This article is the last of three installments. It was originally a paper given at the international conference “The Crisis of Representation” at Melk Conference Center (Stift Melk, Austria) sponsored by the Religion and Transformation in Contemporary Society Platform at the University of Vienna (June 27, 2017). The first installment can be found here, the second one here.

It is significant that Gramsci alluded in his notebooks to the emerging hegemonic role of journalism, which he characterized as a contingent of “pocket-geniuses”, which pretends to be “holding the whole of history in the palm of its hand.”[1]

But Gramsci was naturally unable to anticipate the digitization of both news and entertainment media where the “manufacture of consent” was boosted exponentially by an explosion, if not the amalgamation, of digital communication and commerce, especially what we now know as “social media” where Stiegler’s “tertiary retention” desiccates not only lived experience, but the spiritual fabric of human relationships, an electronic bellum omnium contra omnes that has become the strange and eminently hostile “twittering” virtual universe we know as politics in this day and age.

The demos that has been “undone” by this global apotheosis of grammatization and mediatization (by a proliferation of not only “fake news” but “fake agencies” of the electronic sort that cull, peddle, and feature what we are supposed to know through marketizing algorithms and hyperbots that exercise their own seamless, yet invisible control over the new “symbolic milieu” (Stiegler).

Stiegler himself calls for an insurrection against this pervasive alien dominion of a machinic “deep state” that might be fomented somehow through a recovery of the intimacy of wisdom itself, the wisdom of the body, of classical mnemosyne, of philosophy as the philia of sophia, something akin to Alain Badiou’s notion of love itself as a revolutionary praxis, or “truth procedure.” Such an insurrection requires the severance, according to Stiegler, of “the interface between the technical system and social systems” and the “economic system.”

The upshot would be what he calls l’économie de contribution (“the economy of contribution”), which he does not specify in any detail. Knowledge must come to be valued for its own sake, or at least for social flourishing. Such a society would be anti-consumerist. In an interview with a representative of the Macif Foundation, Stiegler comments:

This model [of the society of contribution] rests on investment and citizens taking responsibility. It differs from Fordism because it depends on de-prolaterisation (sic). For Marx, the workers are proletarized when their expertise is replaced by the machines that they serve. In the 20th century it was the consumers who were proletarized and we lost the old knowledge. Proleterization isn’t financial poverty, but the loss of knowledge. Consumers do not produce their own way of living, which is now prescribed by the big corporate names.[2]

Although Stiegler’s solution sounds vague and not a little utopian – and certainly does not have the “critical” transformational perspective we would expect perhaps from such incisive social and political theorizing – it steers us in a  direction from which the broader critique of neoliberalism often shies away. The crisis of neoliberal hegemony comes down to a crisis of liberal democracy stemming from the crisis of representation that can be tracked all the way back to the end of the Aufklärung.

direction from which the broader critique of neoliberalism often shies away. The crisis of neoliberal hegemony comes down to a crisis of liberal democracy stemming from the crisis of representation that can be tracked all the way back to the end of the Aufklärung.

It is a hollowing out of the political following upon the passage of dialectic into a highly undialectical planetary economism of algebrarically codified and commodified desire spurred on by the sophisms of marketing (in contradistinction to the production of exchange values on the market itself), where the sublimation of drives in the traditional Weberian analysis is transmuted into what Herbert Marcuse in his 1964 book One Dimensional Man called “repressive desublimation”, i.e., according to which “the progress of technological rationality is liquidating the oppositional and transcending elements in the ‘higher culture.’”[3]

Repressive desublimation, according to Marcuse, was a strategy of taking the rejected, or disowned, representations of instinctual life that could not be reconciled with the demands of the superego and making them the furniture of a new kind of “superegoic” system built around a performativity of guilty obsessions and pleasures, one which transmuted alterity into normativity.

The vamp, the national hero, the beatnik, the neurotic housewife, the gangster, the star, the charismatic tycoon perform a function very different from and even contrary to that of their cultural predecessors. They are no longer images of another way of life but rather freaks or types of the same life, serving as an affirmation rather than negation of the established order.[5]

Or another way of phrasing it would be to say that the new commerclal-saturated and techno-consumerist form of capitalism offered a mass-produced, commodified version of the alienated artist and intellectual, a pattern which was to become obvious after the Summer of Love in 1967 when the strange and hermetic “beatniks” of San Francisco suddenly morphed into the media icons that came to be known as the “hippies.” What David Brooks later would term the “bohemian bourgeoisie” (or “bobo”) was born.

So far as Marcuse was concerned, the commodified cultural “revolutionary” was the latest feint on the part of the surplus extracting machinery to neutralize all resistance to it. The bohemian bourgeoisie constitutes one more pinion in the transmission of

a rational universe which, by the mere weight and capabilities of its apparatus, blocks all escape. In its relation to the reality of daily life, the high culture of the past was many things— opposition and adornment, outcry and resignation. But it was also the appearance of the realm of freedom: the refusal to behave. Such refusal cannot be blocked without a compensation which seems more satisfying than the refusal. The conquest and unification of opposites, which finds its ideological glory in the transformation of higher into popular culture, takes place on a material ground of increased satisfaction. This is also the ground which allows a sweeping desublimation.[6]

Repressive desublimation greases the very skids of a smoothly operative biopower expressed through a virtually invisible regime that draws its legitimacy by allowing the pursuit of ever more rarified forms of “happiness,” including degrees of sexual libertinism that never would have been acknowledged, let alone countenanced, in earlier generations. After a while there is no limit that has not been transgressed, no standard that has not been been mocked, no measure of jouissance in the sense that Jacques Lacan meant it that has not become commonplace.

The syllogism-like exigency of the “categorical imperative” to shatter all moral and social inhibitions which the process of

cultural desublimation harnesses for the maintenance of consumer capitalism reached its apogee with the maturing of the counterculture in the last quarter of the previous century. The normalization of hedonism through the growth of a conventional, material culture that reflected the once, but no longer outré, lifestyles associated with an earlier underworld of “sex, drugs, and rock ‘n roll presented a challenge for late capitalism, whose own interior logic required an ongoing and ever more potent, if not addictive, commitment to the “creative destruction” of the existing order in a way that had never been imagined before.

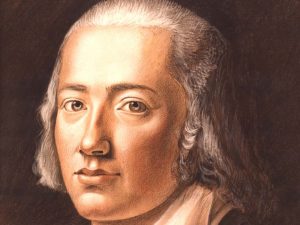

The fundamental challenge of the new era is to reverse this process of cultural desiccation and to recapture the sense of “real presence” in both our language in our social relations, and in our politics, and that will only be possible when, as the poet Hölderlin says,

Gardens stand together and already the glistening bud is beginning,

And the bird’s song invites the wanderer.

All seems familiar, even the hurried greetings

Seem those of friends, every face seems a kindred one.

Gärten stehen gesellt und die glänzende Knospe beginnt schon,

Und des Vogels Gesang ladet den Wanderer ein.

Alles scheinet vertraut, der vorübereilende Gruss auch

Scheint von Freunden, es scheint jegliche Miene verwandt. [4]

Carl Raschke is Professor of Religious Studies at the University of Denver, specializing in Continental philosophy, art theory, the philosophy of religion and the theory of religion. He is an internationally known writer and academic, who has authored numerous books and hundreds of articles on topics ranging from postmodernism to popular religion and culture to technology and society. Recent books besides Critical Theology include Force of God: Political Theology and the Crisis of Liberal Democracy (Columbia University Press, 2015) and The Revolution in Religious Theory: Toward a Semiotics of the Event (University of Virginia Press, 2012). His previous two books – GloboChrist (Baker Academic, 2008) and The Next Reformation (Baker Academic, 2004) – examine the most recent trends and in paths of transformations at an international level in contemporary Christianity. Faith and Reason: Three Views (IVP Academic, 2014), of which he is a co-author, is a conversation among three contemporary Christian philosophers. Finally, he is current managing editor of Political Theology Today and senior editor for The Journal for Cultural and Religious Theory.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] Antonio Gramsci, Selections From The Prison Notebooks (New York: International Publishers, 1992), Kindle edition, loc. 10500-10501).

[2] “Bernard Stiegler and the Economy of Contribution,” by Mariannetranslates, https://mariannetranslates.wordpress.com/2013/01/04/bernard-Stiegler-and-the-economy-of-contribution/. Translation from the French of interview, “Bernard Stiegler : ‘Les gens consomment plus parce qu’ils idéalisent de moins en moins’”, http://www.fondation-macif.org/bernard-stiegler-les-gens-consomment-plus-parce-quils-idealisent-de-moins-en-moins. Accessed June 20, 2017.

[3] Herbert Marcuse, One-Dimensional Man (London: Sphere Books, 1968), 75.

[4] Friedrich Hölderlin, “Homecoming/To Kindred Ones”, in Martin Heidegger, Elucidations of Hölderlin’s Poetry, trans. Keith Hoeller (New York: Prometheus Books, 2000), 27.

[5] Herbert Marcuse, One Dimensional Man (New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1964), 62.

[6] Ibid., 75.