy at St. Ambrose University in Davenport, Iowa. He is the author of The Demons of William James: Religious Pragmatism Explores Unusual Mental States (Palgrave Macmillan, 2018).