The following is the first part in a two-part installment.

Biblical hermeneutics, studied reflection upon interpretation of scriptural passages, has not remained static in method or approach over the centuries. It has manifestly evolved in response to evolving cultural forces generally, as the needs and opportunities of Christian communities have changed and changed again over time. As numerous scholars have observed, the writers of the books of the New Testament are already to be found re-interpreting works of the Hebrew Bible, the “Old” Testament.”

This writer cannot claim to have become thoroughly immersed in the long history of evolving biblical interpretation, nor to have immersed himself in the development over the past two centuries of the academic enterprise of newly named “hermeneutics” as a field connecting formal theology and philosophical theology and epistemology with developing linguistic and literary theory.

But what is especially relevant in this more “recent” enterprise of formal hermeneutical reflection – relevant now and especially to this writer – much of it lately conducted by philosophers and linguistic theorists without professed confessional religious interest, has been the wide ranging use of theory and reflection drawn from disparate academic quarters. As a field of inquiry with several foci, and in becoming interdisciplinary, hermeneutics has perhaps appropriately been described recently as now a “minefield.”[1]

An innovative hermeneutic from a new perspective such as I propose may indeed benefit those in Christian communities who seek suggestions for how now in an increasingly skeptical, secular time to “read” and to embrace not only challenging scriptural passages but the confessional language which has long arisen and arises still out of acquired personal faith (in doctrine, liturgy, homily, personal and public prayer, as well as intimate conversation).

In awareness of my limitations as a scholar trained and encouraged to risk working across lines that traditionally separate disciplines such as theology, philosophy, literary and cultural studies, but also in the belief that that careful, measured interdisciplinary projects hold potential for re-invigorating reflection and offering vital new insights, I offer what follows as a useful contribution to ongoing hermeneutical reflection. The interdisciplinary license and latitude in what follows reflects one individual’s integration of disparate career recognitions. Though I intend the proposal argued to serve and provoke a wide readership, the path will be haunted inevitably by the autobiographical.

I will sketch a proposal of a more timely, more serviceable hermeneutic by, in turn, developing the relevance of disparate, perhaps heretofore unlikely sources, connecting the dots, as it were, to offer a theory of interpretation that may, for some, meet the need for a new way to read the Bible and to use traditional religious language with personal authenticity and commitment.

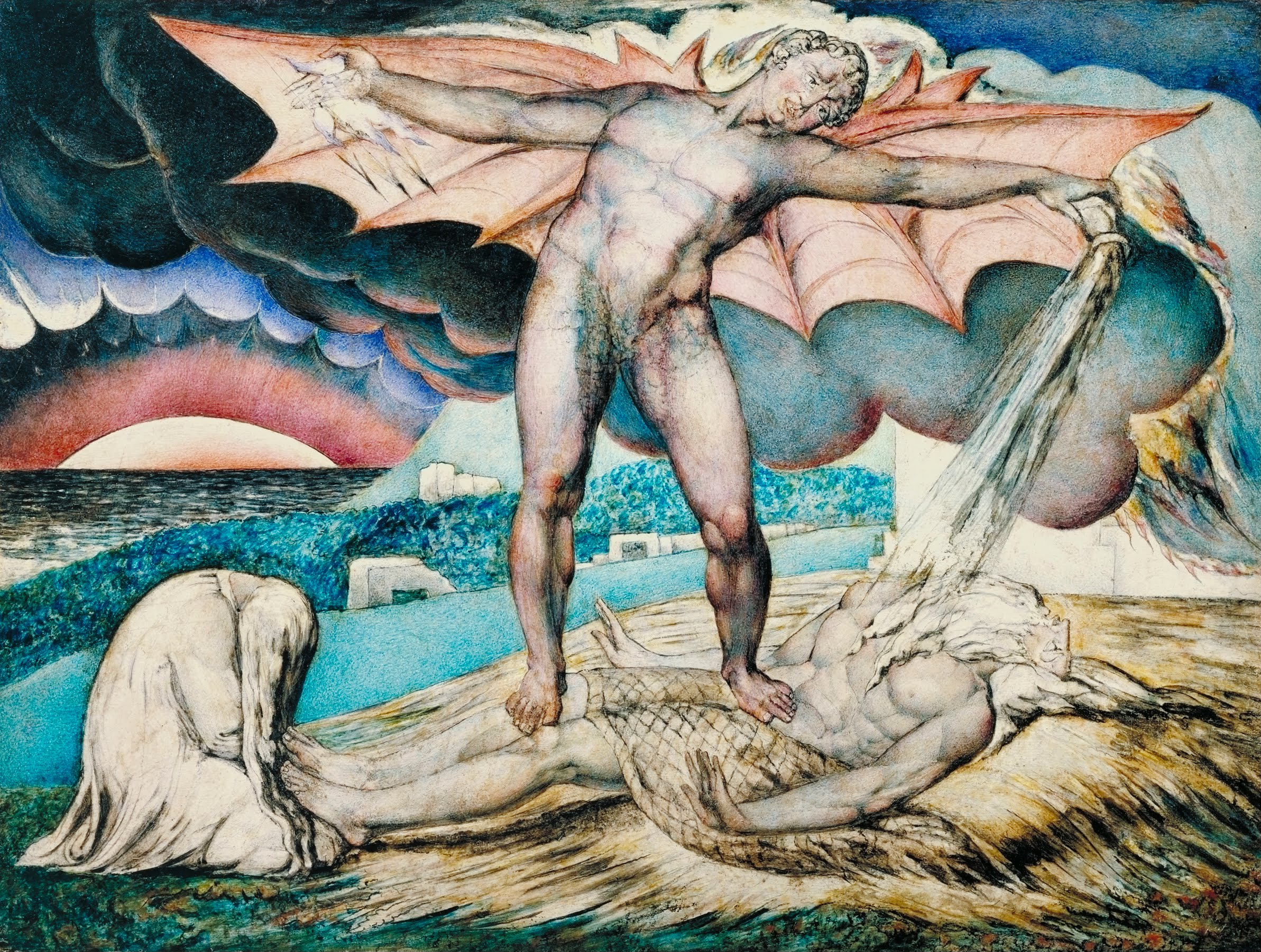

I shall connect, as it were, John Calvin’s analysis of what he observed to be our ingrained penchant for idolatry with relevant deconstructionist analysis of textual language as problematic in continental “theory” of the past sixty years, and then with the biblical presentation of the threat posed by the demonic to evangelism in particular, and to embrace of the communicated “Word” generally – with Paul Tillich’s philosophical theological reflections on the “demonic” as it relates intimately to the “divine.”

And then, in moving to a conclusion, I will suggest the usefulness of dialogue with relevant poetries especially that of W.H. Auden where it plays inevitably with the demonic in pursuit of the divine – for more than ever this is a time when the religious imagination will benefit from dialoguing with the literary.

These sources will help to suggest the relevance of a hermeneutic which counters uncritically “literal” interpretations of scripture and creed, but also, and fundamentally, which must question the vexed term “belief” itself as the appropriate method of expressing commitment to the meaning of biblical narratives, teachings, and subsequent creedal formulations echoed in personal and public expression. I will suggest that people of faith should consider discarding our uncritical use of “believing” and “belief,” and rather instead “play” the propositional, figurative language of biblical Christianity, in recognition that within this language we meet the continuing threat of the demonic at play with us for its destructive ends not ours.

(One of the demonic – or the mythic “Devil’s” – most successful accomplishments is to have used against the faithful the secular, skeptical assumption that this demonic is no longer relevant. Another is to have influenced people of faith uncritically to understand by “belief” what secular scientific rationalism understands by it as “foundational,” to the modern mind.) We cannot “beat” the mythical Devil (the demonic) in pursuit and expression of faith without first acknowledging the ongoing existential threat of the demonic.

I offer a hermeneutic not for those inclined to what fundamentalists and atheists alike appear determined to assume, namely the strictly post-Cartesian, foundational rational-empirical sense of the “literal.” What follows is for those of us wanting to persist in the faith, well-educated in the damaging effects of “rational” secular inquiry[2] or simply grappling for a means of embracing religious “truth.”

By faith I mean here the alternative, subjective, existential sense of foundational personal vision inspired by biblical Christianity. I draw upon inspiring sources which might well appear otherwise unrelated.

The path toward my concluding proposal of a better way to interpret scripture as well as formal religious language generally is indeed experimental and exploratory: interdisciplinary. It will lead to a challenging suggestion that an appropriate new theory of biblical interpretation should now seriously reconsider the modern concept of “belief” (if not the pre-modern “credo”) as hopelessly mired in a secular, positivist rationalism fatally at odds with the communication and embrace of biblical Christianity.

Note this first: previous contributors to the enterprise of hermeneutics would seem to agree that such reflection can be generally differentiated into a hermeneutics of faith and a hermeneutics of suspicion. For this writer, there can be no escape from the hermeneutical circle informing what amounts ultimately to acknowledging a faithful, apologetic purpose: what scripture and traditional religious language responding to scripture generally “mean,” at least for me, is affirmed in an abiding presumption.

The question for this writer is not what a scriptural passage means in personal truth (or for appropriate response in “doing the Word” as a person of motivating faith) so much as how does or can it hold decisive existential meaning when such “truth” is so easily rejected as subjective delusion by our reigning cultural skepticism? The writer is a person of faith who presupposes, as do many others, the highest order of truth in the Christian message “revealed” in the Christian Gospel.

The question addressed in what follows is how can we be captured and re-captured existentially by Scriptural “truth” when we inhabit a thoroughgoingly secular, skeptical age? This “how” requires tenacious examination and may well, of course, frustrate even those of favouring pre-disposition and intent. No one can offer proof (as we currently understand “proof”) of the “truth” of this or any other great religion adequate to meet the skeptical demands of the age. So, the question of a fruitful, effective hermeneutical method, adhering to the tradition of faith as well as to the circumstances of present day cultural understanding, is paramount.

I.

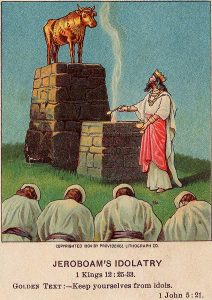

I take enabling encouragement for a hermeneutic of play (and for the side-stepping of “belief,” but more of this below) from an extraordinary observation offered by the founder of my Reform Church tradition. It perhaps will not shock and may indeed enlighten and inspire the reader to be reminded that John Calvin in the ponderous Institutes of the Christian Religion offers us this elegant and liberating observation, “postmodern” in its prophetic implications: “The mind is a continuous idol-making factory.” (Unde colligere licet hominis ingenium perptuam, ut ita loquar, esse idolorum fabricum.[3])

This is one of the more disturbing or perhaps appetizing of the implications he draws from his unrelenting fundamental primary doctrine of Original Sin. “Belief” as employed by secularized religious moderns will forever linger under the permanent threat of damaging idolatrous misuse and meaning. A timely hermeneutic must now pursue the implications and the opportunities for corrective revision of inappropriate interpretations subservient to what has become of “belief,” thanks largely to the prestige of modern science, in our time.

To pursue this further, Calvin observes that we naturally, mindfully, draw idolatrous conclusions and form idolatrous perceptions when it comes to religious or any other belief, but for him especially religious belief. We are formed, as sons and daughters of the original sinners, Adam and Eve, to fall naturally into idolatry as a consequence of inheriting our fallen identity as human beings.

What particular force or power ensures this state of things? The power of the demonic, the deceiving and destroying force built into Creation. Idolatry is of the mythic Devil’s game, which he, the personified demonic, plays skilfully as he goes to and fro in the earth, in history, in our time now as well as in biblical times. Human intelligence, regardless whether “saved” by the grace of the all-powerful God, no matter how learned in the world’s terms, is nonetheless subject to the skilled deceptions of the demonic powers present in the world. To ignore this situation, as for Calvin’s Reformed tradition “ever reforming,” is to ignore whatever we may now mean, if we regard it at all in a secular age, by “damnation.”

But, here, an additional caution must be raised. Calvin exempted writings of canonized scripture from threat of idolatry, in their origin and delivered down through centuries, inasmuch as the Holy Spirit is understood by his seventeenth-century faith to have guided not only their writers, redactors, and translators but the committees which later canonized them. We, however, cannot and should not agree with this exemption, despite that we do agree that in some decisive way these scriptural texts are indeed divinely “inspired.”

What we now know, four centuries after Calvin, from historical-critical interrogation of scriptural texts over many generations, suggests that we should complicate any simplistic understanding of “divine inspiration.” We need to re-think this essential tenet of our faith, in part for the way in which it has come to permit, uncritically for so many Christians, a latter-day secular understanding of the “literal” meanings of scripture to triumph over meaning expressed in the very different hermeneutical context of pre-modernity – centuries before the emergence of scientific method as we know it now.

Modern “literal” interpretations have opened the way to rabid demonic exploitation of idolatry – threatening harmful scriptural misinterpretation. Recent historical-critical grappling with the formation and transmission of the biblical texts – note especially the work of the biblical scholars gathered in the controversial Jesus Seminar in recent years – suggests that politicized scriptural texts, along with texts of all other varieties, should now be approached, too, as writings which in origin and in subsequent reception, faced then and face now the threat of idolatrous misunderstanding.

The writing and reading of religious, even “inspired” religious texts remains circumscribed by fallen human intelligence, as well as fallen human spirit and will. This is to take nothing away from the certain faith, when given, that Scripture contains the inspiring Word of God. Rather, it is to caution Christians, present and prospective, to exercise caution and perhaps agility, too, in the reading and interpretation of Scripture. We must rely finally on the hope of true understanding as offered only by the grace of God. And so “divine inspiration” must be re-theorized, ultimately on an individual basis, to meet this threat as it applies even to scriptural texts.

Idolatry in Christian history has, of course, been a subject addressed again and again, ostensibly always to serve the purpose of sustaining the biblical Christian vision and protecting it from misinterpretation and abuse. Of the many such instances that could be lifted up for note here in support of a timely anti-idolatry hermeneutic, one very recent is to be found in James Woods’ New Yorker review of Terry Eagleton’s criticism of the “new atheist” phenomenon addressed in Reason, Faith and Revolution: Reflections on the God Debate (2009).

Idolatry in Christian history has, of course, been a subject addressed again and again, ostensibly always to serve the purpose of sustaining the biblical Christian vision and protecting it from misinterpretation and abuse. Of the many such instances that could be lifted up for note here in support of a timely anti-idolatry hermeneutic, one very recent is to be found in James Woods’ New Yorker review of Terry Eagleton’s criticism of the “new atheist” phenomenon addressed in Reason, Faith and Revolution: Reflections on the God Debate (2009).

Wood, in referring to the blame for anti-semitism in Christinity cast upon the “idolatries of the man-God” by Theodore Adorno and Max Hockheimer in their Dialectic of Enlightenment, and to Eagleton’s attempt to counter Richard Dawkins and Christopher Hitchens with a Roman Catholic, “Thomistic God” hardly incarnate at all, concludes, “But Christianity is a form of idolatry.” Without elaborating he concludes, re. Adorno and Hockheimer, that “For them, the Incarnation brings the absolute closer to the finite, and makes the finite absolute; it turns spirit into fleshly magic.” And, for support of this rhetorical perspective, Wood reminds us that in another recent book, Saving God (2009), Mark Johnson contends that most religious belief is in fact idolatrous.

If not unavoidable, even the Incarnation is nonetheless critically susceptible to idolatry. And Wood finds himself in agreement with Johnson’s observation that “idolatry is a natural human impulse.”[4] Calvin would agree. The demonic, as I shall argue below, remains permanently in business taking advantage of this situation.

II.

But, first, this reminder of the arguably prophetic dimension of recent “deconstructionist” theorizing – as it relates to my proposal. If no longer quite as arresting, but as intellectually challenging today as it was in the 1960’s, 1970’s, and 1980’s, the “deconstructionist” movement that accompanied and followed the so-called “linguistic turn” toward language interrogation and analysis in analytic philosophy has produced theorizing that bears upon the construction of a new, more relevant, more promising biblical hermeneutic.

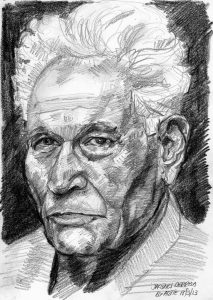

I respect those scholar-theorists who have worked hard to assimilate, whether they agreed with each other or not, the intent and achievement of one contributor to the linguistic, deconstructionist discussion in particular, Jacques Derrida. I have fathomed the intentional difficulty of Derrida just enough to cherish respect for his earlier, controversial work especially. But I am no obsequious follower of his or of any of the innovative great philosophers from whom he derived influence, e.g., Friedrich Nietszche, Martin Heidegger, Edmund Husserl, Ferdinand de Saussure, and Hans-Georg Gadamer. Nor am I versed in the variously focussed subsequent literatures of deconstruction well enough to carry out my own interpretive summary and judgment of the initiatives and achievements that comprise them.

I wish only to draw fleeting attention here to those aspects of Derrida’s methods and apparent goals that would seem not only to echo but possibly even to support my hermeneutic suggestion that a person of persisting or would-be genuine faith should consider what amounts to a kind of gaming of religious texts, starting with Scripture, and to do so in order to, consciously and conscientiously, out-maneuver our putative natural human tendency to idolatry – with the help of the invoked grace of God.

The deconstructive philosophers and their sympathetic followers, to my knowledge, did not apply their language analyses directly to Scripture or other derived religious writings. They refrained, it would seem, as focussed academic philosophers, having enough on their plates in the way of problematizing philosophical texts to not want to open further battle lines with traditional religionists. But their studied critiques, Derrida’s most especially, were directed at writing, at “discourse” generally, if especially of course at the writings of academic philosophy, of literature, and of the “human sciences” generally.

When Derrida writes, “… language bears within itself the necessity of its own critique,”[5] one might imagine that he includes religious writings under this apparently comprehensive rubric. But, if toward the end of his career he addressed the issue of religion directly and to pallid effect (see below), as a younger man in the 1960’s and 1970’s he apparently did not, concentrating as surely he thought he must, on his work as a philosopher hoping to awaken his profession to the deception and danger of allowing “monologisms” (systems of projected coherence) everywhere implied but unspoken in language, in “discourse,” to remain unchallenged.

But to establish my frame of reference here, note that religious language is employed by people of faith in a way different from how they, apart from their faith, and of course the non-religious employ the language of the secularist, post-Enlightenment world view influenced by science and analytical, rational-empirical philosophy. The “truths” of religious faith are not of the same order as the “truths” determined and sought by “enlightened, rational” reason through the procedures of scientific method upon which moderns habitually confer overwhelming prestige. The modern (and post-modern) religious have Ludwig Wittgenstein to thank for helping us to recognize, if we are willing epistemologically, and then, if compelled, to embrace religious talk and religious writing as ordered by the “rules” of a different but equally human language “game” than by those of the secularist “game” played by science.[6]

Wittgenstein’s “game” is an important, nicely suggestive term for the sort of worship, prayer, and discussion language commonly employed within historical communities of religious faith. “Game” suggests “play,” and it is the “play” of and within all language as theorized by deconstructionist, postmodern continental philosophers and their followers which I will here invite for consideration into this experiment in hermeneutics, applying it especially to religious language. In the early Derrida and the inheritors of his multi-question-begging theory of the playful, undecidable differance to be addressed primarily in written texts we meet a considerable source for a more insightful hermeneutic.

Derrida’s early deconstructionist writings on language and the logocentric tendency, taken as intrinsic to metaphysics, to reduce (and perhaps betray) all writing to a stable meaning have attracted and frustrated general readers, literary critics, and philosophers since the 1950s. Inspired to his own kind of creativity as a scholar by Nietszche, Heidegger, and Saussure, among others, Derrida is perhaps most famously known for his attribution of both “difference” and, especially, “differance” (as in “to defer” in English) to textual language, in effect attributing to language, especially to language employed by the philosopher naively pursuing fixed truths, effectively an endless undecidability of meaning.

At the heart of this analysis, of course, lies the observation that there can be no self-evident, one-to-one link between “signifier” and “signified.” For, as in Saussure before him, language is to be understood as a “differential” network of inconclusive meanings. For Derrida this applies to writing, to texts, more than it does to speech. Thus, an inherent effect of textual language, no matter how clearly it is employed by philosophers, unintended and unrecognized, is disruption of any apparent meaning conveyed. Language as it deflects and complicates a philosopher’s intended use of it, through the inevitable elements of metaphor and other suggestive figurative devices, ensures that philosophy texts, when deeply engaged, pose literally endless problems of interpretation.

For Derrida, running so deep in Western thought that they respect none of the conventional boundaries, lie paradoxes of meaning produced not just in philosophy but across all varieties of discourse.[7] Textual language, in short, has been presented to us by Derrida and his followers as inherently mischievous – that is, inherently tending to make mischief with the message that a writer labors to convey.[8]

And so, readers of philosophical texts have been warned by this Derridean cadre of linguistic theorists not to place innocent trust in the clarity and precision of the language that writers have duly chosen to convey their message and meaning. Writers will do their best in writing to capture and communicate meaning. But then readers must struggle both with and against the resulting texts to derive what provisional individual meaning possible but never a finally established meaning. This difficulty newly identified by Derrida extends beyond the long-recognized challenge to writers to take into strategizing consideration, as they must, the knowable etymology of words they employ as evolved to the moment of their writing.

I emphasize my drawing upon the early Derrida, for the later Derrida addressed religious issues, as in the collected essays in Acts of Religion (2002) [9] But he does not in those later essays employ the language theory of “differance,” at least not in the influential way that he did in earlier writings. Nor does the later nor the early Derrida treat the language of scripture or of creed and prayer when he addresses the language of “monologic,” “logocentric” philosophy.

The time has come to explore the consequences of submitting religious language as such to the possible usefulness of Derrida’s critique. For we should now acknowledge that even and especially the language of Scripture can and should be read as inherently, if not intentionally of course, mischievous. Its language, otherwise privileged by divine inspiration, should be regarded as hardly different despite its authority as “inspired” writing, from the monologic philosophical language Derrida analyzes. As we move beyond Calvin’s conferral of exemption upon scriptural language, we move beyond Derrida’s effective decision not to submit scriptural language to the innovative critique with which he treated philosophical “discourse.” We do so to take a further step toward the experimental hermeneutic we propose below.

I borrow here for my purposes Derrida’s use of “difference,” which his expert interpreter, Christopher Norris, summarizes thus: “Writing is the endless displacement of meaning which both governs language and places it forever beyond the reach of a stable, self-authenticating knowledge.” Because of the imputed differing “difference” (between signified and signifier) of Derrida’s, the reader cannot hope to escape or to overcome the “snares of textuality,” that is, of language endlessly deferring its meaning or meanings. “Differance” perpetually sets up, as Norris puts it, following Derrida, “a disturbance at the level of the signifier.” As a result, sense must remain “suspended between the two French verbs “to differ” and to “defer,” both of which contribute textual force in a passage of writing, but neither of which can fully capture its meaning.”[10]

We must contend, to put it differently, with a conception of language as an endless play of signifiers in contrast to the logic and force of fixed “transcendental” signifiers. The problem is compounded in translated texts; as Derrida writes in the essay Positions,

for the notion of translation of one language by another we would have to substitute a notion of transformation: a regulated transformation of one language by another, of one text by another. We will never have, and in fact have never had, any ‘transfer’ of pure signifieds.[11]

We should now apply this to scriptural texts.

The early Derrida famously objected to any response that he might be offering another system of interpretation following preceding systems. He objected to any suggestion that in his critical writing one could detect an “essence” of strategy. Sympathetic critical readers credit him with pursuing a new and entirely different mode of thinking instead of simply moving to new thoughts within inherited categories supporting inherited systems. His deconstructionist project is intimately tied to the respective texts interrogated, for as Christopher Norris notes, his project “can never set up independently as a self-enclosed system of operative concepts,” and it resists strenuously “any kind of settled or definitive meaning.”[12] Derrida objected playfully, to being “understood.”

The relevance of Derrida to an exploratory biblical hermeneutic is suggested whenever he refers to the “transcendental signified,” in other words, to a central or unifying concept independent of language which is to be found, as he observed, throughout the history of metaphysics. This is what metaphysics has historically sought, a “transcendental signified” (or “presence”) independent of language. But, as Derrida wants to show, the language of metaphysics (or of philosophy generally, and, ultimately, all discourse) deflects or complicates in several possible ways this project.

Whether a mere projection or a brilliant insight on Derrida’s part, he gives us a forceful approach to historical or current texts based on the reminder, as Norris sums it, that “There is no language so vigilant or self-aware that it can effectively escape the conditions placed upon thought by its own pre-history and ruling metaphysic.”[13] No Derridean deconstructionist ally that I know of has wanted to apply this conclusion and its consequences to religious texts starting with Scripture itself. But now we should, as it will help in the formulation of a timely biblical hermeneutic.

Divinely inspired texts, and of course doctrinal and confessional formulations as well as liturgical language derived from the faith instilled by these texts, nonetheless for being “divinely inspired” do remain texts created and then translated and edited in historical time by historical writers.[14] Derrida argues that philosophers have been able to impose their various systems of thought only by ignoring, or certainly suppressing the disruptive effects of language.[15] The cherished belief that scriptural texts are divinely inspired has made it all the easier for persons of faith to ignore Derrida’s “disruptive effects of language” – to the detriment of the actual inspiring Word.

Specifically, the element of his analysis, which should be applied in a new hermeneutic begins with, or at least fundamentally includes the notion that all writing effectively presents a “free play” of undecidability within every system of communication, every discourse. To quote Norris again, the operations of writing “are precisely those which escape the self-consciousness of speech and its deluded sense of the mastery of concept over language.”[16] By this reckoning, in all writing, in all texts, the assumed and trusted connection between signifier (language) and signified (any and all referents including the “transcendental signified”) has been shown to be problematized at best and deceiving at worst.

Specifically, the element of his analysis, which should be applied in a new hermeneutic begins with, or at least fundamentally includes the notion that all writing effectively presents a “free play” of undecidability within every system of communication, every discourse. To quote Norris again, the operations of writing “are precisely those which escape the self-consciousness of speech and its deluded sense of the mastery of concept over language.”[16] By this reckoning, in all writing, in all texts, the assumed and trusted connection between signifier (language) and signified (any and all referents including the “transcendental signified”) has been shown to be problematized at best and deceiving at worst.

So, the response to this situation, argues Derrida, is to acknowledge that finite language is in effect a field of “play” – to quote him, “a field of infinite substitutions because it is finite … [and] there is something missing from it: a center which arrests and grounds the play of substitutions.” By “play” then, Derrida appears to mean that in reading one must recognize and respond as he or she will to the de-stabilized and de-stabilizing condition inherent in the signifying language. Play, or “free play,” is required because all written content lacks definitive meaning, and thus the adequate communication of information intended by the writer can never be assured.

At risk of complicating this facet of Derrida’s theory that I find especially relevant, I note his additional observation: “The overabundance of the signifier, it supplementary character, is thus the result of a finitude, that is to say, the result of a lack which must be supplemented.“[17] No meaning of a term is fixed, rendering definitive definition effectively impossible. So, every term necessarily requires a supplement or supplements, something or some things which help it exist and be understood.

Thus, the view of historical language or “discourse” as inherently destabilized leads to the need in reading to understand the consequent need for careful, reflective but never decisive playfulness in order to receive as much of the intended meaning of the text as possible, realizing that one can never reach anything but one’s own limited, “supplementary” reading. Of the two kinds of interpretation Derrida posits in “Structure, Sign, and Play,” one dreams of deciphering a fixed truth, and the other, more appropriate, and I quote Culler here, “…affirms play and tries to pass beyond man and humanism, the name of man being the name of that being who, throughout the history of metaphysics and of onto-theology – in other words throughout his entire history – has dreamed of full presence, of reassuring foundation, of the origin and end of play.”[18] The bequiling term Derrida employs, as noted above, to suggest this inescapable difficulty is Differance.

For our purpose, and because of this imputed undecidability within language in any system of communication, this skeptical view can lend support to Calvin’s rather harsh diagnosis of the condition of human conciousness, that we cannot help but function as each one of us a “continual idol-making factory.” We struggle to detect and to express the truth. But we are so often misguided in our occasional belief that we have found and can communicate divine truth. Divine inspiration does not automatically overcome this problem; for the Word comes to us not in but mysteriously through the written, translated, edited words. We are congenitally victims of effectively idolatrous language in which the signified is confused with the transcendental signifier, in which that which can only be symbolized (the divine) is confused with the symbol itself.

Ambiguity is our fate, and as Timothy Beal noted in a recent The Chronicle Review article, “The Bible Is Dead; Long Live the Bible,”[19] “Ambiguity is the Devil’s playground.” Let us adapt the often confusing, complicated language theories of Derrida’s deconstructionist project as effectively supportive of Calvin’s anti-sacramental, prophetic theology and our experimental hermeneutic. And we turn to a neglected, fairly recent philosophical theology of the demonic for a nicely related additional source upon which to build our hermeneutic.

Kevin Lewis is a professor of Religious Studies in the Department of Languages, Literatures, and Cultures at the University of South Carolina. Lewis graduated from the University of Chicago with a PhD in Religion and Literature in 1980 and published The Appeal of Muggletonianism in 1986. He has given papers on various dimensions of the Muggletonian tradition to the Carolinas Symposium on British Studies, the Southeastern section of American Academy of Religion, the Southeastern Nineteenth-Century Studies Association, and the local Columbia Metaphysicals.

[1] David Jasper’s term in A Short Introduction to Hermeneutics (Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2004), a useful primer. Also helpful is David Klemm’s collections, Hermeneutical Inquiry: Vol I, The Interpretation of Texts and Vol II, The Interpretation of Existence (Atlanta, Scholars Press, 1986; eds. Charles Hardwick and David Duke, for the American Academy of Religion, Nos. 43 and 44 – for the evolution of such reflection over the past two centuriues. See also Patrick Sherry, Religion, Truth, and Language-Games (London, Macmillan, 1977) and John D. Caputo, Radical Hermeneutics: Repetition, Deconstruction, and the Hermeneutical Project (1987), followed byMore Radical hermeneutics: On Not Knowing Who We Are (2000), both published by the Indiana University Press. And of course cf. Paul Ricoeur in many publications over his career.

[2] See especially Robert Bellah, Beyond Belief: Essays in Religion in a Post-Traditional World (New York: Harper & Row, 1970) and Charles Taylor, A Secular Age (Harvard University Press, 2007).

[3] Latin edition, 1559, Vol. I, ii, viii.

[4] James Wood, “God in the Quad,” New Yorker (August 31, 2009), 75-79

[5] Jacques Derrida, “Structure, Sign, and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences,” in Writing and Difference, tr. Alan Bass (London: Routledge, 1980), 284.

[6] Ludwig Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations, tr. G.E.M. Anscombe, 1953 (Prentice Hall, 1999).

[7] Christopher Norris, Deconstruction, 3rd ed. (London: Routledge, 2002), 21.

[8] To borrow a somewhat similar supporting perception from Hans Georg Gadamer, for whom, as he argues, texts cannot have intrinsic meaning, we can never confidently recover or discern an author’s intent in a text. For the mischief inherent in all language, especially in that of “truth”-pursuing philosophical texts, prevents it. So the reader ultimately cannot hope to understand a text in order to apply it. Rather, he or she can only hope to apply it in order to give it personal understanding. See Truth and Method, 2nd revised ed., tr. Joel Weisheimer and Donald Marshall (New York: Crossroad, 2004.

[9] Jacques Derrida, Acts of Religion, ed. with Introduction by Gil Anidjar (New York:Routledge, 2002).

[10] Norris, Deconstruction, 32.

[11] Derrida, Positions, tr. Alan Bass (University of Chicago Press, 1981), 31; quoted in Alan Bass’s “Translator’s Introduction”, Writing and Difference (London: Routledge, 1978), xv.

[12] Norris, Deconstruction, 31.

[13] Norris, Deconstruction, 22.

[14] Contrast, of course, the evolving critical approach to the texts of the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament with the binding traditional Islamic teaching that the Qu’ran was composed in heaven in Arabic by Allah and delivered piecemeal directly to Prophet Muhammed over several years.

[15] Norris, Deconstruction, 18.

[16] Ibid, 28

[17] Derrida, “Structure Sign and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences,” Writing and Difference (London: Routledge, 1978), 289, 290.

[18] Jonathan Culler, On Deconstruction: Theory and Criticism after Deconstruction (Cornell University Press, 1982), 131.

[19] Timothy Beal, “The Bible is Dead; Long Live the Bible,” The Chronicle Review (April 17, 2011).