To speak or not to speak of God is an important yet rather uncomfortable question that participants encounter during interreligious and interdisciplinary dialogue. Several Eastern religions, philosophers, and scientists claim God is either non–existent, absent, or “dead” in relation to the cosmos. Conversely, other faiths believe God’s absolute presence embraces everything.

For Abrahamic traditions, God indeed is present to the universe yet the divine also is transcendent; the Creator is wholly other than creation. Nevertheless, divine otherness epistemologically implies that the Creator is absent and unknowable to creation. Discussions about God’s presence and absence likewise become complicated because imperfect human language is incapable of explaining God’s ontological distinction. Apophatic theology recognizes humanity’s reasoning and language limits in the struggle to articulate divine incomprehensibility.

Conversely, the kataphatic approach utilizes religious analogical imagination to communicate God’s presence in the world. Both approaches employ contrastive techniques, which prove inadequate when discussing the dichotomy of divine presence and absence. Instead, the notion of non–contrastive transcendence is a more effective approach to speak of God.

The act of creation involves an explicit ontological distinction; God creates beings, while God is being, itself. In what Robert Sokolowski calls the Christian distinction, “God is understood as ‘being’ God entirely apart from any relation of otherness to the world or to the whole. God could and would be God even if there were no world.”[1] Hence God creates, not from necessity but from a spontaneous originating freedom as the essence of being or existence. Christian distinction thus establishes a “special sense of otherness between God and the world”[2] that qualifies an asymmetrical relationship. The Creator depends on nothing yet creation is completely contingent upon its Creator.

In addition to being distinct from the cosmos, God is prior to distinction per se. Nevertheless, God permits distinction even though the world does not have to exist nor does God have to be distinguished from it.[3] Distinction theologically preserves divine free will along with the gratuity of grace and the meaning of salvation. Emphasizing dissimilarity likewise avoids inaccurate views of Creator/creation relations, associations with imperfection and suffering as well as misleading perceptions of evil as God’s ontological equal. In sum, Christian distinction describes God as totally dissimilar, unequalled, and thus completely other, the Creator who surpasses a radically contingent creation.

The notion of Christian distinction facilitates a spectrum of possible scenarios describing the Creator’s interaction with creation. Within atheism, the non–existence of God logically implies no divine presence. Influenced by the Enlightenment, deism claims that God created the world to operate according to natural laws without divine direction or presence. Pantheism theologically views God and the cosmos as equivalent; therefore, God’s presence is constant and absolute.

According to panentheism, the Creator maintains an intense presence within creation, however, some distinction exists. Classical theism promotes a more discrete Creator/creation distinction than panentheism; the infinite God is present yet distinct from and unaffected by the finite world. An essential ontological distinction between the Creator and creation determines as well as preserves unique identities. Separate identities construct otherness, a crucial component for relationships.

However, an overemphasis on distinction suggests dualism along with the aloofness of deism. Avoiding dualisms that equate goodness with spiritual matters and evil with material things necessitates divine immanence along with divine transcendence to maintain a theological balance within the Creator/creation relationship.

Although distinct, the wholly other Creator freely enters into a loving relationship with creation. These notions of relation and wholly otherness parallel the theological terms of divine immanence and transcendence, respectively. For Augustine and Aquinas, God’s immanence expresses nearness, a close presence in the world. Augustine claims that God is “more intimately present to me than my innermost being, and higher than the highest peak of my spirit.”[4] Similarly, Aquinas describes God’s immanence as intimate, an innermost presence in all things[5] at all times. All of creation continuously experiences divine goodness and presence, which sustains and guides it toward its ultimate purpose.

God’s transcendence, in some ways, enhances an understanding of divine immanence. Transcendence refers to the Creator’s absolute otherness, a radical differentiation that is incomprehensible to mere creatures; thus, to humanity, God appears to be hidden or absent. Augustine describes the experience of divine absence as spiritual longing for God’s presence by writing, “You have made us for yourself, and our heart is restless until it rests in you.”[6]

Yet through the perceived hiddenness or absence of transcendence, “God shows himself [sic] not to be among the things of our world. He is disclosed in his absence,”[7] paradoxically, as a unique type of close presence or divine immanence. God’s presence varies in intensity as a “continuum moving from general or creational presence to theophanic presence.”[8] Transcendence also may be a “particular form of absence called ‘vagueness,’”[9] a veil through which clarity emerges as God discloses Godself in an interplay of presence and absence according to God’s plan. Consequently, God is free to be present or absent and to communicate with others of God’s choosing. Any other condition limits divine transcendence.

Transcendence also facilitates creation’s unique being and freedom, but exposes the world’s fragility and total dependence on God. Hence, divine immanence and transcendence coexist in tension, “an extreme of divine involvement requires, one could say, an extreme of divine transcendence.”[10] God’s presence maintains the world’s existence while divine absence enables human free choice. When creatures refuse to acknowledge their complete dependence on the Creator, they misinterpret divine transcendence, omnipotence, and benevolent immanence.

Divine immanence and transcendence both contribute to divine mystery. According to Catherine Mowry LaCugna, “to speak of God as mystery is another way of saying that God is ‘personal’”[11] and present; in other words, “God is for us”[12] and with us, even at difficult times when God seems absent. God initiates spiritually intimate encounters with humanity through grace.

At the heart of human existence is the “free, unmerited and forgiving, and absolute self–communication of God,”[13] known as grace. The gift of grace connects the distant transcendent aspect of divine mystery by offering God’s own being, in a personal, close immanence to humanity. The immediacy of God’s presence occurs as a gratuitous invitation to faith, which humans freely may reject or accept. Found in most religious traditions, faith is the “fundamental acknowledgement of creatureliness [sic] in the face of whatever one takes to be the transcendent.”[14] The religious experience of divine immanence establishes and cultivates the Creator/creation relationship, while the transcendent aspect of God retains a sense of wonder or awe.

Additionally, the Incarnation of Jesus Christ provides the appropriate immanence necessary for humanity to experience and respond to divine transcendence. The event places God and humanity in solidarity, in an inseparable, affective unity of love along with an ethical and ontological relation.[15] Through this asymmetrical, but real and loving relation, the Creator is present to creatures in communion with Christ and the Holy Spirit.

Sokolowski posits that the dichotomy of absence and presence establishes the conditions for the possibility of divine Incarnation; it destroys neither the divinity nor humanity of Jesus Christ. As a finite creature, the infinite Creator actually is present “yet his [sic] presence can go undetected since, despite his proximity, his divinity is hidden, veiled, absent.”[16] Consequently, humanity’s personal encounter with God through the Incarnation exemplifies God’s presence in a phenomenologically unique way.

Theological and philosophical discussions about divine presence imply the necessity of absence. Contrasting immanence and transcendence, while appropriate, is inadequate when speaking of God, who encompasses both attributes.[17] Nevertheless, human reason constructs understanding through contrasts, opposites, and negation. Contrastive methods compare God as one being among others within a single order.[18]

This approach suggests the divine and non–divine coexist side–by–side, which infers that “God is as finite as the non–divine beings with which it [sic] is directly contrasted.”[19] Contrastive transcendence ironically limits God to what is opposed to God. While too much contrast objectifies God as a created thing, emphasizing excessive similarities between God and creation nullify the Christian distinction. Defining the Creator’s transcendence over and against the world often results in a complete disassociation with creation; as divine transcendence becomes more absolute, God appears increasingly absent from the world.

Due to the Creator’s radical transcendence, creatures are epistemologically incapable of truly knowing God. Attempts at a comprehensive, intelligible description of the infinite exceed the finite limits of human language and reason; therefore, theologians employ apophatic theology to speak of God. As a contrastive method, apophatic theology acknowledges the wholly other Creator is completely unfathomable to creation.

Hence, this via negativa approach articulates only what cannot be attributed to an ineffable God. Tertullian explains “that which is infinite is known only to itself… He [sic] is presented to our minds in His transcendent greatness, as at once known and unknown”[20] or equivalently at once present and absent. In fact, God’s transcendence is the only definitive knowledge scholars possess about God because God surpasses any humanly conceivable attributes. To avoid agnosticism or skepticism, theologians employ nuanced language that expresses theological uncertainty rather than deny faith.[21] Apophatic theology also prevents anthropomorphizing God even as it reinforces divine mystery.

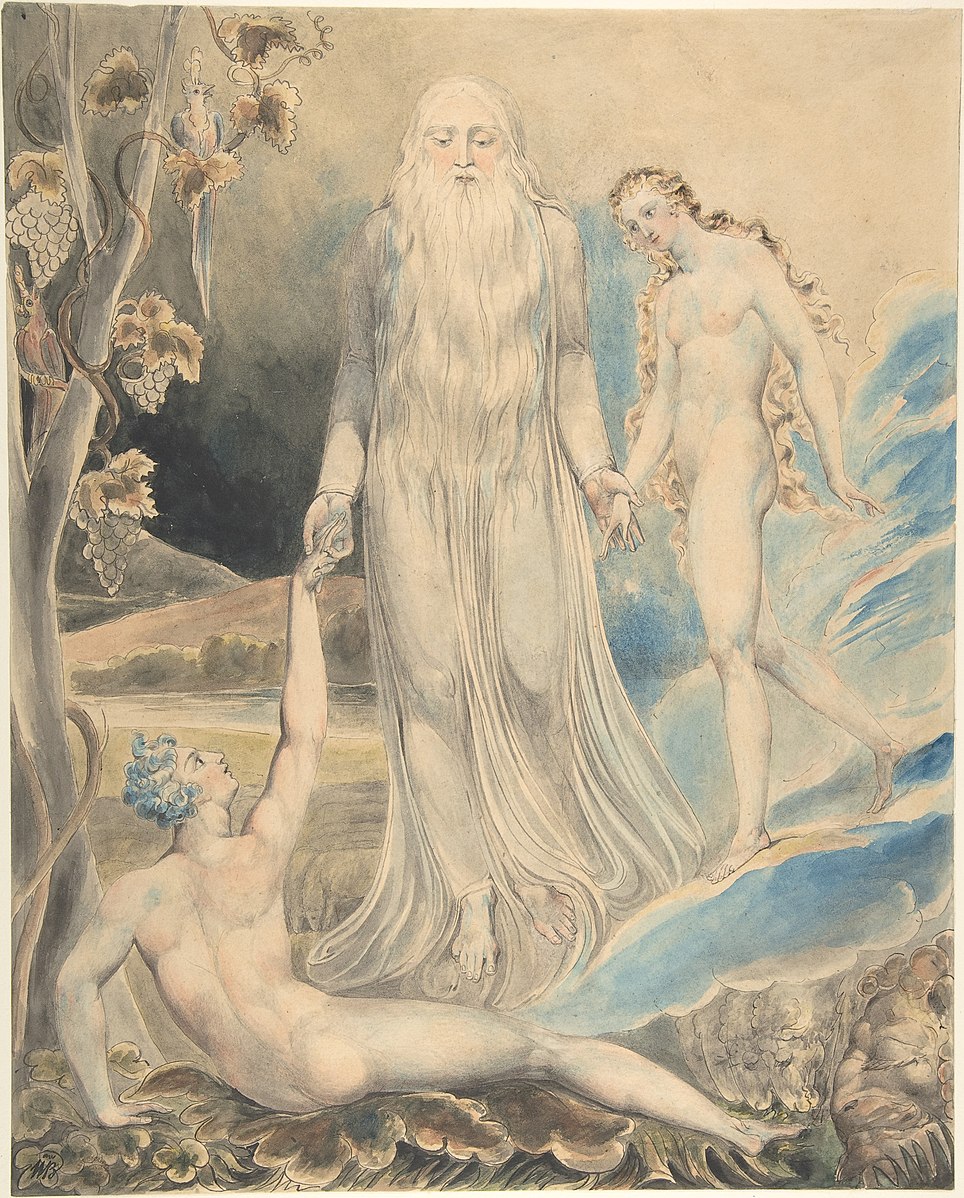

Whereas apophatic theology emphasizes God’s absence, kataphatic theology positively expresses divine immanence. The Creator’s revealed presence frequently manifests in creation and human history. St. Bonaventure imagines “the created world is a kind of book reflecting, representing, and describing its Maker.”[22] Consequently, creation is the constant process of revealing and glorifying God. Sacred Scriptures likewise narrate God’s presence and interaction in salvation history through covenantal promises, theophany stories that disclose the glory of Jesus Christ as the Incarnate Word, and with accounts of how the Holy Spirit reveals the Creator’s presence via spiritual encounters that invite creatures to participate in God’s divine plan.

Creating humans in the image of God (imago Dei) is another significant way God’s presence manifests in others to disclose divine immanence and mystery. As the basis for human dignity and rights, the imago Dei is a significant component of biblical revelation involving divine presence. Augustine emphasizes communal aspects of a Trinitarian imago Dei that associates human creatures with the Creator, while Aquinas believes the imago Dei encourages humanity’s participation with divine presence through intellectual contemplation.[23] When Christians imitate Christ’s life and participate in the paschal mystery, they reconfigure humanity’s imago Dei into the image of Christ (imago Christi), whom Christians believe is the most perfect imago Dei for revealing God (Jn 14:9) and God’s presence in the world.

Kataphatic approaches contrast humanity’s limited knowledge about God with divine encounters through appropriate language grammars and theological analogies. Language brings the abstract ambiguous absence of God into a more concrete language–sign of presence, communication, and revelation.[24] Kataphatic theology expresses God’s revealed attributes, such as goodness, justice, or love, relative to a divine perfection that surpasses human understanding and capabilities. Otherwise, kataphatic theology arrogantly presumes complete knowledge of God, which idolatrously anthropomorphizes God in humanity’s image.

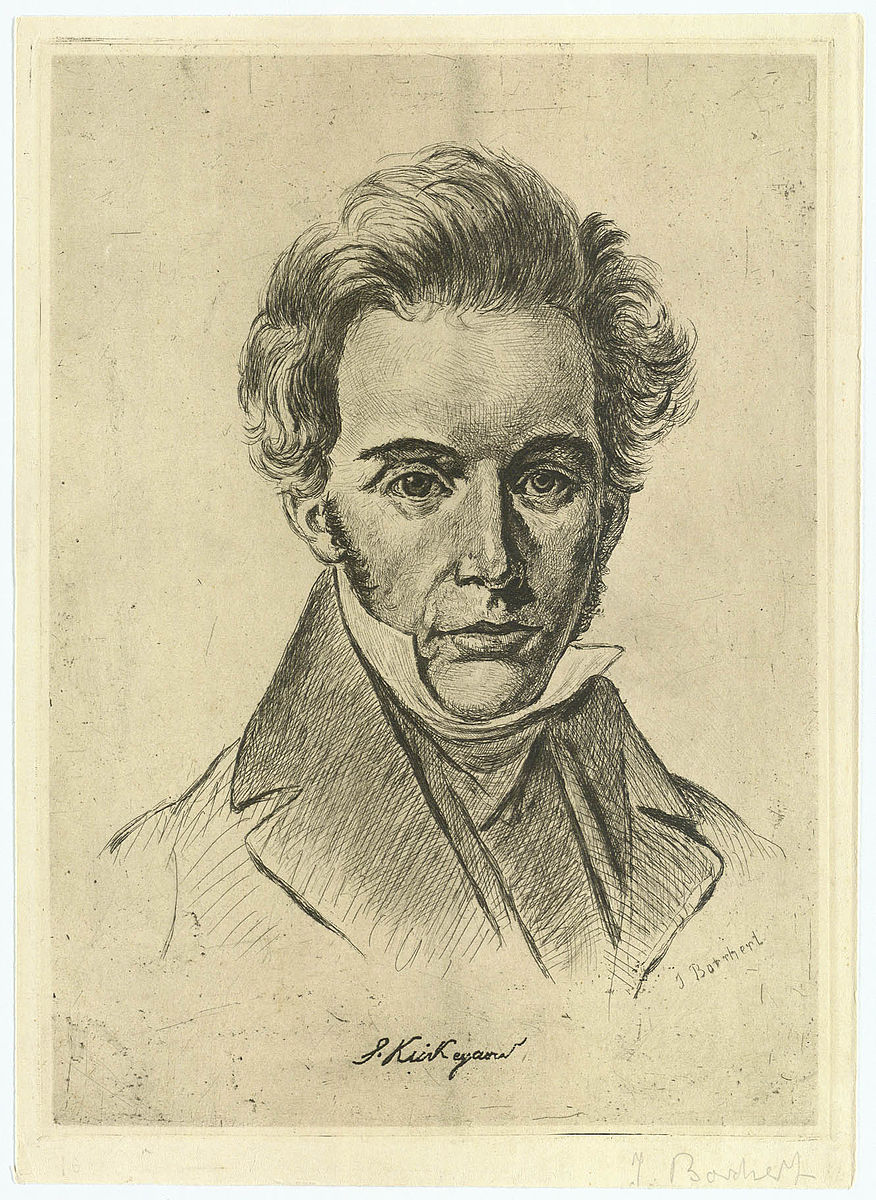

Therefore, an appropriate balance of kataphatic and apophatic theology is necessary to express what is known and mysterious about God by articulating notions of absence and presence. Nevertheless, divine immanence and transcendence “exceed all oppositional contrasts characteristic of the relations among finite beings”[25] and infinite being. While direct contrasts between creatures are epistemologically logical, they are “not radical enough to allow a direct creative involvement of God with the world in its entirety.”[26] Speaking of God who transcends the world requires what Kathryn Tanner describes as non–contrastive or noncompetitive transcendence.

With non–contrastive transcendence, God and the world are not opposed to each other nor are they parallel to each other. The Creator is not equal with creation. Non–contrastive transcendence upholds the Christian distinction between the Creator and creation but not through their differences, because “God is neither like the world nor simply unlike it… God is beyond the difference between like and unlike, beyond simple identifications or simple contrasts.

That is just what makes God different from anything else.”[27] Contrastive transcendence is therefore an inadequate comparison since “a God who transcends the world must also… transcend the distinctions by contrast appropriate there.”[28] Conversely, a radical non–contrastive approach respects God as wholly other, yet permits God’s immanent creative activity and involvement with the cosmos without placing both in competition.

To speak of God in diametrical terms of absence and presence is an exercise of contrastive transcendence. From a non–contrastive viewpoint, God is “necessarily hidden and yet somehow pervasive in the world,”[29] not in spatial terms but in a theological sense of the Creator’s existence and love for creation. If God surpasses all contrasts with the world, then the transcendent Creator must be immanently present to creation in God’s radical distinction, which prevents compromising the divine nature. Otherwise, any Creator–creature relationship diminishes divine transcendence and implies God is finite.

Without God’s presence or influence in the world, the Creator is merely an absent observer while creatures freely dictate the world’s resultant development. However, total divine presence and control implies responsibility for evil even as it nullifies human free will. These two options assume that creaturely free will requires absolute autonomy from the Creator and portrays Creator and creature freedom as a zero–sum game. Rather than directly contrasting freedoms, non–contrastive transcendence enables both divine and human free will to operate in tandem to effect creation, albeit in completely distinct but related ways.

When discussing divine transcendence in the context of God’s absence and presence, Tanner recommends two linguistic rules. The first rule is to avoid comparing God’s transcendence either as univocal or as a rudimentary contrast between divine and non–divine attributes similar to the ancient pagans; the second rule is to define God’s creative agency as immediate and completely extensive rather than restrict or limit it.[30]

Utilizing her rules, Tanner likewise appropriates Aquinas’ metaphysics that describe God’s nature as “ipsum esse subsistens”[31] (subsistent being itself). In other words, divine essence and existence are identical, which prevents onto–theology from considering the being of both the Creator and creation as equivalent. Thus, God’s absolute ontological otherness prevents relative contrasts or comparisons between Creator and creation.

To speak of God’s presence and absence involves relation and distinction. Christian distinction employs the divine attribute of transcendence to constitute radical difference between God and the world. As wholly other than creation, the Creator seems to be hidden or absent from human understanding. Yet Christian distinction also articulates how God freely chooses to create, rather than from necessity. Through divine immanence, the Creator establishes and cultivates the Creator/creature relationship, while sustaining and guiding creation to its perfection. Apophatic and kataphatic theologies emphasize God’s transcendence and immanence, respectively.

These approaches contrast divine attributes with human perceptions of God. However, God’s absolute transcendence essentially means direct comparison through contrast is illogical if not impossible. Non-contrastive transcendence recognizes that the Creator is being itself; wholly other and beyond comparison with created beings. By preserving the proper relationship between the infinite and the finite; God is immanent and active in the world without diminishing divine transcendence.

Joyce Konigsburg is Visiting Assistant Professor of Religious Studies at Notre Dame of Maryland University.

________________________________________________________________

[1] Robert Sokolowski, The God of Faith and Reason: Foundations of Christian Theology (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 1995), 32–3.

[2] Ibid., 33.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Augustine of Hippo, Confessions, III 6.11. See also Augustine, De Trinitate, VI 8.

[5] Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, <http://www.basilica.org/pages/ebooks/St.%20Thomas%20Aquinas–Summa%20Theologica.pdf> (accessed January 30, 2016), I Q8.1, 2; I Q4.3, 4.

[6] Augustine, Confessions, I 1.1.

[7] Allen Vigneron, “The Christian Mystery and the Presence and Absence of God,” in The Truthful and the Good: In Honor of Robert Sokolowski, eds. John J. Drummond and James G. Hart (Boston MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1996), 186. See also Robert Sokolowski, Eucharistic Presence: A Study in the Theology of Disclosure (Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press, 1994), 195.

[8] Terence Fretheim, God and World in the Old Testament: A Relational Theology of Creation (Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press, 2005), 25)

[9] Vigneron, “The Christian Mystery,” 152; see also Robert Sokolowski, Presence and Absence: A Philosophical Investigation of Language and Being (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1978), 152.

[10] Kathryn Tanner, God and Creation in Christian Theology: Tyranny or Empowerment? (New York, NY: Basil Blackwell Publishers, 1988), 46–7.

[11] Catherine Mowry LaCugna, “The Trinitarian Mystery of God,” in Systematic Theology: Roman Catholic Perspectives, Vol. 1, eds. Francis Schüssler Fiorenza and John Galvin (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 1991), 156.

[12] Catherine Mowry LaCugna, God for Us: The Trinity and Christian Life (New York, NY: Harper San Francisco, 1993).

[13] Karl Rahner, Foundations of Christian Faith: An Introduction to the Idea of Christianity, trans. William V. Dych (New York, NY: Crossroad Publishing, 2006), 116.

[14] Michael Barnes, Christian Identity and Religious Pluralism: Religions in Conversation (Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press, 1989), 127.

[15] Eric Gregory, Politics and the Order of Love: An Augustinian Ethic of Democratic Citizenship (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2008), 323–8.

[16] Vigneron, “The Christian Mystery,” 186–7. See also Sokolowski, The God of Faith and Reason, especially chapter 4.

[17] Fretheim, The Suffering of God, 71.

[18] Tanner, God and Creation, 46.

[19] Ibid., 47.

[20] Tertullian, Apologeticus, trans. William Reeve, <http://www.tertullian.org/articles/reeve_apology.htm> (accessed January 30, 2016), 17.

[21] Catherine Keller and Laurel Schneider, Eds., Polydoxy: Theology of Multiplicity and Relation (New York, NY: Routledge, 2011), 8.

[22] Bonaventure, Breviloquium: Works of St. Bonaventure, Vol. 9, ed. Robert J. Karris, trans. Dominic V. Monti (St. Bonaventure, NY: Franciscan Institute Publications, 2005), 96.

[23] Augustine, Confessions, I 1.1; Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, <http://www.basilica.org/pages/ebooks/St.%20Thomas%20Aquinas–Summa%20Theologica.pdf> (accessed January 30, 2016), I Q93.4, 7.

[24] Hans–Georg Gadamer, Truth and Method, trans. Joel Weinsheimer and Donald G. Marshall (New York, NY: The Continuum Publishing Company, 2004), 413, 435.

[25] Tanner, God and Creation, 56-7.

[26] Ibid., 46.

[27] Kathryn Tanner, “Creation ex Nihilo as Mixed Metaphor,” Modern Theology 29, no. 2 (2013): 148.

[28] Tanner, God and Creation, 46–7.

[29] Sokolowski, The God of Faith and Reason, 2.

[30] Tanner, God and Creation, 47.

[31] Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, 1, q.4. a.2; see also Thomas Aquinas, On Being and Essence (Toronto, Canada: The Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, 1949), 50.