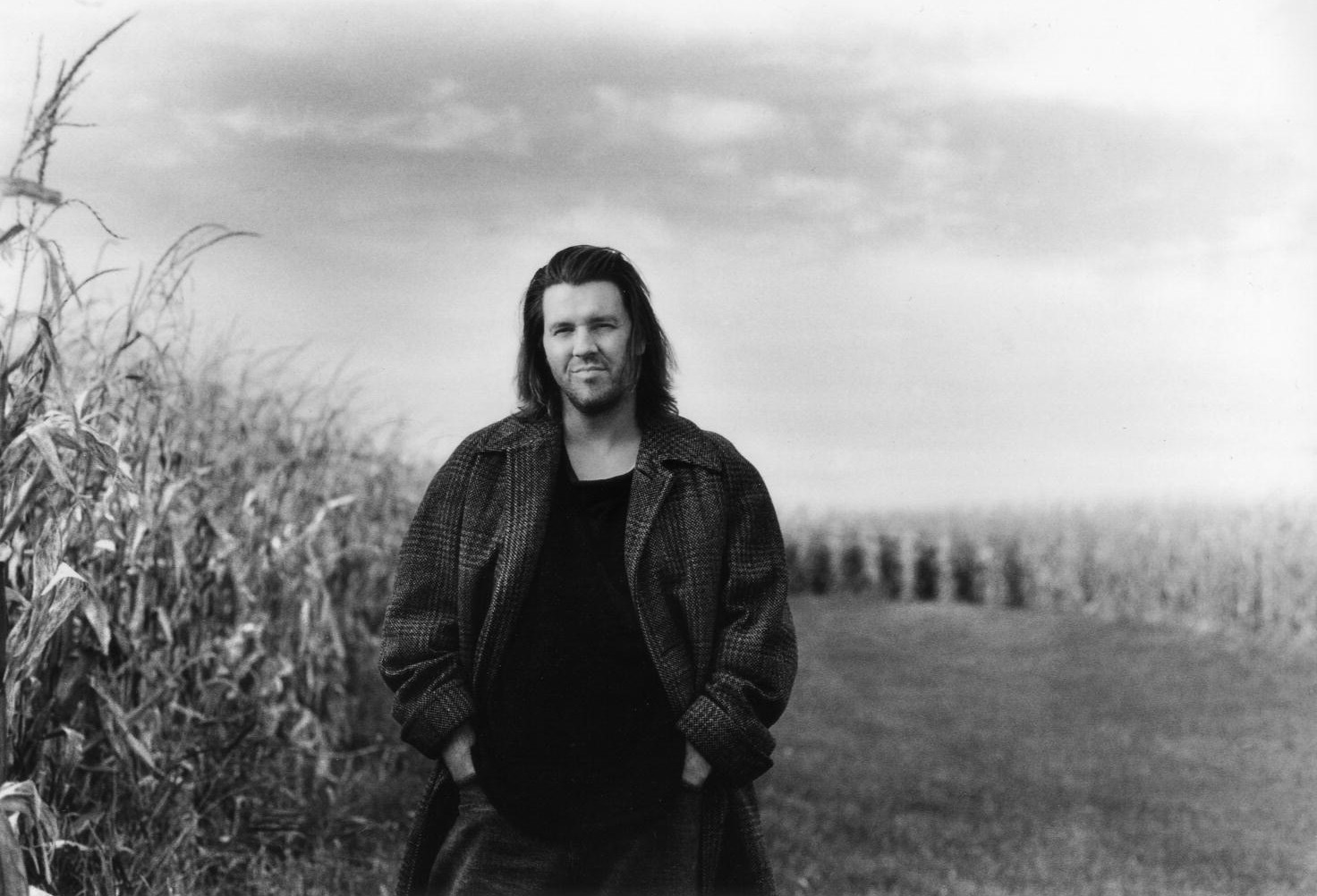

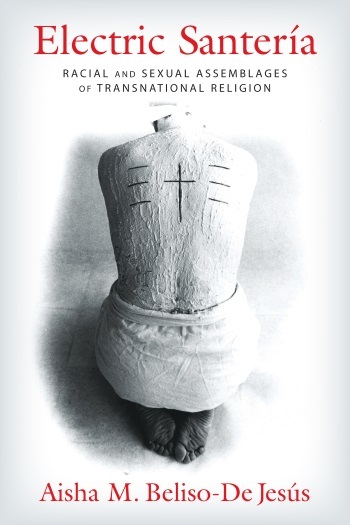

Miller, Adam S. The Gospel According to David Foster Wallace: Boredom and Addiction in an Age of Distraction. New York: Bloomsburg Academic, 2016. ISBN-10: 1474236979. Hardcover, paperback, e-book. 136 pages.

In this age of increasing literary interdisciplinarity, books such as Adam S. Miller’s latest project, The Gospel According to David Foster Wallace: Boredom and Addiction in an Age of Distraction, succeed or fail on their capacity to identify and illuminate compelling discursive intersections.

Miller’s is certainly a textbook case of such an enterprise: in his book, Miller, a professor of philosophy, sifts through Wallace’s enormous literary corpus in order to draw out key “religious themes” at play in the latter’s work. So for those keeping score at home, this is a book about religion, written by a philosopher, and whose source material is the literary canon of an American writer who had little to say about religion per se. But despite ample opportunities to lose his way through this Bermuda Triangle of academic thematics, Miller ultimately succeeds in weaving together this so-called “gospel” by emphasizing one point in which religious transcendence, embodied behavior, and phenomenology converge: immanence.

Should one skip the preface, however, one might miss the glue that holds the text together. Miller begins by reflecting on our unceasing, inescapable human impulse to worship. Human beings yearn for transcendence; some bring those concerns to mosques or monasteries while others worship at bars or baseball games.

Regardless of one’s religious convictions (or lack thereof), each one of us experiences the irreducibly human desire to escape, to transcend our circumstances. However, despite our best intentions, our yearn for transcendence will always invert into immanence, and our escapist longings will never break free of what Heidegger called our “en-worldedness”. And while some may consider this failure to transcend a bug in the system, Miller sees it as a pivotal feature to the character of worship. For this is worship’s revelation: religion is not meant to send us permanently past the stratosphere but to return us afresh to immanence.

As he writes, “The religious moment is not the moment when—whoosh!—the magic happens and the world seems full of a pantheon of idols able to satisfy. It’s the moment when—fshzzzt—the spell breaks, the credits roll, the lights come back up, and the world must be cared for again, as just whatever it is.”[1]

So what role does Wallace play in this “religious moment”, especially when on the face of things he wrote precious little about religion or worship? Those who have engaged Wallace’s work, if not especially his fiction, know that he was explicitly concerned with the quotidian minutiae of the human condition. We are, oddly, creatures with ethereal aspirations who often get stuck in the benign banalities of life: we get bored; we check our smartphones habitually; we work unsatisfying jobs because there are bills to pay; we change diapers.

As Wallace once said, these unremarkable conventionalities make it “distinctively hard to be a real human being.”[2] But this also helps explain why Wallace is so celebrated an author (and also why he is, at times, so excruciatingly difficult to read[3]). Wallace’s characters are often comically distracted and woefully preoccupied, stuck in their heads and hopelessly glued to self-perpetuating loops of addiction. However, they are still beings worthy of redemption nonetheless.

Thus what Miller does is illuminate the ways in which Wallace is concerned with critical living as a process of absolution: one must move from the escapist distractions of the mind to a bright-eyed encounter with the surrounding world. Miller’s Wallace, in other words, encourages us to move from our heads to our bodies, to attend to our worlds, to abide with intentionality, to “see the real at every turn”.[4]

It is in this emphasis upon the body that one picks up on strong overtones of  Miller’s material phenomenology, which seems to resonate deeply with the “new phenomenology” of thinkers such as Michel Henry. For Henry, affectivity is ultimately found in the radical immanent. Thus in a Henryite register, one might say that affectivity is the essence of life for Miller’s Wallace: human beings best experience the reality of their worlds through suffering, joy, laugher, despair, and boredom, all of which align when we “return to the present” by simultaneously “return(ing) to the body”.[5]

Miller’s material phenomenology, which seems to resonate deeply with the “new phenomenology” of thinkers such as Michel Henry. For Henry, affectivity is ultimately found in the radical immanent. Thus in a Henryite register, one might say that affectivity is the essence of life for Miller’s Wallace: human beings best experience the reality of their worlds through suffering, joy, laugher, despair, and boredom, all of which align when we “return to the present” by simultaneously “return(ing) to the body”.[5]

This materiality—this “religion of the physical”, as Miller puts it—exposes our desire for transcendence as a desire for disembodied-ness. We suffer from the same fate as Hal, the protagonist from Wallace’s Infinite Jest, or Toni Ware’s headless doll in Wallace’s The Pale King: our heads have come unthreaded from our bodies, which leaves us trapped in our own brains, distracted and unable to make ourselves heard.

Miller sees this shared, common condition of disembodied distraction as the closest Wallace comes to declaring a doctrine of original sin. Said differently, distraction from our bodies is a “weird kind of transcendence” that plays into our heads’ refusal to be local. Alternatively, Miller’s Wallace encourages us to disappear into that which confronts us: into silence, into boredom, into abiding, for it is through this sort of engagement into the surrounding world that our head can reconnect with our body and transcendence can invert into immanence. It is, as Miller puts it, a re-encounter and re-alignment between head and body: “Rather than leaving the world, the head, transcending itself, rejoins it.”[6]

In fact, it is this embodied saturation into that seems to mark the methodological fold between Miller’s new phenomenology and Wallace’s postmodern fiction. Thanks to thinkers such as Derrida, Blanchot, and Bataille, any soft distinction that once existed between literature and philosophy has now become contested. Something has become blurred between the literary conventions employed by fiction and the phenomenological experience of the reader as she reads.

In other words, we are captured by good stories precisely because narratives possess an uncanny ability to disrupt our subjectivity with some sort of constitutive excess. Good fiction is writing that extends an invitation to encounter that which is foreign to us. As such it ushers us into an experience of difference—a “conversion”, some might say—that erupts something within us with paradigmatic, transcendent-yet-immanent force. This is fiction’s transformative power and it is a power that was unleashed by Wallace.

Thus where one can find the same sort of immanent conclusions in Wallace’s nonfiction—essays such as “Derivative Sport in Tornado Alley”[7] or “Roger Federer as Religious Experience”[8], for example—it is in Wallace’s fiction that the reader can chance upon the sort of ‘god moments’ that turn us horizontally toward the plane of immanence instead of whisking us vertically into the heavens beyond. This possibility is good news; it is, if such a thing exists, the gospel according to David Foster Wallace.

____________________________________________________

[1] Adam S. Miller, The Gospel According to David Foster Wallace: Boredom and Addiction in an Age of Distraction, New Directions in Religion and Literature (London: Bloomsbury, 2016), xiii.

[2] See Stephen J. Burn, ed. Conversations with David Foster Wallace. (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2012), 26.

[3] Personally, I have attempted Wallace’s Infinite Jest three times. Each time, however, I throw the book across the room, usually somewhere around page 350.

[4] Miller, The Gospel, 87.

[5] Ibid., 95.

[6] Ibid., 67.

[7] See David Foster Wallace, A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again: Essays and Arguments (Boston: Back Bay Books, 1998), 3.

[8] See http://www.nytimes.com/2006/08/20/sports/playmagazine/20federer.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0