The following article is the first of three installments. It is published as a catalogued .PDF in article in the latest issue of the Journal for Cultural and Religious Theory (22.2).

Introduction

The term “subaltern” comes from the work of Antonio Gramsci, and was used by South Asian historian Ranajit Guha to conceptualize “Subaltern Studies,” encapsulating “history from below,” history as shaped by the non-elites, the subalterns.[1]

Beyond this broad characterization, the concept can be difficult to define sharply. Gyan Prakash, in explicating the field of Subaltern Studies, states that the term ‘subaltern’ “refers to subordination in terms of class, caste, gender, race, language, and culture and was used to signify the centrality of dominant/dominated relationships in history.”[2] Partha Chatterjee points out that Gramsci used the term as a substitute for “proletariat,” to avoid censorship, but that this expanded the scope of its application to peasant-dominated societal contexts, laying the foundations for Guha’s launch of Subaltern Studies.[3]

On the other hand, Peter Thomas returns to Gramsci’s notebooks to extract multiple concepts of the subaltern that are more general than those of the marginalized or the oppressed, extending to the ordinary citizen within the modern state.[4] Nevertheless, El Habib Louai, retracing the terminology through the work of Gramsci, Guha and Gayatri Spivak, suggests that, “Throughout its history since the beginning of the twentieth century, the concept of the subaltern remains one of the most slippery and difficult to define.”[5]

Spivak herself cautions against an overly broad use of the term, that “subaltern” is not “just a classy word for oppressed,” but that “everything that has limited or no access to the cultural imperialism is subaltern – a space of difference.”[6] But Chatterjee credits Spivak with giving the concept of “subalternity” a “new inflection,” taking it beyond class to questions of gender, race and so on.[7] In fact, Spivak asks, “Can the subaltern speak?” querying the possibility of using the hegemonic discourse, and answering in the negative.[8]

Spivak explores how social markers other than class can delineate subaltern status. She focuses particularly on gender, but religion, race and sexual orientation can also be part of the bounding conditions, and this intersectionality is arguably in Gramsci as well.[9] Spivak also criticizes the role of academics, even well-meaning ones, in maintaining power structures and denying subalterns a true voice: an idea that will be one of the foci of this paper.[10]

Subaltern Studies is itself situated within post-colonial studies. Though the concept of the subaltern may be disputed or malleable, it occupies an important place in the broader discourse of postcolonialism. Indeed, Vivek Chibber, in his critique of postcolonial theory, focuses on Subaltern Studies, which he characterizes as, “The most illustrious representative of postcolonial studies in the scholarship on the Global South.”[11] Chibber’s critique revolves around capital and capitalism, the extent to which Subaltern Studies succeeds in providing useful insights into the evolution of capitalism outside the West, and whether it accurately captures the role of subaltern groups in this evolution.[12]

This paper engages with the idea of the subaltern, and with post-colonial theoretical framings, but in a different and novel manner. We argue that the idea of the subaltern in useful for understanding the Sikh community and its evolution in its original South Asian context, but also for the manner of its representation in Western academia. In fact, the subalternization of Sikhs in Western academia is significantly influenced by their subaltern history in a materialist sense.

The outline of the argument is as follows. Sikhism began as a religious formation in the 16th century CE, appealing to a broad cross-section of South Asian society within its home region of Punjab. Many of its doctrines and characteristics challenged subalternity, though with limitations. The origin and evolution of the Sikh community took place within the context of the complete arcs of two successive imperial powers – the Mughals and the British. The specifics of that process of evolution included two crucial markers, those of religion and language, where inequalities of power tended to perpetuate aspects of subalternity, including the scope for self-expression. Ironically, the study of the Sikhs in Western academia has perpetuated and expanded this subaltern status, in ways that the paper describes.[13]

Key features of this latter process have been a foreshortened account of Sikh history and tradition, and a denial of agency to the Sikh community in these academic accounts, so that the subaltern (the community) effectively is not allowed to speak. The foregoing summary uses ‘Sikh’ in a unitary sense, but, like any other tradition or grouping, there is considerable diversity, and that will be addressed as the arguments are laid out.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. The next section provides a bare bones account of the evolution of the Sikh community, trying not to prejudge issues that have been subject to debate, but attempting to justify claims of subaltern status. These debates are discussed in the third section of the paper, where an attempt is made to evaluate different positions, albeit briefly. Section four then discusses the manner in which different scholarly positions are weighted and reproduced, and the reasons for this situation. This is where – we claim – the problem of subalternity arises in a surprising and ironic manner, within postcolonial theorizing. At the same time, the paper is not a defense of tradition or of religious belief.

Rather, it is an excavation in the archeology of knowledge production, one that is informed by the perspective of subalternity to highlight inequalities in the reception of certain voices. The final section concludes by summarizing its intended contribution, that of using the case of the Sikhs to highlight aspects of subalternity that are often buried, and using the 2020-21 farmer protests in India to illustrate the weakness of some recent theorizing.

Sikhs: A Summary[14]

The Sikh tradition begins with Nanak (1469-1539 CE), considered a Guru, or spiritual teacher, by his followers. To what extent his intention was to establish a new religious community, whether the term “religion” is appropriate, and how much his message was a reworking of those of others who came before him, are all matters of scholarly debate. Even within the Sikh community, there are varied opinions on these matters. However, it is reasonably well established that he traveled widely during his lifetime, seeking to spread his message, before settling down in a specific place in the Punjab region of South Asia, where he was surrounded by followers. These followers were also in other places where Nanak had previously traveled.

Nanak composed verses that were meant to be sung to musical measures (raags), which consist of praise of the Divine, reflections on the nature of the Divine, and moral and ethical guidance. In his verses, he criticized unjust uses of power by government officials and rulers, as well as the insincere practices of figures of religious significance or authority, including Brahmin priests (pandits), Muslim clerics, and members of yogic orders (siddhs). He advocated for personal internal transformation, through “truthful living,” which included reflection on the Divine, charity, and purity of thought and action. “Sikh” means student, learner or disciple, and it is used by Nanak in this sense in his writings for his followers. Another term used in this sense is gurmukh, literally someone who faces the Guru, and the terms are used together, or combined (gursikh) in ways that convey the general normative meaning of being a “Sikh.”

Nanak had nine human successors, each of whom used the signature “Nanak” in their own writings. Contemporary verses by bards in the Sikh community indicate that this was seen as a continuity of spirit or “light,” the same divine inspiration that was in Nanak. In most cases, the successor was chosen by the incumbent Guru, unless the latter met an unexpected end. In two cases, the fifth and ninth Gurus, this was at the hands of Mughal authorities, in the first case after some form of physical torture, in the second, in a public execution by beheading.

Before his demise (1606 CE), the fifth Guru, Arjan, compiled the writings of the first five Gurus into a single canonical text. Later in the 17th century, the verses of the ninth Guru were added to this compilation. This text also included verses of over a dozen others: some who are now associated with what is termed the bhakti movement, bards within the Guru’s darbar (court), and one Sufi Muslim spiritual leader. The Sikh Gurus themselves used the appellation bhagat (the Punjabi equivalent to bhakta) for a defined set of individuals, indicating that this grouping was understood as such in the 16thcentury.

A strong Sikh tradition holds that the tenth and last human Guru, Gobind Singh, appointed the canonical text as the Guru of the Sikhs, and it firmly holds that status in the community, being the center of worship in multiple forms (recitation, singing, listening, interpretation, discussion, and ceremonial actions). This tradition is documented in contemporaneous sources of that time, the early 18th century. The text is now known as the Guru Granth Sahib (GGS), the last term being meant to convey respect. Often, additional terms of respect are added.

The text was originally authenticated by Guru Arjan, and immediately began to be copied and distributed to Sikh congregations wherever they were in South Asia. The GGS is written in a regional script, systematized by the Sikh Gurus, and now always known as Gurmukhi, because of its association with the text. The languages in the GGS are a range of regional vernaculars of the period.[15]

In their writings, Guru Nanak and his successors viewed caste markers and associated social and spiritual hierarchies as irrelevant for, and even inimical to, spiritual advancement. This was aligned with the caste status (including outcastes) and writings of several of the bhagats whose work is included in the GGS, although the Gurus themselves were all from a merchant caste.

According to the collected verses in the GGS, the goal of a Sikh was to make a connection to the Divine, by becoming free of a sense of separation from the Divine and Divine creation. This had to be achieved while engaging in worldly responsibilities, and not through asceticism or renunciation. Therefore, honest work and material success are acceptable, but within boundaries of fairness, justice and equity, and without allowing material success to engender pride or arrogance. Actively sharing the fruits of material success is important.

As the Sikh community evolved and expanded, the message of the Gurus attracted a wide range of followers, including erstwhile outcastes, and lower castes such as artisans and peasants. A major numerical component of the growth of the Sikh community came from the Jats, a range of clans that had migrated into the region in earlier centuries. They were originally pastoralists who were, in this period, adopting agriculture and local religious identities. Evidence from early 17th century writings, of a prominent Sikh (Gurdas Bhalla) suggests that some Jats were part of the Sikh community by this time, and they constitute a majority in the contemporary community.

The century and a half after Arjan’s death was marked by intensified disputes over succession, doctrinal differences connected to those disputes, and a pattern of conflict and accommodation with successive Mughal emperors and their representatives. This pattern also included imperial attempts to control the succession to the mantle of Guru. A key event in the community’s evolution occurred at the end of the 17th century, when Gobind Singh created a new initiated order of Sikhs, the Khalsa. The Khalsa were to have direct allegiance to the Guru, without the intermediaries who had played an institutional role as the community had grown and spread.

They were to abandon caste ties by adopting the common surname “Singh,” – as did Gobind himself at this time – and adhere to a code of conduct and dress, including carrying a dagger or sword (kirpan), and keeping uncut hair (kesh), covered with a turban. These visible markers of identity have been associated with an ideal of fearlessness, and willingness to stand up against any form of oppression. A metaphor that came to be commonly used was that the creation of the Khalsa would turn sparrows into hawks.[16]

The significance and position of the Khalsa within the Sikh community has been a matter of continual debate from its inception, including its meaning, status, precise markers, and so on. Scholars of the Sikhs have participated in these debates, in ways that, as will be discussed later in the paper, are often at the center of issues of subalternity. In contemporary India, about three quarters of Sikhs keep uncut hair, but only 20-30 percent of this number have undergone the formal Khalsa initiation.[17]

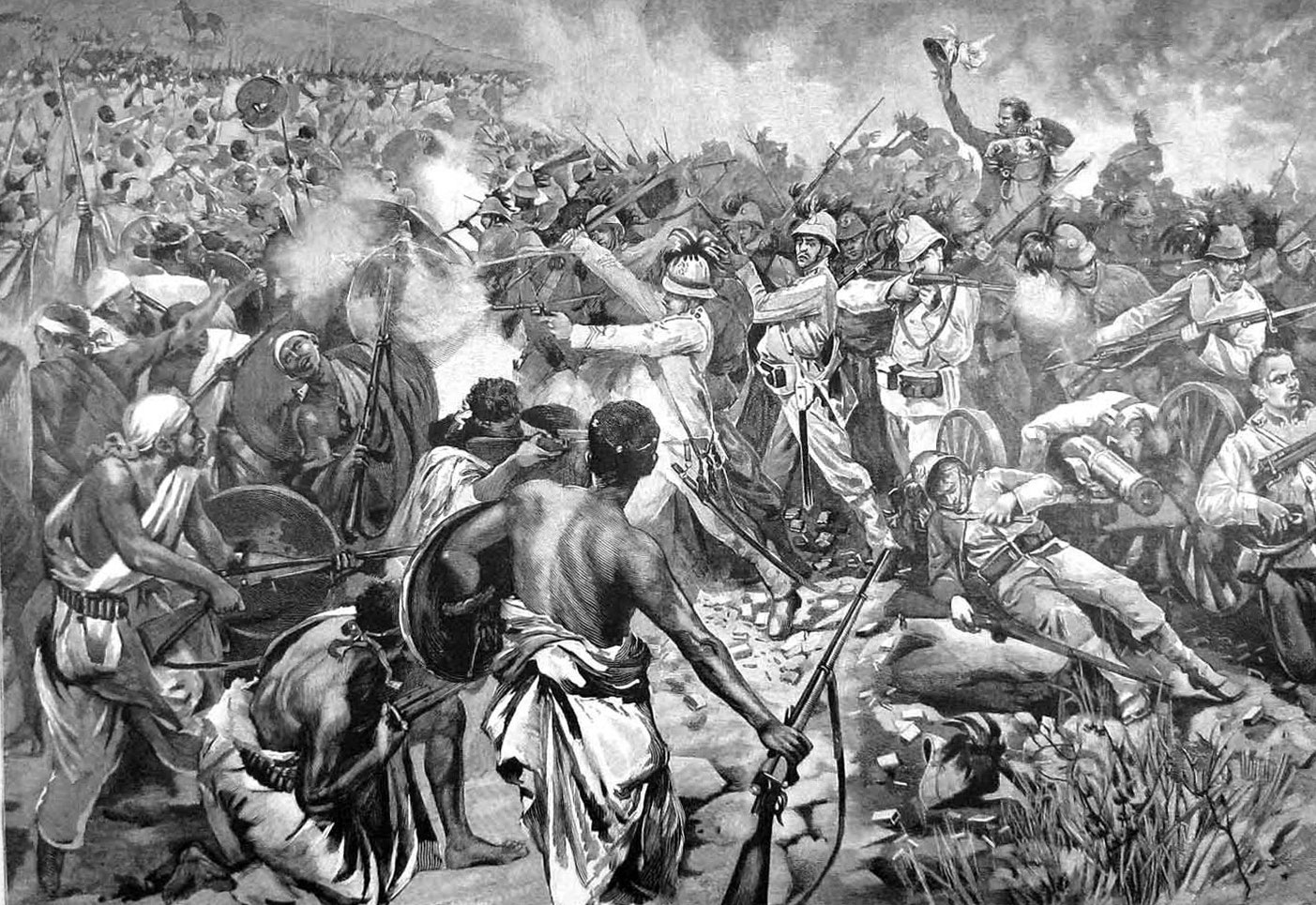

As the 18th century progressed, the Khalsa became a force of resistance to the Mughal authorities in Punjab, as well as to invaders from the northwest, as the empire began to collapse. At first, a confederacy of small Khalsa-ruled principalities emerged, and by the end of the 18th century, most of these had been absorbed into a kingdom led by one of the Khalsa chiefs, Ranjit Singh. By this time, most of South Asia was already under the control of the East India Company, and they completed their conquest by military victories and annexation of Punjab in 1849 CE.

The latter half of the 19th century saw the Sikh community becoming entangled in the British colonial project, and they followed Hindus and Muslims in negotiating this new situation, in terms of legal and political structures, language, jobs and new technologies. All three communities worked to define themselves to fit the colonial legal and political framework, as well as pursuing educational and other projects to position their members more favorably. For Sikhs, as a relatively small community with a short history and no national level presence, defining themselves as distinct was particularly important. This need was heightened by claims of inclusion in a larger “Hindu” tent,[18] and explicit efforts at conversion.[19]

This period is, of course, the focus of post-colonial studies, and Sikhs are variously viewed as having reformed their tradition, or as having reinvented it. The Sikhs who led this project are viewed as inspirational heroes, aggressive usurpers of tradition, or victims of the trauma of colonization. In all these cases, there is a strong focus on leadership and elites of various kinds, very much the opposite of an approach that would be consistent with the Subaltern Studies project.

An important feature in historical accounts of the late 19th and 20th centuries, as British colonization was negotiated, then opposed and rejected by the indigenous populations, is the minority status of the Sikh community, even within the region of Punjab, where they were, and remain, concentrated. When Punjab was partitioned as the British left in 1947, being a numerical minority almost everywhere created a situation of extreme precarity. Sikhs have continued to struggle with minority status, even after the creation through division of a Sikh-majority state of Punjab in 1966, and conflicts of various forms with the national government have been persistent, including a period of violence and repression in the 1980s and 1990s. Much of the growth of scholarship on the Sikhs has occurred during this period and its aftermath, and it has arguably shaped that scholarship, as well as its perception by members of the Sikh community.

Defining the Sikhs

Many of the issues relating to the definition of the Sikh community revolve around issues of identity and origins. One complication is that the community is heterogeneous, and there are different perspectives from within the community. However, it is not clear that these features are any different or more extreme than for other religious traditions. This assessment, and possible special features of analysis of the Sikhs are taken up in the next section.

A very basic issue is that of antecedents of the Sikh tradition, and Nanak’s message in particular. A common scholarly position is that Nanak can be placed within a so-called Sant tradition, consisting of nirguna bhaktas such as Kabir, Namdev and Ravidas, whose writings are included in the GGS, and who were chronologically prior to Nanak. The most vigorous proponent of this view is Hew McLeod, but it can be found initially in the work of Pitamber Barthwal. [20]

However, the category of Sants was created in the 19th century, whereas the concept of bhaktas/bhagats existed at the time of the early evolution of the Sikh tradition.[21] Furthermore, Nanak does not mention or otherwise acknowledge the bhagats: their introduction into the Sikh tradition comes with Nanak’s second successor, and the structure of the GGS, as well as specific verses, indicate their conceptual subordination to the line of Nanak and his successors. None of Nanak’s successors label the bhagats as Sants. Claims that the language of the GGS was that of the “Sants” turn out to be circular.[22]

Introduction

The term “subaltern” comes from the work of Antonio Gramsci, and was used by South Asian historian Ranajit Guha to conceptualize “Subaltern Studies,” encapsulating “history from below,” history as shaped by the non-elites, the subalterns.[1] Beyond this broad characterization, the concept can be difficult to define sharply. Gyan Prakash, in explicating the field of Subaltern Studies, states that the term ‘subaltern’ “refers to subordination in terms of class, caste, gender, race, language, and culture and was used to signify the centrality of dominant/dominated relationships in history.”[2] Partha Chatterjee points out that Gramsci used the term as a substitute for “proletariat,” to avoid censorship, but that this expanded the scope of its application to peasant-dominated societal contexts, laying the foundations for Guha’s launch of Subaltern Studies.[3] On the other hand, Peter Thomas returns to Gramsci’s notebooks to extract multiple concepts of the subaltern that are more general than those of the marginalized or the oppressed, extending to the ordinary citizen within the modern state.[4] Nevertheless, El Habib Louai, retracing the terminology through the work of Gramsci, Guha and Gayatri Spivak, suggests that, “Throughout its history since the beginning of the twentieth century, the concept of the subaltern remains one of the most slippery and difficult to define.”[5]

Spivak herself cautions against an overly broad use of the term, that “subaltern” is not “just a classy word for oppressed,” but that “everything that has limited or no access to the cultural imperialism is subaltern – a space of difference.”[6] But Chatterjee credits Spivak with giving the concept of “subalternity” a “new inflection,” taking it beyond class to questions of gender, race and so on.[7] In fact, Spivak asks, “Can the subaltern speak?” querying the possibility of using the hegemonic discourse, and answering in the negative.[8] Spivak explores how social markers other than class can delineate subaltern status. She focuses particularly on gender, but religion, race and sexual orientation can also be part of the bounding conditions, and this intersectionality is arguably in Gramsci as well.[9] Spivak also criticizes the role of academics, even well-meaning ones, in maintaining power structures and denying subalterns a true voice: an idea that will be one of the foci of this paper.[10]

Subaltern Studies is itself situated within post-colonial studies. Though the concept of the subaltern may be disputed or malleable, it occupies an important place in the broader discourse of postcolonialism. Indeed, Vivek Chibber, in his critique of postcolonial theory, focuses on Subaltern Studies, which he characterizes as, “The most illustrious representative of postcolonial studies in the scholarship on the Global South.”[11] Chibber’s critique revolves around capital and capitalism, the extent to which Subaltern Studies succeeds in providing useful insights into the evolution of capitalism outside the West, and whether it accurately captures the role of subaltern groups in this evolution.[12]

This paper engages with the idea of the subaltern, and with post-colonial theoretical framings, but in a different and novel manner. We argue that the idea of the subaltern in useful for understanding the Sikh community and its evolution in its original South Asian context, but also for the manner of its representation in Western academia. In fact, the subalternization of Sikhs in Western academia is significantly influenced by their subaltern history in a materialist sense. The outline of the argument is as follows. Sikhism began as a religious formation in the 16th century CE, appealing to a broad cross-section of South Asian society within its home region of Punjab. Many of its doctrines and characteristics challenged subalternity, though with limitations. The origin and evolution of the Sikh community took place within the context of the complete arcs of two successive imperial powers – the Mughals and the British. The specifics of that process of evolution included two crucial markers, those of religion and language, where inequalities of power tended to perpetuate aspects of subalternity, including the scope for self-expression. Ironically, the study of the Sikhs in Western academia has perpetuated and expanded this subaltern status, in ways that the paper describes.[13] Key features of this latter process have been a foreshortened account of Sikh history and tradition, and a denial of agency to the Sikh community in these academic accounts, so that the subaltern (the community) effectively is not allowed to speak. The foregoing summary uses ‘Sikh’ in a unitary sense, but, like any other tradition or grouping, there is considerable diversity, and that will be addressed as the arguments are laid out.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. The next section provides a bare bones account of the evolution of the Sikh community, trying not to prejudge issues that have been subject to debate, but attempting to justify claims of subaltern status. These debates are discussed in the third section of the paper, where an attempt is made to evaluate different positions, albeit briefly. Section four then discusses the manner in which different scholarly positions are weighted and reproduced, and the reasons for this situation. This is where – we claim – the problem of subalternity arises in a surprising and ironic manner, within postcolonial theorizing. At the same time, the paper is not a defense of tradition or of religious belief. Rather, it is an excavation in the archeology of knowledge production, one that is informed by the perspective of subalternity to highlight inequalities in the reception of certain voices. The final section concludes by summarizing its intended contribution, that of using the case of the Sikhs to highlight aspects of subalternity that are often buried, and using the 2020-21 farmer protests in India to illustrate the weakness of some recent theorizing.

Sikhs: A Summary[14]

The Sikh tradition begins with Nanak (1469-1539 CE), considered a Guru, or spiritual teacher, by his followers. To what extent his intention was to establish a new religious community, whether the term “religion” is appropriate, and how much his message was a reworking of those of others who came before him, are all matters of scholarly debate. Even within the Sikh community, there are varied opinions on these matters. However, it is reasonably well established that he traveled widely during his lifetime, seeking to spread his message, before settling down in a specific place in the Punjab region of South Asia, where he was surrounded by followers. These followers were also in other places where Nanak had previously traveled.

Nanak composed verses that were meant to be sung to musical measures (raags), which consist of praise of the Divine, reflections on the nature of the Divine, and moral and ethical guidance. In his verses, he criticized unjust uses of power by government officials and rulers, as well as the insincere practices of figures of religious significance or authority, including Brahmin priests (pandits), Muslim clerics, and members of yogic orders (siddhs). He advocated for personal internal transformation, through “truthful living,” which included reflection on the Divine, charity, and purity of thought and action. “Sikh” means student, learner or disciple, and it is used by Nanak in this sense in his writings for his followers. Another term used in this sense is gurmukh, literally someone who faces the Guru, and the terms are used together, or combined (gursikh) in ways that convey the general normative meaning of being a “Sikh.”

Nanak had nine human successors, each of whom used the signature “Nanak” in their own writings. Contemporary verses by bards in the Sikh community indicate that this was seen as a continuity of spirit or “light,” the same divine inspiration that was in Nanak. In most cases, the successor was chosen by the incumbent Guru, unless the latter met an unexpected end. In two cases, the fifth and ninth Gurus, this was at the hands of Mughal authorities, in the first case after some form of physical torture, in the second, in a public execution by beheading.

Before his demise (1606 CE), the fifth Guru, Arjan, compiled the writings of the first five Gurus into a single canonical text. Later in the 17th century, the verses of the ninth Guru were added to this compilation. This text also included verses of over a dozen others: some who are now associated with what is termed the bhakti movement, bards within the Guru’s darbar (court), and one Sufi Muslim spiritual leader. The Sikh Gurus themselves used the appellation bhagat (the Punjabi equivalent to bhakta) for a defined set of individuals, indicating that this grouping was understood as such in the 16thcentury. A strong Sikh tradition holds that the tenth and last human Guru, Gobind Singh, appointed the canonical text as the Guru of the Sikhs, and it firmly holds that status in the community, being the center of worship in multiple forms (recitation, singing, listening, interpretation, discussion, and ceremonial actions). This tradition is documented in contemporaneous sources of that time, the early 18th century. The text is now known as the Guru Granth Sahib (GGS), the last term being meant to convey respect. Often, additional terms of respect are added. The text was originally authenticated by Guru Arjan, and immediately began to be copied and distributed to Sikh congregations wherever they were in South Asia. The GGS is written in a regional script, systematized by the Sikh Gurus, and now always known as Gurmukhi, because of its association with the text. The languages in the GGS are a range of regional vernaculars of the period.[15]

In their writings, Guru Nanak and his successors viewed caste markers and associated social and spiritual hierarchies as irrelevant for, and even inimical to, spiritual advancement. This was aligned with the caste status (including outcastes) and writings of several of the bhagats whose work is included in the GGS, although the Gurus themselves were all from a merchant caste. According to the collected verses in the GGS, the goal of a Sikh was to make a connection to the Divine, by becoming free of a sense of separation from the Divine and Divine creation. This had to be achieved while engaging in worldly responsibilities, and not through asceticism or renunciation. Therefore, honest work and material success are acceptable, but within boundaries of fairness, justice and equity, and without allowing material success to engender pride or arrogance. Actively sharing the fruits of material success is important.

As the Sikh community evolved and expanded, the message of the Gurus attracted a wide range of followers, including erstwhile outcastes, and lower castes such as artisans and peasants. A major numerical component of the growth of the Sikh community came from the Jats, a range of clans that had migrated into the region in earlier centuries. They were originally pastoralists who were, in this period, adopting agriculture and local religious identities. Evidence from early 17th century writings, of a prominent Sikh (Gurdas Bhalla) suggests that some Jats were part of the Sikh community by this time, and they constitute a majority in the contemporary community.

The century and a half after Arjan’s death was marked by intensified disputes over succession, doctrinal differences connected to those disputes, and a pattern of conflict and accommodation with successive Mughal emperors and their representatives. This pattern also included imperial attempts to control the succession to the mantle of Guru. A key event in the community’s evolution occurred at the end of the 17th century, when Gobind Singh created a new initiated order of Sikhs, the Khalsa. The Khalsa were to have direct allegiance to the Guru, without the intermediaries who had played an institutional role as the community had grown and spread. They were to abandon caste ties by adopting the common surname “Singh,” – as did Gobind himself at this time – and adhere to a code of conduct and dress, including carrying a dagger or sword (kirpan), and keeping uncut hair (kesh), covered with a turban. These visible markers of identity have been associated with an ideal of fearlessness, and willingness to stand up against any form of oppression. A metaphor that came to be commonly used was that the creation of the Khalsa would turn sparrows into hawks.[16] The significance and position of the Khalsa within the Sikh community has been a matter of continual debate from its inception, including its meaning, status, precise markers, and so on. Scholars of the Sikhs have participated in these debates, in ways that, as will be discussed later in the paper, are often at the center of issues of subalternity. In contemporary India, about three quarters of Sikhs keep uncut hair, but only 20-30 percent of this number have undergone the formal Khalsa initiation.[17]

As the 18th century progressed, the Khalsa became a force of resistance to the Mughal authorities in Punjab, as well as to invaders from the northwest, as the empire began to collapse. At first, a confederacy of small Khalsa-ruled principalities emerged, and by the end of the 18th century, most of these had been absorbed into a kingdom led by one of the Khalsa chiefs, Ranjit Singh. By this time, most of South Asia was already under the control of the East India Company, and they completed their conquest by military victories and annexation of Punjab in 1849 CE. The latter half of the 19th century saw the Sikh community becoming entangled in the British colonial project, and they followed Hindus and Muslims in negotiating this new situation, in terms of legal and political structures, language, jobs and new technologies. All three communities worked to define themselves to fit the colonial legal and political framework, as well as pursuing educational and other projects to position their members more favorably. For Sikhs, as a relatively small community with a short history and no national level presence, defining themselves as distinct was particularly important. This need was heightened by claims of inclusion in a larger “Hindu” tent,[18] and explicit efforts at conversion.[19]

This period is, of course, the focus of post-colonial studies, and Sikhs are variously viewed as having reformed their tradition, or as having reinvented it. The Sikhs who led this project are viewed as inspirational heroes, aggressive usurpers of tradition, or victims of the trauma of colonization. In all these cases, there is a strong focus on leadership and elites of various kinds, very much the opposite of an approach that would be consistent with the Subaltern Studies project.

An important feature in historical accounts of the late 19th and 20th centuries, as British colonization was negotiated, then opposed and rejected by the indigenous populations, is the minority status of the Sikh community, even within the region of Punjab, where they were, and remain, concentrated. When Punjab was partitioned as the British left in 1947, being a numerical minority almost everywhere created a situation of extreme precarity. Sikhs have continued to struggle with minority status, even after the creation through division of a Sikh-majority state of Punjab in 1966, and conflicts of various forms with the national government have been persistent, including a period of violence and repression in the 1980s and 1990s. Much of the growth of scholarship on the Sikhs has occurred during this period and its aftermath, and it has arguably shaped that scholarship, as well as its perception by members of the Sikh community.

Defining the Sikhs

Many of the issues relating to the definition of the Sikh community revolve around issues of identity and origins. One complication is that the community is heterogeneous, and there are different perspectives from within the community. However, it is not clear that these features are any different or more extreme than for other religious traditions. This assessment, and possible special features of analysis of the Sikhs are taken up in the next section.

A very basic issue is that of antecedents of the Sikh tradition, and Nanak’s message in particular. A common scholarly position is that Nanak can be placed within a so-called Sant tradition, consisting of nirguna bhaktas such as Kabir, Namdev and Ravidas, whose writings are included in the GGS, and who were chronologically prior to Nanak. The most vigorous proponent of this view is Hew McLeod, but it can be found initially in the work of Pitamber Barthwal. [20] However, the category of Sants was created in the 19th century, whereas the concept of bhaktas/bhagats existed at the time of the early evolution of the Sikh tradition.[21] Furthermore, Nanak does not mention or otherwise acknowledge the bhagats: their introduction into the Sikh tradition comes with Nanak’s second successor, and the structure of the GGS, as well as specific verses, indicate their conceptual subordination to the line of Nanak and his successors. None of Nanak’s successors label the bhagats as Sants. Claims that the language of the GGS was that of the “Sants” turn out to be circular.[22]

Nirvikar Singh is Co-Director of the Center for Analytical Finance at UCSC, of which he was the founding Director. From 2010 to 2020, he held the Sarbjit Singh Aurora Chair of Sikh and Punjabi Studies at UCSC. He has previously directed the UCSC South Asian Studies Initiative. He has served as a member of the Advisory Group to the Finance Minister of India on G-20 matters, and Consultant to the Chief Economic Adviser, Ministry of Finance, Government of India. He is currently serving on the Expert Group on post-Covid-19 economic recovery formed by the Chief Minister of Punjab state in India. At UCSC, he has previously served as Director of the Santa Cruz Center for International Economics, Co-Director of the Center for Global, International and Regional Studies, and Special Advisor to the Chancellor.

[1]Antonio Gramsci, Letters from Prison, Edited and translated by Lynn Lawner (New York and London: Harper and Row, 1973); Ranajit Guha, “On Some Aspects of the Historiography of Colonial India.” In Subaltern Studies: Writings on South Asian Society and History, Vol. VII, edited by Ranajit Guha (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1982), 37-44.

[2] Gyan Prakash, “Subaltern Studies as Postcolonial Criticism,” American Historical Review, 99 (5) (1994): 1477.

[3] Partha Chatterjee, “Subaltern Studies: A Conversation with Partha Chatterjee,” Interview by Richard McGrail, 2012, https://journal.culanth.org/index.php/ca/subaltern-studies-partha-chatterjee, accessed March 7, 2023.

[4] Peter D. Thomas, “Refiguring the Subaltern,” Political Theory, 46 (6), 2018: 861-884.

[5] El Habib Louai, “Retracing the concept of the subaltern from Gramsci to Spivak: Historical developments and new applications,” African Journal of History and Culture, 4 (1), 2012: 5.

[6] Gayatri Spivak, quoted in Leon de Kock, “Interview with Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak: New Nation Writers Conference in South Africa,” ARIEL: A Review of International English Literature. 23 (3), 1992: 45.

[7] Chatterjee, “Subaltern Studies.”

[8] Gayatri Spivak, “Can the Subaltern Speak?” in Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, eds. Cary Nelson and Lawrence Grossberg, Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1988: 271-313.

[9] Green, Marcus E., “Race, class, and religion: Gramsci’s conception of subalternity,” in The Political Philosophies of Antonio Gramsci and B. R. Ambedkar: Itineraries of Dalits and Subalterns, ed. Cosimo Zene (New York: Routledge, 2013): 116-28.

[10] Spivak (“Can the Subaltern Speak?,”280) somewhat strongly terms this phenomenon “epistemic violence.”

[11] Vivek Chibber, Postcolonial Theory and the Specter of Capital (New York: Verso, 2013) 5.

[12] Chibber’s critique prompted spirited discussion and fierce debate, e.g., Partha Chatterjee, “Subaltern Studies and “Capital,”” Economic and Political Weekly, 2013: 48, 37, 69-75.; Vivek Chibber, “Subaltern Studies Revisited: A Response to Partha Chatterjee,” https://as.nyu.edu/content/dam/nyu-as/faculty/documents/SubalternStudies-Revisited.pdf, February 21, 2014, accessed March 7, 2023; Ho-fung Hung, George Steinmetz, Bruce Cumings, Michael Schwartz, William H. Sewell, Jr., David Pedersen, and Vivek Chibber, “Review Symposium on Vivek Chibber’s Postcolonial Theory and The Specter of Capital,” Journal of World-Systems Research, 20 (2), 2016: 281-317.; and Rosie Warren, ed., The Debate on Postcolonial Theory and the Specter of Capital (New York: Verso, 2016). Much of the debate concerns very broad questions around the nature and evolution of capitalism, the relative roles of individuals and communities, and the extent of the universal vs. the specific in the analysis of societal change. Some of these issues are pertinent in the case of the Sikhs, and will be addressed at the appropriate points. A useful brief summary assessment of Chibber and the debates that followed is Alex Sager, “Review of Vivek Chibber: Postcolonial Theory and the Specter of Capital, Marx & Philosophy Review of Books, https://marxandphilosophy.org.uk/reviews/7946_postcolonial-theory-and-the-specter-of-capital-review-by-alex-sager/#comments, October 2014, accessed March 7, 2023 . Spivak (“Can the Subaltern Speak?”) has her own critique of the Subaltern Studies group: for an elementary exposition of Spivak’s various arguments, see Graham K Riach., An Analysis of Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’s Can the Subaltern Speak? (London: Macat International, 2017). A collection of assessments of the impact of Spivak’s ideas is in Rosalind Morris, ed., Can the Subaltern Speak? Reflections on the History of an Idea (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010).

[13] There are several Sikh Studies endowed chairs in US universities, but they have arguably perpetuated the post-colonial foreshortening of Sikh history. The approach to the subaltern in different contexts of knowledge production has led to explorations in a variety of directions, such as the work of Seana McGovern, Education, Modern Development, and Indigenous Knowledge: An Analysis of Academic Knowledge Production, (Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2013); and Antonia Darder, “Decolonizing Interpretive Research: Subaltern Sensibilities and the Politics of Voice,” Qualitative Research Journal, 18 (2018): 94-104.

[14] Arguably, the most neutral account of the Sikhs and their history is Jagtar Singh Grewal, The Sikhs of the Punjab (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1994), but many earlier histories are also available, offering a range of interpretations. The account in this section is based on evidence that is used by these historians, avoiding interpretational questions. Other recent historical summaries include Wystan Hewat McLeod, The Sikhs: History, Religion, and Society (New York: Columbia University Press, 1989); and Gurinder Singh Mann, The Making of Sikh Scripture (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001).

[15]Christoper Shackle, An Introduction to the Sacred Language of the Sikhs (New Delhi: Heritage Publishers, 1983).

[16] Purnima Dhavan, When Sparrows Became Hawks: The Making of the Sikh Warrior Tradition, 1699-1799 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011).

[17] Pew Research Center. Religion in India: Tolerance and Segregation (Washington, DC: Pew Research Center, 2021).

[18] Most prominently, Mohandas Gandhi wrote, as late as 1936, that “Today I will only say that to me Sikhism is a part of Hinduism.” He was opposing Bhimrao Ambedkar’s plan to lead his Mahar community of outcastes in converting to Sikhism. See Mohandas K. Gandhi, Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, Volumes 1-100 (New Delhi: Publications Division, Ministry of Information & Broadcasting, Government of India, 1956-94), Vol. 63, p. 267.

[19] Kenneth W. Jones, Arya Dharm: Hindu Consciousness in 19th-Century Punjab (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1976).

[20] See Wystan Hewat McLeod, Guru Nanak and the Sikh Religion (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1968); and Pitamber D. Barthwal, The Nirguna School of Hindi Poetry, Banaras: Indian Book Shop, republished with minor changes as Traditions of Indian Mysticism: based upon Nirguna School of Hindi Poetry (New Delhi: Heritage Publishers, 1936).

[21] On the origin of the “Sant” category, see Mark Juergensmeyer, “The Radhasoami Revival,” in Karine Schomer and W.H. McLeod, eds., The Sants: Studies in a Devotional Tradition of India (Delhi: Berkeley Religious Studies Series and Motilal Banarsidass, 1987): 329-355

[22] These arguments are detailed in Nirvikar Singh, “Guru Nanak and the Sants: A Reappraisal,” International Journal of Punjab Studies 8 (1) (2001): 1-34.