The following is the last of a three-part series. The first can be found here, the second here. The earlier article by Prof. Hyman to which the author replies can be found here.

In Hegel Contra Sociology Rose argued that the negation of critical consciousness was preserved not just as the interminable repetition of antinomy, but as the consciousness that was changed in and by its self-perficient scepticism. She did not rest with Adorno’s dialectics at a standstill, and would not, I think, rest with Hyman’s version of equivocation. Her aim was to find the logic in which the relation of illusion and critique is its own truth, its own form and content.

She never ceded this logic of experience in her later work. It underpins all that came after, including the concept of experience as a broken middle. Her Adorno book spoke of ‘a changed concept of dialectic’[1] in Adorno. He had to turn to art and aesthetics to fill in the gap, the broken middle, of philosophy and social critique. Rose, however, found the problem to be explicable in terms of social theory per se, and its neo-Kantian prejudices regarding the unknowability of truth.

There has been much discussion about the ‘success’ or otherwise of Rose’s work in dealing with issues in social and political philosophy. But to debate success or failure in this way is to miss entirely the sociological conundrum of antinomical critical consciousness that she never sought to avoid or to transcend or to overcome. In such criticism she is read (as Hegel was) as a commentator and thinker abstracted from the ‘objects’ that she is thinking about. Hence her work is represented and judged in terms of its ability to heal (or not) antinomies that, instead, she sees as inexorable in bourgeois property-based social relations.

Hyman has clearly outlined how Rose’s commentators reproduce the same kind of divide between state and religion that Rose’s Hegelianism calls into question. And he is clear that she is not trying to avoid or to overcome the divide. But she is not just showing the difficulty of thinking the divide. She is thinking the divide in the form in which the divide thinks her, and she is expressing this as the thinking of the absolute. This level of contingency, or complicity, is deeply uncomfortable for a class of commentators and thinkers who demand the analytic rigour and detachment that they assume belongs to ‘criticism.’ They assume for themselves, and demand from her the very kind of critical consciousness that Rose is already knowingly and truly failing to achieve.

So, how is it possible to read Rose, or any Hegelian work, where thinking is not just a ‘sociology of illusion’[2] but a logic of illusion that is self-sustaining as reproduction and critical? This is the same as to ask, what is the logic of the Aufheben in Hegel? Recently, Tubbs has offered an answer to this question that moves Hegelian scholarship, and the reception of Rose, into as yet unchartered territory. In what at first glance strikes the current philosophical Zeitgeist as unusual to say the least, but which has credentials stretching back to the origins of philosophy, Tubbs argues that in Rose’s Hegelianism lies the redefinition of God as education.[3] Tubbs’ work has not yet been taken up yet by Rose scholars, therefore a brief introduction to his overall project is appropriate.[4]

Tubbs and Educational Logic

In broad terms Tubbs argues that the experience of negativity in Hegel and Rose is a ‘logic’ or ‘culture’ of educational experience. Its template is the philosophical experience of positing and necessity. In Philosophy’s Higher Education he populated this template with Hegel’s relation of master and slave, and more recently he has done so by Hegel’s relation of life and death. Overall, his work argues that this culture is suppressed in and by what he calls the logic of mastery as it has defined the course of western intellectual history. That is, it is suppressed ‘when relations between dualities, such as thought and being, theory and practice, subject and object etc., are stated without the accompanying difficulty that is determinative of their relation.’[5] In this regard his approach is very close to that of Hyman’s.

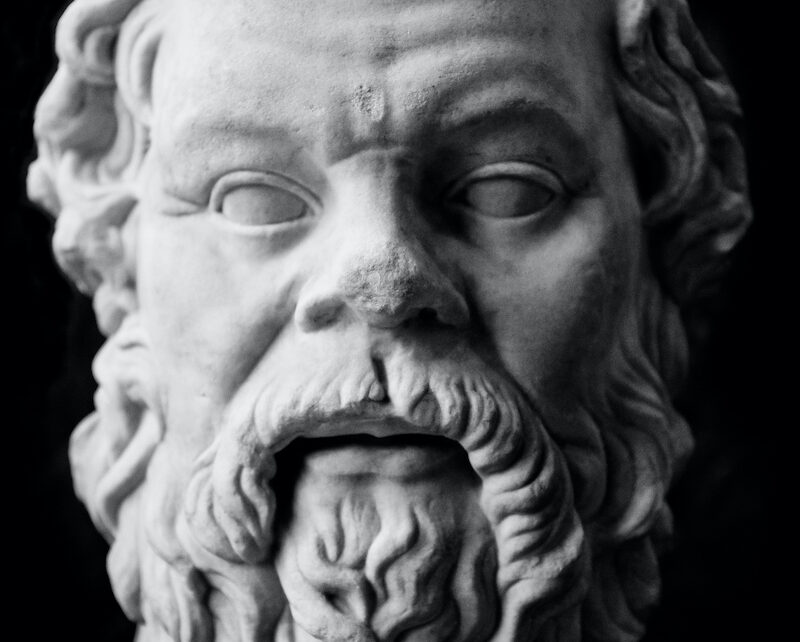

The most recent iteration of the logic of education in Socrates On Trial argues that the necessity of positing and the positing that is necessity are the components of the logic of education and are the formative parts of what constitutes ‘culture’. He sees culture as the work that is the relation of life and death. Life, in becoming an object to itself in thought, posits itself as not death. In doing so it takes its essential nature to be over and against death and the fear and vulnerability that accompanies it.

The illusion that there is a life which is independent of its relation to death is the template of thought’s relation to the object, that is, that there is a mind which is independent of its relation to objects. It takes political form as a relation of master and slave because the master is ‘the life which is certain of itself’ over and against ‘the life that must carry the death that the master has eschewed for himself, which is the slave.’[6]

The misrecognition of life and death takes further shape in Aristotelian logic in the definition of truth as in-itself; independent substance, non-contradictory, unified within itself and lacking any and all contingencies. In contrast, that which is for-another is mediated in being contingent or dependent upon another, and so is defined as error in relation to truth in-itself.[7] The relation is formalized in the Roman world through the law of property, through the ownership of those who lack truth in-themselves; women, children, and slaves.

In demonstrating the reciprocity between the logic of positing and the idea of independence, that the thought which thinks itself – noesis noeseos – is its own object and not for another, Tubbs retrieves the social relations of master (in-itself) and slave (for-another) ‘that serve as the conditions of the possibility for the thinking of objects.’[8] The salient point is that the logic of truth in-itself, like freedom in-itself, is always already a ‘propertied logic’[9] posited in the form of a general logic.

This propertied logic impacts Hyman’s piece because it is this logic that determines the criteria that judge the knowable and the unknowable, and therefore the identity of the idea of God. The radical import of Hegel’s absolute, says Tubbs, lies in its call to reconceptualize the idea of truth within the tradition, and this according to a reworked notion of educational logic which stands within but suppressed by ordinary or propertied logic. His work challenges the logic of mastery with its own vulnerabilities and negations such that it is capable of knowing truth in these negations as learning.

By drawing our attention to the education that lies within the aporias of modern freedom, Tubbs lets God or the absolute emerge as the truth which ‘forms and re-forms itself in what is learned in such difficulties.’[10] It is to say not only that the difficulty of the relation between God and freedom, state and religion, transcendence and immanence, should be retained, as Hyman does, but that it might also commend its own necessity as a reconceptualization of what truth is. It is not just the elements that are negated and preserved in the new relations of Hegel’s new readers.

Relation itself is also negated and preserved in its being formed and reformed. How is this to be thought? How is the necessity of this positing of itself to be knowable? Only as that which posits its own necessity, and for Tubbs, that is only knowable and thinkable as its own formation and reformation, its own culture, its own education. In this logic of positing, rather than of non-contradiction, education can ‘be truth… [can] be the absolute.’[11]

The two works that perhaps best develop this argument are God, Education and Modern Metaphysics and Socrates On Trial. Together they describe how the experience of subject and object carry a necessity of presupposition. The presupposition is the condition of their own possibility; and the necessity is that it presupposes itself. This is not another claim for essence over existence, or for presence over excess, or indeed for anthropocentric metaphysics over posthuman openness.

They are exactly the kinds of divisions that Tubbs argues carry but fail to acknowledge or to do justice to the necessity of presupposition within them. What makes his contribution distinctive is that he finds that this necessity of presupposition, and the presupposition within of it of its own necessity, belongs to a different logic, or what he calls an educational logic. It is in this educational logic that his new conception of God is to be found, and, he has argued, the logic of the Aufheben that makes sense of Rose’s sociological and philosophical project. It is this logic, I argue, that Hyman and others need to look to in order to see how Hegel and Rose are treating the division of knowable and unknowable as a necessity of its own positing. This is how Hegel and Rose are able to think oppositions together in a way different from Hyman.

In God, Education and Modern Metaphysics Tubbs states that the idea being tested is that ‘God, seen in the Western tradition as thought thinking itself (νοησις νοησεως, noesis noeseos,) is experienced by the individual as the educational necessity to know thyself (γνῶθι σεαυτόν, gnōthi seauton).’[12] Its leading questions are ‘can religion—referring specifically to the logic of God shared by the three Abrahamic faiths—be retrieved in the modern rational and reflective mind by the notion of modern metaphysics? Can this modern metaphysics reform the concept of the religious for a modern reflective, critical and sceptical age?

Might it be able to retrieve the religious character of scepticism in an age where spirit is both religious and political, or is both God and freedom? Can modern metaphysics reform the idea of religion so that it comes to know itself in the rational spirit of modernity, and to know the truth of this as education?’[13] And, more bluntly, he offers the following challenge; ‘we are commended to ask if God is not in fact to be found in education, and more challenging still, to ask if God is education.’[14]

This is given what appears to be a more secular treatment in his recent dialogical recreation of Plato’s Republic and Apology, called Socrates On Trial. This and the God book need to be read together as torn halves of an integral freedom, God and the state, to which, however they do not add up. Or, at least, they do not add up according to the ordinary logic of identity or non-contradiction or the logic of mastery, in which as Aristotle said, something which is itself cannot also not be itself.

The Socrates book spells out clearly the history of this logic in western thinking, and the necessity of presupposition that it has carried which consistently and inexorably undermines and collapses the mastery inherent in this logic. Its educational implications are fleshed out in a conversation between Socrates and two interlocuters regarding the possibility of a new ‘un-propertied’ notion of truth in the city. The question is asked, can truth be absolute if it is no longer in-itself and, if so, is it knowable.

Socrates responds by saying that presupposition can ‘be its own kind of truth,’[15] one capable of carrying life and death differently as just social relations. It is an ‘un-propertied logic’, rather than a ‘non-propertied logic’ because presupposition cannot claim immunity from property. Truth which is un-propertied, ‘carries the struggle of the negation of property without resorting to a mastery of non-property.’[16]

Justice in the city is the justice that preserves the struggle of this negation and the only experience that does justice to preserving struggle is, he says, learning. ‘Unlike propertied truth,’ says Socrates, ‘learning is not in denial of its own vulnerability. Which means that education has… a different necessity than that of mastery and property.’[17] In fact, presupposition is the necessity which will always oppose itself. Where the logic of mastery or identity imposes ‘a vicious circle’ of infinite regression, the logic of education ‘preserves what is negated as learning.’[18]

It is this different necessity, argues Tubbs, that offers a different conception of the absolute. Here negative and positive co-exist in the necessity that learning holds within itself. The Socrates book offers a different picture of a polis that tries to live within this educational logic. Tubbs paints a picture of a city where family, civil society and state have their truth within learning, and therefore no longer within the ordinary logic and its masterful notion of truth which, as Tubbs shows, have their own basis in property relations.

He also rewrites the cave in terms of educational logic. All of this is presented by a Socrates who has returned to the city and is charged again with undermining the city by means of his education. He is put on trial and Tubbs is able to offer new verdict that is in harmony with the Socratic life. It is this logic, for Tubbs, and for Hegel and Rose, that makes God and the absolute knowable within the tradition.

Both … And; Know Thyself

The insights of Hyman into the logic of ‘both… and’ regarding the new interpretations draw attention to new aporetic ways of thinking Hegel’s God and the absolute in a post-secular age. He wants to keep Hegel’s God open against the charges of a totalising rationalism and does so without falling into one sided dogmas or scepticisms. It is significant for Hegel and Rose scholarship that he reworks the transcendent dimension in immanence and the immanent dimension in transcendence into a deeper and more difficult conception of the triune God than much of traditional scholarship has been willing to work with and he is right to note that Williams’ more theological reading of Rose and Hegel in the terms of dispossession perhaps comes closest to a more ‘substantial’ account of the absolute as radical political experience.

But in relation to Tubbs insistence on exploring the necessity and logic of aporia, I think that Hyman’s own equivocation regarding aporia is one grounded in the old logic of non-contradiction. This means it still holds to the logic that God is unknowable and that perhaps this is, as he says, the whole point. However, perhaps it is the case that just at the point where Hyman finds the equivocation of aporia necessary and unavoidable, this marks the beginning of a new and old Hegel, one where one logic manifests itself within another logic, or where a logic of education manifests itself in the logic of mastery that still dominates the tradition.

This domination ensures that, even in works championing equivocation and difficulty, the unconditioned God or Absolute is abstracted from the necessity that is its presupposition, which is to say, the educational logic within which God and the absolute are true in learning, and as learning. In Hyman, necessity is acknowledged as the condition of ‘both… and’ but not worked with as its own logic of educational experience.

What I have suggested here is that, perhaps, there is a demand in Hegel and Rose, via Tubbs, to do justice to the educational logic that lies within what is already presupposed in how transcendence and immanence, God and freedom, religion, and the state etc. are to be understood, together and apart. Tubbs’ theory of educational logic, I argue, opens a way for thinking and knowing and living the absolute not just abstractly in all its propertied forms but also educationally in the necessity by which propertied masteries collapse in on themselves.

Tubbs’ work perhaps suggests that while Hegel and Rose reach deeply enough into the logic of the aporias they are working with to find its own necessity, and its own positing of itself as education, it does not lead them to express that truth directly as education, or as a re-conception of God as education. Tubbs’ explanation of this overlooking of education is that the propertied conception of education makes it appear a purely instrumental affair, seemingly unable to carry serious and substantial philosophical weight.

Educational necessity is clearly present in Hyman’s own approach to the new readings of Hegel, and to the way he employs Rose’s work in regard to working with rather than against oppositions. Indeed, it is in many ways the unacknowledged logic of his own thinking about Hegel, Rose and God. He is clear that Williams and Žižek, for example, are implicated in each other, and he seeks to preserve that implication so as not to fall into dogmatism.

This offers a new kind of relation, one whose contradictions are not resolved, but carried. It avoids the binary of having to choose between them, or to choose a winner and a loser in the argument. However, as I have tried to show, when he ends his article with the reaffirmation of the necessity of both … and as a new configuration of God, he does not allow this necessity to be its own truth, or therefore, to be the thinking of God. Still working within the logic that judges truth unknowable and unthinkable, this is neither the God of Hegel nor Rose, or Tubbs.

Rebekah Howes is Senior Lecturer in the Department of Philosophy, Religions, and Liberal Arts at the University of Winchester (UK). She is the author of The Philosophical Voice of Leonard Cohen’ in Spirituality and Desire in Leonard Cohen’s Songs and Poems (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2017).

[1] Ibid.

[2] Rose, The Melancholy Science, p. 146.

[3] The body of work that has explored this argument recently led Rowan Williams to describe Tubbs as ‘the UK’s best educational philosopher.’ See ‘Books of the Year,’ The New Statesman, accessed July 18, 2022, https://www.newstatesman.com/culture/books/2021/11/best-books-year-2021.

[4] Nigel Tubbs is Professor of Philosophical and Educational Thought at the University of Winchester. His theory of philosophical education is developed in the following books: Contradiction of Enlightenment (1997); Philosophy’s Higher Education (2004); Philosophy of the Teacher (2005) Education in Hegel (2008); History of Western Philosophy (2009); Philosophy and Modern Liberal Arts Education (2015); God, Education and Modern Metaphysics, The Logic of “Know Thyself” (2017) and Socrates on Trial (2022). It is also to be found in the theory and practice of two undergraduate programmes in Education Studies and Liberal Arts at the University of Winchester.

[5] Nigel Tubbs, Philosophy’s Higher Education (London: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2004), p. 26.

[6] Nigel Tubbs, Education in Hegel (London: Continuum, 2008), p. 25.

[7] The idea is carried in Aristotle’s notion of the Prime Mover which is its own condition of possibility. Necessity—that it must be itself —is the principle of non-contradiction and the absurdity of infinite regression.

[8] Tubbs, Education in Hegel, p. 49.

[9] Nigel Tubbs, ‘Gillian Rose and Education,’ in Telos 173 (2015), p.126.

[10] Tubbs, Education in Hegel, p. 4.

[11] Tubbs, ‘God, Education and Modern Metaphysics, The Logic of “Know Thyself”’ (New York/London: Routledge, 2017), p. 102.

[12] Tubbs, God, Education and Modern Metaphysics, p. 1.

[13] Ibid., p. xi.

[14] Ibid., p. 1.

[15] Nigel Tubbs, Socrates on Trial (London: Bloomsbury, 2022), p.186.

[16] Tubbs, Socrates on Trial, p. 186.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.