The following is the second part in a two-part installment. The first part can be found here.

III.

We proceed first by a reminder of Scripture itself (which makes no claim to be taken “literally”) and, specifically, of the references to the demonic (the Devil, Satan, Beelzebub) scattered through the Synoptics, the Pauline letters, and Revelation – remembering, of course, the serpent’s role in the drama of the Garden of Eden, and the power ascribed to Yahweh’s familiar, Satan, in Job – a power and authority accumulated “from going to and fro in the earth.”

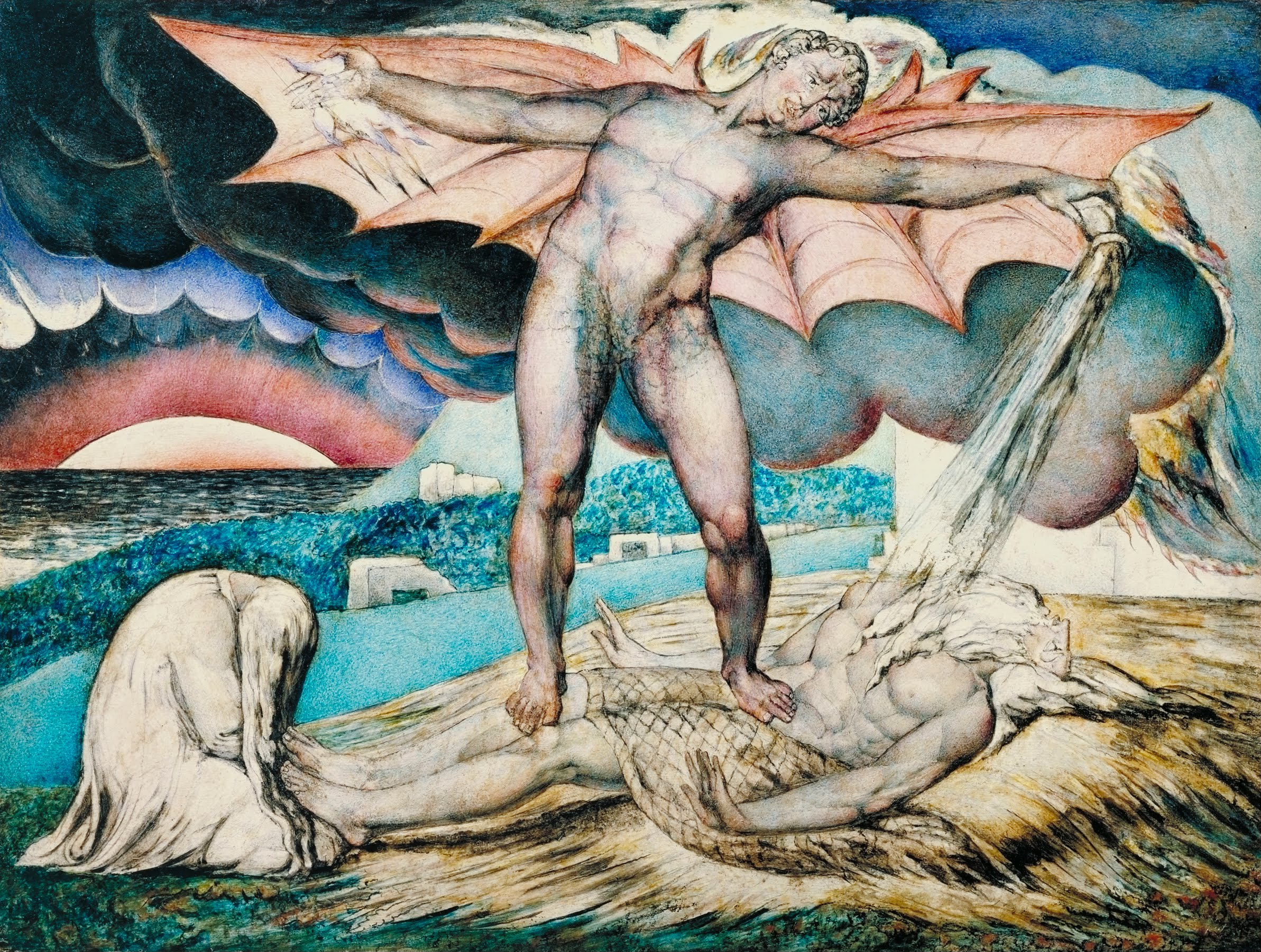

We turn to Scripture to recall the biblical demonic in its considerable appearances. In the New Testament, as in the Old, the demonic is personified in the figure variously named Satan, the Devil, Beelzebub, and occasionally broken out into the company of demons generally. Much has been written by historian critics about the evolution of the “Devil” as concept and figure, and we need not linger here on subsequent treatment accorded this depraved mythic figure all the more threatening because he possesses our worst human characteristics in the extreme. Matthew gives us the fullest picture of the mano a mano temptation of Jesus in the wilderness (4:1-11), followed by the analogy of the sower of weeds whose purpose is to defeat the “good seed” (13:36-40).

In Mark 4:14,15 we meet a Satan who immediately steals the saving “word” sown in audiences by Jesus. Here in Mark, as elsewhere the demonic is associated typically with the “things of man” (8:33), as in John we are referred to the Devil as “the ruler of this world” (12:31). Paul in Acts 5:3 receives his conversion mandate to help willing listeners be delivered from the “power of Satan” (26:18). Paul warns the Corinthians to guard lest they be “outwitted by Satan, for we are not ignorant of his designs” (IICor. 2:11). And then he is figured as the malevolent “god of this world,” metaphorically blinding the minds of unbelievers to keep them from seeing the light of the Gospel (IICor. 4:4). For the sake of Jesus as the Christ, Paul tells us, he embraces the “thorn in his flesh” given by a messenger of Satan – for the good of his evangelizing mission (an example, I suggest, of strategic “playing” the Devil for the good of that mission [IICor. 12:7-10]).

In his second letter to the Thessalonians, he warns that the second coming awaits the revealing of the “son of destruction” who falsely proclaims himself to be God, with wicked deception empowered by the “activity of Satan” (2:1-11). In James 3:15 we are warned of “earthly demonic” wisdom, and in I John 2:14 readers are praised for having successfully overcome “the evil one.” Then in I Timothy 5:15 readers are cautioned against “straying after Satan.”

Among the references to the power and designs of the demonic, threatening the spread of the Word, of course we meet in Revelation reference to “the deep things of Satan” – his threatening work is not simple, not easily confronted (2:24). The text that inspired Paradise Lost, Rev. 7-12, gives us the heavenly defeat of “the dragon and his angels” by archangel Michael and his company, his throwing down to earth where subsequently, in anger, the “ancient serpent who is the devil and Satan” will play his deceit and destruction while he may, until bound finally in the bottomless pit until released if only for a little while at the end of the thousand years predicted in Rev. 20: 2,3.[1]

The canny reader of Scripture and creed, as Martin Luther reminds us in his booming “A Mighty Fortress,” though attacked by temptation to misadventurous interpretation, must know how to keep the revealed God on his side:

And though this world, with devils filled, should threaten to undo us,

We will not fear, for God hath willed his truth to triumph through us:

The Prince of Darkness grim, we tremble not for him;

His rage we can endure, for lo, his doom is sure,

One little word shall fell him.

That “little word” must be discerning, in the hope of enabling grace.

We will profit here by re-examining the power and authority ascribed to the traditional demonic as it was recovered from neglect by influential previous theologians and interpreted for our time by Paul Tillich, suggesting, I propose, a heretofore unremarked affinity with Calvin’s picture of the “idol-making factory” threatening within each of us.

The “Protestant Principle” as interpreted by Tillich and of course many others in this tradition, we are reminded, most generally combines conviction of faith with careful, tentativeness of reading or expression. “Tentative” here, as we shall argue below can be interpreted further as a need for playfulness, that is, for intentional, individualized gaming of the inherent idolatrous tendency in human nature or the mind itself – echoing usefully Ludwig Wittgenstein’s observation, noted above, that religious language, written or spoken, should be taken as but one in a repertoire of language “games.”

Tillich was perhaps the one great Protestant theologian in the last century who, upon reflection, determined that, given as he saw it the fundamental ambiguity of the human condition, and in the belief in original sin, in order to ensure the divinity of the Divine Creator, people of faith must acknowledge in their lives the contrary presence of the demonic. Tillich went to great length in The Interpretation of History (1936)[2] to plead for recognition and appropriate apprehension of the demonic understood existentially, “abstractly” rather than, metaphorically, through the person of the cartoon Devil of popular culture.

Without belief in an adversarial, evil-intending demonic force tempting the faithful to commit a particular idolatry understood as worship of the religious symbol rather than that which the symbol symbolizes, Tillich reckoned that the faithful, despite otherwise favourable appearances, will miss if not effectively betray the very divinity (God) they purport to worship and obey. His theological purpose was to encourage in the faithful an unrelenting self-criticism lest the intrusion of the demonic prevent us from grasping and being grasped by the God beyond the constructed images that conventionally express God.

Tillich’s persistent warning of this kind should fall on fertile ground in those, this writer among them, brought up in the Reform tradition. Putting aside the sometimes painful struggle with John Calvin’s over-riding concern for the great distance from his creatures of the Christian God, and with his perhaps over-bearing doctrine of Original Sin, we will note how Tillich, in his own way, drawing upon many precedent theological and philosophical writers, would seem to echo Calvin’s observation, quoted above, concerning the “idol-making factory” with which we are born and somehow must make our peace.

Tillich’s persistent warning of this kind should fall on fertile ground in those, this writer among them, brought up in the Reform tradition. Putting aside the sometimes painful struggle with John Calvin’s over-riding concern for the great distance from his creatures of the Christian God, and with his perhaps over-bearing doctrine of Original Sin, we will note how Tillich, in his own way, drawing upon many precedent theological and philosophical writers, would seem to echo Calvin’s observation, quoted above, concerning the “idol-making factory” with which we are born and somehow must make our peace.

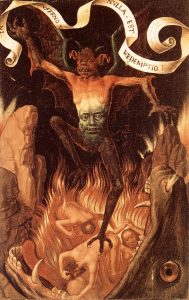

Having noted the theme of the demonic in 1936, to which I will return below, note first how he touches upon it in the later, better known The Protestant Era (1948) and his Systematic Theology, Vol I (1951) He had complained in The Protestant Era that the demonic had become obsolete in contemporary theology, and recommended that its “abuse” in the Middle Ages (the cartoon figure of the Devil) should “not forbid right use.” For, as he observed, we meet in the center of Luther’s as well as Paul’s experience “the structural, and therefore inescapable, power of evil” which should inform exploration of the “structural character of evil in our period.”[3]

Tillich, of course, developed this thinking from influence by precedent figures, Duns Scotus, Luther, Jacob Boehme, and Friedrich Schelling, his dissertation subject. From this tradition Tillich took the impetus for advocating the “demonic depth in the divine nature itself,” giving it dialectical treatment – a reiterated theme in the lecture courses of his in which I enrolled as a Harvard undergraduate in the 1960s.

In order to plead “the structural character of evil in our period,” all the more threatening for our habit of ignoring it, Tillich linked the demonic with the countering and ultimately triumphant “divine structure, … the Gestalt of grace.” It is through grace that we must be grasped by the divine to achieve a personal faith in which the continuing demonic threat is defeated. But he insisted that we acknowledge and then combat “the demonic in the divine nature itself.” (my italics)[4]

In short, the demonic potential in the divine is structural, and it carries the potential to conquer the divine, in history if not eternally. Tillich made much of the concept of “ecstatic” reception of divine grace. For him, historically it has been ecstatic experience through which the transcendent divine is revealed, as it were, “grasping” the individual into true faith. But Tillich acknowledges that the demonic also can and does take possession of the individual. At the same time he insists upon a decisive difference of quality and character: “…while demonic possession destroys the rational structure of the mind, divine ecstasy preserves and elevates it, although transcending it.”[5]

In the original 1926 essay, “The Demonic,” included as a long Chapter Three in The Interpretation of History, then in better translation by Garrett Paul in 1989, Tillich’s acknowledged purpose is to “strengthen the prophetic spirit of our era.” He observes that the term demonic, “when it has not degenerated into an empty cliché, always retains this meaning: the unity of form-creating and form-destroying power.” The demonic, as fundamentally linked to the divine, combines destructiveness with creative form in a defining dialectic.

As an aside, Tillich warns that in “starkly religious times” the demonic becomes so closely tied to the non-dialectical, merely negative figure of Satan that, in the process, in losing its power of creation, it becomes an “unreal concept.” We must grasp the metaphysical essence of the demonic, that is, the grounding of the destructiveness in form, in the “ground of being,” that ultimate “depth” “where ‘being’ is an expression for the unconditional, transcendent mystery beyond which thought cannot go, because thought rests upon it.” But then, as he insists, the ground of all being is also an inexhaustible abyss. By this path, putting aside the merely negative mythological figure of Satan, Tillich comes to the conclusion that “the demonic, by way of contrast [to the satanic], always entails the divine, the union of form and destruction of form; that is why the demonic can acquire existence, albeit an existence characterized by tension between the two.”[6]

The argument in this essay is indeed challenging, but along the way we meet recognizable, helpful insights, e.g., the passage which begins “The demonic comes to fulfilment in the spiritual personality.” Those “spiritual” among us have the most to fear from the demonic power as we pose “the primary target of demonic destruction.” The “something else” of the demonic “contains the vital powers within itself, but it is also spiritual – and spirit destroying.”

The presence of the demonic in a person is best indicated when the ego’s disruption manifests an ecstatic, creative character in spite of all its destructiveness, only to be combated successfully by “the state of grace.” For “possession and grace are corresponding states, the demonic and the divine are correlated in their power, [and] both possession and grace exalt the spirit.” But we note: “…where grace unites these powers to the highest form, possession uses them to contradict the highest form.” Tillich accentuates the profound kinship of the demonic and the divine to make his point, that “…it is in the domain of the sacred, the holy, that we find the abyss, the unconditional power that invades our reality.”[7]

The presence of the demonic in a person is best indicated when the ego’s disruption manifests an ecstatic, creative character in spite of all its destructiveness, only to be combated successfully by “the state of grace.” For “possession and grace are corresponding states, the demonic and the divine are correlated in their power, [and] both possession and grace exalt the spirit.” But we note: “…where grace unites these powers to the highest form, possession uses them to contradict the highest form.” Tillich accentuates the profound kinship of the demonic and the divine to make his point, that “…it is in the domain of the sacred, the holy, that we find the abyss, the unconditional power that invades our reality.”[7]

Tillich continues, addressing “the role that the demonic plays in all historical creativity,” and suggesting that all serious historiography should include “the elements of the mythical [the divine, the demonic], else it will never rise above mere description of discrete finite entities.” We must recognize “how every moment [of life, of history] is suspended between the divine and the demonic.” And so all serious interpretation of history must employ “the mythic consciousness, with its insight into the dialectic of the divine and the demonic.”[8] This notion was echoed at a distance by Timothy Beal in a recent issue of The Chronicle Review, where he notes simply that “Ambiguity is the Devil’s playground.”[9]

Our intellectual-cultural situation in the second decade of the twenty-first century, in ever-changing historical flux, suggests, I propose, that we regard carefully Tillich’s perspective on the history of the great religions:

The demonic is the negative and positive presupposition of the history

of religions. All higher, individual, historically oriented religions emerged

from a demonic substratum. It was through their struggle with the demonic

that these religions attained their particular form: the form in which they

exert a compelling power over consciousness, and from which the

demonic element, as their substratum, can never disappear.

We think in only two dimensions, argues Tillich, and in our secular age we cannot or will not see what he calls the “third dimension above and beneath” us, the dimension both divine and demonic, “breaking through form, exalting and corrupting.” Gone, he laments is our fear of old (expressed through myth), reminding us that in the biblical period “one of the chief arguments of the Christian apologists was that Christ had conquered the demons.”

We stand forever as creatures of history “in the midst of the contradiction between the divine and the demonic,” where only careful and constant discernment of this dialectic will enable us as best we can to know or to see the creative-destructive power of the demonic infused in our lives along with the divine.[10] The embrace of this dialectic is not only vital to the interest of Christian religion and all of humanity, but suggestive of our need of a responsive new biblical hermeneutic.

IV. Conclusion

Recognition of the demonic as structured within and against the divine, of the threat of idolatry ingrained permanently in the mind even and especially of the faithful, and of the inevitable disruptive mischief in language, even that of Scripture, reckoned by the “linguistic turn,” calls for an innovative response in hermeneutical reflection of the moment. An adequate response by a hermeneutics of faith will of necessity incorporate a challenging hermeneutics of suspicion. A profound grasp of the “structured” divine, gathered from the Word of God in Scripture and reinforced by a community of faith, must be complimented – to meet the ever-increasing challenge of present secular cultural circumstances and of faith itself – by a profound grasp of the “structured” demonic. We must be clear about the consequences for theory of biblical interpretation and for the uses we make of creedal, confessional language derived from these recognitions – in individualized personal as well as common experience.

Shifting to the testimony of another writer and poet, here briefly I will note that W.H Auden in the aftermath of his “re-conversion” to Christian faith in the late ‘thirties, when he subsequently wished to invite and to proclaim this faith in the divine into his poetry provides instructive illustration of acknowledging what we now identify as the predicament and the prophetic opportunity launched by theorizing following the “linguistic turn.” In his poetry of the ‘forties, Auden crafts strategy to address the risk perceived in the attempt to embrace the truly sacred, implicitly embracing something like that Calvinist caveat along with the Tillichian insistence on confronting the demonic.

Before Derrida arrives on the scene, Auden proposes a Derrida-like gaming of language in hopes of conveying divine truth. His poetic project of that time would seem to be, in great part, one of protecting as best he can, by means of playful poetic language, his religious testimony from falling into unintended, misdirecting idolatry. He offers, as it were, a timely hermeneutical lesson for people of faith generally. Consider one illustrative passage from Auden’s “New Year Letter,” re. The “Devil” (whom he was to identify as “the father of Poetry” in an accompanying note)[11]:

For he may never tell us lies

But half-truths we can synthesize:

So, hidden in his hocus-pocus,

There lies the gift of double focus,

That magic lamp which looks so dull

And utterly impractical,

Yet, if Aladdin use it right,

Can be a sesame to light.[12]

We remember that Soren Kierkegaard told us, prophetically in the previous century, that “a poet is not an apostle, he casts devils out only by the power of the devil.”[13] Auden at the time of reconversion decided that he would need to understand his poetic practice “as a religious activity” in the vein of Kierkegaard, thence to approach his task as “unpredictable, isolating, and anxiety-ridden.” Thus, with Kierkegaard, Auden understood that the man of talent, even more than the man of wealth, is that “rich man” in the Biblical passage for whom it is so difficult, perhaps near impossible, to enter the Kingdom of Heaven.

It was Reinhold Niebuhr who brought Paul Tillich to Auden’s attention, and, in particular, Tillich on the demonic in The Interpretation of History.[14] For Tillich, artists and intellectuals in modernity who care about the divine must summon all available resources at their command to discern the omnipresent but oh-so-subtle demonic presence and oppose it as they are able. The destructive power of the demonic is always to be found merged, inextricably, with creative, productive energies. Here recall again Calvin’s warning of our innate idol-making tendencies.

The consistently self-conscious strategizing of poetic (and religious) language is a sine qua non for this sort of poetry and – I would add also for discerning, critical conduct of the Protestant faith generally. The conversational, witty address of an Auden must be propelled by a fundamental irony, cosmic in perception, linguistic in expression. The poet’s skill set must include unrelenting self-examination and self-correction (up to but not eventuating, we hope, in paralysis) lest the vulnerable gift of his or her language be allowed to betray the gift of his or her vision. Employing the language of metaphor and symbol, such a poet may well make strategic use of the demonic, especially when the convenient figure of the mythic Devil, traditionally imagined as both deceiver and adversary of the religious, can be employed to identify and confront the threat of idolatry. But more of this literary application in a later essay.

Our major challenge, identified above as the need now to consider replacing in the vocabulary and the minds of people of faith the term “belief,” of course demands further explanation. I proceed knowing full well, of course, that the implementation of such a proposal will be well-nigh impossible for a majority of Christians un-prepossessed by such worrisome self-questioning, so fixed over the centuries has been embrace of “believing” the Word of God in Scripture and incarnated in the person of Jesus as the Christ. It was fixed early by the formulation and adoption of confessional statements comprising the creeds which has helped to unify Christian communities early and late.

Our major challenge, identified above as the need now to consider replacing in the vocabulary and the minds of people of faith the term “belief,” of course demands further explanation. I proceed knowing full well, of course, that the implementation of such a proposal will be well-nigh impossible for a majority of Christians un-prepossessed by such worrisome self-questioning, so fixed over the centuries has been embrace of “believing” the Word of God in Scripture and incarnated in the person of Jesus as the Christ. It was fixed early by the formulation and adoption of confessional statements comprising the creeds which has helped to unify Christian communities early and late.

“Credo” (“I believe”) has been the natural, lead-in to the personal and collective confession of faith for centuries. I proceed knowing full well that already people of faith have for generations projected upon “belief” their own convenient personal meanings. And, of course, in the Fourth Gospel we are told that Jesus as the Christ asks followers not to believe in him exactly but to believe into him (pistue eis, 3:18) opening opportunity for creative interpretations in response.

But clearly “I believe” meant something different in the centuries before the early modern coming of the procedures of natural science to revolutionize the Western intellectual landscape, wherewith the “I believe” of the faithful lost ground upon which to stand (entailing discomfiting qualification and compromise). This is common knowledge, of course, but people of faith still, after centuries of “modernity,” have not made the corrective adjustment if not by discarding “I believe” then by re-theorizing it firmly in a way or ways needed to cope with the prestigious “I believe” of our “enlightened,” rational, sceptical, secular scientific age. We should not question the “I believe” of the faithful in the centuries before the advent of modern science. We cannot know well, from our late vantage point, what it could actually have meant in the pre-modern mind.

That said, however, and in consideration of the newly recognized undecidability in language itself, the faithful now should no longer cherish an “I believe” which no longer can mean what it meant for pre-moderns, and, moreover and to the point, has been decisively, perhaps painfully but also understandably taken over, reduced and effectively deformed by rational-empirical procedures of verification and falsification. To ask of the faithful that we retain traditional usage of “I believe” has increasingly become a demand for unwitting perjury, for a dishonesty nothing like the “scandal” of what was asked of converts and the faithful for centuries before the coming of science and Descartes’ doubt in order to believe. Wittgenstein on language “games” can help here a little but not enough. The problematic “newness of life” now promised to “believing” converts and the faithful cannot resemble the “newness of life” offered before modern science captured and shrivelled to its own purposes the “I believe” of the traditional credo confession.

Following the prophetic advice of James P. Carse in his recent book, The Religious Case Against Belief [15], we should let the rational-empirical, analytical secular (as well as the religious formed permanently and unwittingly in that sort of mind) have their diminished “belief.” But note: slowly but surely modernity has taken it into a permanent Babylonian Captivity. The religious who have broken through this repressive mind to become truly “persons of faith” should let it go to avoid distracting epistemological skirmishes.

The texts of the Christian Bible did not then, in their various origins, and need not now require modern scientific “belief.” As Carse puts it, religion has always transcended the narrow boundaries established by “belief,” which restrict thought, encourage hostility, and risk dangerous, wilful ignorance not sanctioned by great religious vision. The once, presently, and would-be religious should replace dangerous reliance upon belief with a fuller, more adequate expression of the challenge to an interrogating commitment to faith.

It is not the place here to weigh the possible relevance of the “neo-pragmatic” philosopher Richard Rorty’s work as a whole over his career. But it is useful to note and perhaps to find means of adapting a theme of his that would support a new hermeneutic that casts off “I believe” for a better concept and term. His consistent theme of the contingency in historical philosophical formulations speaks an historicist’s conviction that no vocabularies are inescapable in principle.[16] What he applies to philosophy I suggest we apply to historical religious vocabularies, wherever to the advantage of traditional religious vision struggling for expression through those vocabularies.

We should be ready, when prompted that is, to shift our vocabulary and to launch new, more serviceable terms. To observe that no vocabulary in historical philosophy is final, as does Rorty, is one thing. To apply this observation practically to the particular traditional use of “I believe” in the religious context is quite another. But to be pragmatic in the service of traditional religion, where vision and evolved circumstances would seem to call for the taking of such a risk, the re-wording of our faith commitment, should be considered.

The language of Scripture and of traditional formulations is, I propose, contingent in the sense Rorty ascribes to this term, despite its divine inspiration, as well as threatened by idolatry and its gaming by the demonic. The faithful do well to live carefully, of course, with this inevitable contingency. Here I propose only that “I believe” has become too much to ask, robbed as it is of its now elusive original meaning. It should be replaced, at the start, as individuals see fit, by a term or terms, by a language which more faithfully conveys the original scandal of the Gospel than does or can “I believe” today. I suggest: I “embrace” or “affirm” – or, to make a point, “I play.”

The example of poetic imagination producing poetic texts of faithful “play” can provide an inspiring example to those among the faithful perhaps reluctant to discard “I believe” as epistemologically inappropriate. Many, of course, will refuse to acknowledge that belief has been so thoroughly taken over by science. Many will not conclude that they can no longer personally make “I believe” mean for them what they wish it to mean.

But this is a losing battle. Our faith is increasingly losing its hold and it effectiveness. One great answer, as I have suggested above in comment on Auden, and in light of Derrida’s perhaps prophetic warning about language, is to find one’s own playfulness in reading, interpreting, and embracing Scripture for the sake of the infusing Word it contains despite the mischief of that containing. Of course, I mean by “play” not an instrument or agency of amusement but a serious dialectical juggling of language for its divine meaning, recognizing the threat of the structural demonic itself at play within the mischief of language that we would rather avoid or deny.

The verb “to game” is relevant here. The risk of playing and gaming as it implies losing as well as winning is to be embraced in the faith and trust, as Luther put it, that “one little word” shall defeat the demonic, that by the ultimately triumphant grace of God the demonic will be defeated by the divine.

Such a hermeneutic ploy proceeds admittedly from this writer’s going “to and fro in the earth” while carrying deeply planted personal faith. Hence the proposal is not at all exempt or immune from demonic threat. The reader will decide whether this proposal serves more the divine or more the demonic, and especially in light of the weight given above to the ever-so-worldly source, Derrida’s mischief-making differance. No one escapes the creative-destructive, divine-demonic dialectic. Nor should we allow ourselves to avoid considering it.

In the Protestant prophetic, if not in the Catholic sacramental strain of biblical Christianity, the gift of faith to the individual by the grace of God incorporates what I would call imaginative discernment as this plays in individual experience. We play our experience to find in it, as in biblical texts, the divine, the holy. There are no earthly rules for this play. It is for each individual, responding to Scripture, teaching, and varied experience, to play this possibility each in his or her own way.

Kevin Lewis is a professor of Religious Studies in the Department of Languages, Literatures, and Cultures at the University of South Carolina. Lewis graduated from the University of Chicago with a PhD in Religion and Literature in 1980 and published The Appeal of Muggletonianism in 1986. He has given papers on various dimensions of the Muggletonian tradition to the Carolinas Symposium on British Studies, the Southeastern section of American Academy of Religion, the Southeastern Nineteenth-Century Studies Association, and the local Columbia Metaphysicals.

[1] The Holy Bible, English Standard Version (Wheaton, IL.: Crossways Bibles, Division of Good News Publishers).

[2] Paul Tillich, The Interpretation of History, trs. N.A. Rasetzki and Elsa L. Talmey (Scribners, 1936).

[3] Paul Tillich, The Protestant Era (University of Chicago Press, 1948), xx, xxi.

[4] Ibid, xxi, ii.

[5] Paul Tillich, Systematic Theology, Vol. I University of Chicago Press, 1951), 114.

[6] Paul Tillich, “The Demonic,” tr. Garrett Paul, in Paul Tillich on Creativity (63-94), ed. Jacquelyn K. Kegley (Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1989), 63, 66, 68.

[7] Ibid, 69, 89, 70, 72.

[8] Ibid, 75.

[9] Timothy Beal, “The Bible is Dead; Long Live the Bible,” The Chronicle Review (April 17, 2011).

[10] Tillich, “The Demonic,” tr. Paul, 76, 82, 83, 87

[11] “The Devil, indeed, is the father of Poetry,” Auden observes in a Note to line 826 in Part II of “New Year Letter,” The Double Man (Random House, 1941), 116.

[12] W.H. Auden, “New Year Letter,” lines 826-33, 42

[13] Soren Kierkegaard, Fear and Trembling, tr. Alastair Hardy (Penguin Classic, 1985), 90.

[14] Cf. Brian Conniff’s entry, “Christianity,” in W. H. Auden Encyclopedia, ed. David Izzo (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co., 52-56).

[15] James P. Carse, The Religious Case Against Belief (New York, Penguin, 2008).

[16] Cf. especially Richard Rorty, Contingency, Irony and Solidarity (Cambridge University Press, 1989).