Mack, Mehammed Amadeus. Sexagon: Muslims, France, and the Sexualization of National Culture. New York City NY: Fordham University Press, 2017. ISBN-10: 0823274616. Hardcover, Paperback, E-book.

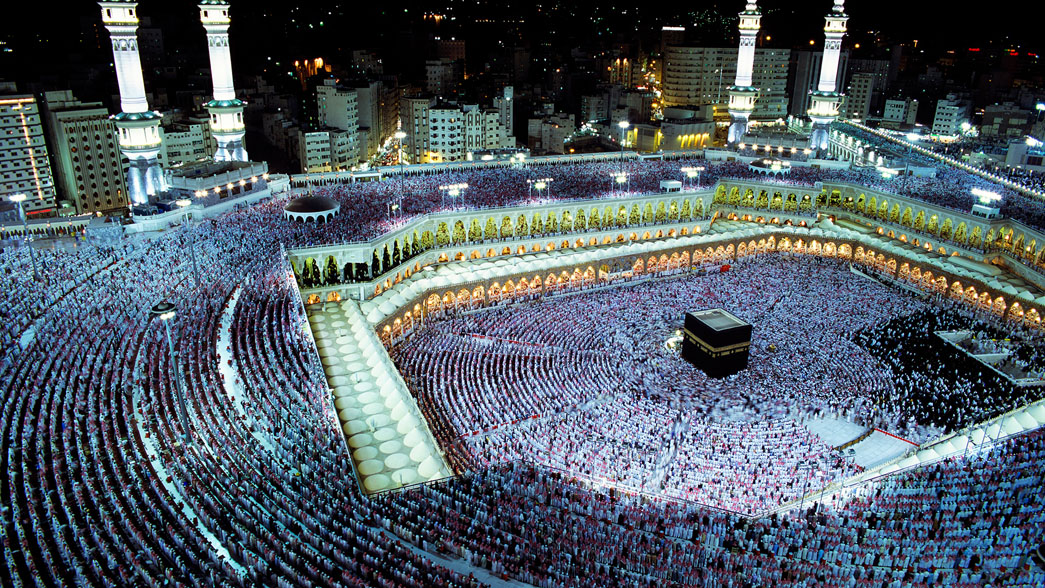

The title of Mehammed Amadeus Mack’s latest book Sexagon: Muslims, France, and the Sexualization of National Culture is a wordplay within a wordplay, referencing French slang for the country itself, ‘the hexagon’. This wordplay, and negotiation of identity of the French culture at large, is brought up repeatedly within the work. Mack focuses primarily on the perception of Muslims (specifically Arab and African Muslims) in contemporary French society and media.

Mack’s central argument lies within the paradox and negotiation that settles easily within the French world, where Muslims are simultaneously too sexual, and thus risking the safety of a fragile French society, as well as not sexual in the right ways, holding onto conservative and decidedly ‘non-French’ values and customs from their heritage nations. The book expands from this central premise, drawing on a host of disciplines and theories to better illuminate the media landscape in relation to the Muslim person.

Mack’s early chapters focus first on the idea of gender within French society. Chapter One particularly focuses on the banlieue, or what would be more understood in English as ‘the projects’ or government-provided housing. The banlieue is usually a space on the outskirts of major French cities, where low-income and immigrant citizens exist. Mack showcases the negotiation of social and conceptual identity for these two distinct spaces. The banlieue is seen as not innately a French space, possessed more by the Franco-Arab Muslims than by ‘true’ French citizens. Therefore, it is a masculine space, controlled by the roaming gangs of virile Muslim men (and occasionally women). Meanwhile, the traditional image of France and of French cities are feminine with most media landscapes portraying France as ‘the motherland’ and somehow an innately feminine space, ripe for defilement and subjugation by those that are somehow not French enough.

Chapter 2 is the complement to this exposure of conceptual gender and space, breaking down the immigrant family unit and exposing the stereotypes inherent within French media landscapes. The seemingly ever-present stereotypes of immigrant families is well in present in France, according to Mack. The fathers are absent, both physically and emotionally, meanwhile the mothers worship their sons and ignore their daughters, smothering yet controlling. These form the basis for Mack’s three great images: the violent adolescent, the veiled woman/girl, and the impotent man. This forms as the framework for the rest of the book, as examples and case studies of popular and well-regarded media productions that engage with these three archetypes.

Mack’s violent adolescent is the young Arab, African, or Muslim man. He dresses in baggy clothes, and is presented like a thug. The juvenile doesn’t travel alone, but in groups. They are antagonistic towards effeminacy whether it’s projected in man or woman, and are always willing to act on it to showcase their virility.

The veiled woman, in contrast, is demur and unassuming. She is too in control of her own sexuality and gender presentation,  hobbled by the cultural stigma that prevents her from being a “real” French woman. She also is then seen as the honeypot, capable of seducing French morals and values away from the population.

hobbled by the cultural stigma that prevents her from being a “real” French woman. She also is then seen as the honeypot, capable of seducing French morals and values away from the population.

Finally, the impotent father is the result of growing up as an immigrant. The impotent father is unable to control his family in this new world, unwilling to engage in the sexual conversation of the culture, and is emasculated by his position in the French nation. These archetypes are stereotypes, and as Mack asserts, entirely incorrect, but are helpful for French media to categorize and police identities outside the constructed mainstream. These archetypes allow the French to judge and criticize complex issues such as immigrant sexuality, cultural attachment, and familial structure.

What strikes in these early chapters are the attention and detail Mack pays to the complex media narrative around Arabs, Africans, and the general Muslim population in France. Rather than seeking out specific percentages or grouping media narratives into specific groups, he focuses rather on the tropes that he sees as problematic and endemic within the production of French media. Importantly on a qualitative work of this level, Mack does not spend time trying to moralize or even judge the media tropes in French culture. To Mack, the problem is that the stereotypes portrayed are reductive and create unproductive dialogue amongst Franco-Muslims and non-Muslim French.

There are many French Muslims that are indeed socially conservative, they may veil, and often have a very different idea of sexuality and the public-private divide compared to many non-religious and Christian French citizens. This, essentially, is why Mack creates the archetypes he does for his future analysis. His three provided archetypes are the most common, and focus specifically on the Franco-Muslim relationship to sex and the public-private divide. Furthermore, it grants Mack the flexibility to simultaneously expand the reductive narratives while also allowing him to reveal the problems of simply switching the trope.

Mack sees these tropes in a similar light to how feminist literature speaks of the Madonna-Whore trope, where women are either bastions of virtue or seductive beings of man’s downfall. Mack wants to avoid a similar problem with his given trope-narratives and wants to create nuance, avoiding general claims about the lives of Franco-Muslims and instead complicate the simple ideas of cultural binaries for marginalized communities shown in media.

The last chapters of the book examine complex media studies for the various Muslim peoples that exist within France. Mack spends most of his time breaking down how popular media forms (TV, film, selective novels) either engage with or subvert the traditional tropes and stereotypes of Muslim-French men. For these men specifically, Mack draws heavily on post-colonial theory, queer theory, and media studies in order to better understand why these media forms engage as they do. Mack’s most compelling case study is about Franco-Arab actors within the French cinema.

Many of the more well-known actors in this vein earn their careers by starring within arthouse cinema productions, and almost always are cast as an ethnic man with an ambiguous or separated sexuality. This role has become a trope within French cinema, known both as the homo de service (token gay) and the arab de service (token Arab). Service also has multiple meanings within French language, and these characters are also seen mostly as plot-points or “servants to the story.” They often times are there to fulfill the French idea of the hyper-virile, masculine Muslim man to expose the protagonist (usually male) to an exotic and complex view of sexuality, straight in daylight and gay in moonlight. These protagonists are also almost always hurt by their sexual partner, being left with broken hearts or bruised bodies when attempting to drag the other man into the light and “proper” French society.

Many of the more well-known actors in this vein earn their careers by starring within arthouse cinema productions, and almost always are cast as an ethnic man with an ambiguous or separated sexuality. This role has become a trope within French cinema, known both as the homo de service (token gay) and the arab de service (token Arab). Service also has multiple meanings within French language, and these characters are also seen mostly as plot-points or “servants to the story.” They often times are there to fulfill the French idea of the hyper-virile, masculine Muslim man to expose the protagonist (usually male) to an exotic and complex view of sexuality, straight in daylight and gay in moonlight. These protagonists are also almost always hurt by their sexual partner, being left with broken hearts or bruised bodies when attempting to drag the other man into the light and “proper” French society.

While this unpacking of stereotypes is one major strand within the book, the other strand that Mack accomplishes is a nuanced study of the reality of Franco-Muslim men and women within France, an area where most authors do not succeed. Instead of simply a media study or media review, Mack invests time and effort to weave these two competing strands against their will, forcing two various different narratives to be in contact and conversation.

Every stereotype or trope within French media is forced to encounter the lived reality of people in the banlieue, an encounter that is stressful on both narratives as it reveals the positive and negative of each narrative. Mack does not shy away from the semi-closeted existence of queer Franco-Muslims yet does not shy away from the often impoverished and oppressed reality of these same peoples in return. Instead, Sexagon reveals the required interaction of these two narratives and how often times, one cannot exist without the other.

Many newer films in France subvert the trope of the homophobic Arab man or the submissive Arab woman, allowing for greater visibility to the competing narratives within the nation. Pop psychology of the immigrant condition has been pushed aside in favor of a more practical attempt at true post-colonial work in order to recognize and assimilate Franco-Muslims better and more efficiently. Mack addresses the problematic nature of these growths, which still push Muslims as an ethnic and sexual Other that can never be seen as truly and inherently French. This is specifically why Mack does not seek to defend or attack the lives of Franco-Muslim individuals and focuses on the media narratives. Mack would be the first to acknowledge that many Franco-Muslims suffer from internalized homophobia or limiting and overbearing families. He, however, also wants these lives and experienced to be better explored and understood in modern French media, without forcing the trope to simply be a subversion which rejects the character and their cultural heritage.

Sexagon is an ambitious work, seeking to understand a qualitative perspective that is tenuous at best to present. Despite this, Mehammed Amadeus Mack largely succeeds in his attempts to showcase both the popular narrative and the lived experiences and identities of French Muslims, no matter how contrary they often seem when lain next to one another. Even more so, Mack manages to walk a fine line of accurately revealing and discussing controversial issues such as homophobia, racism, and sexism in French society without placing the blame on any one group of individuals or social group. His focus on the media productions itself are what sets his book apart from others, as it reveals the inner biases we all possess in society, both Muslim and non-Muslim, and how it can affect cultural production and cultural mindsets as a result. While the work sometimes delves too far into the portrayal of specific films or roles as a spokesman for the entire media landscape, all-in-all Sexagon is a key intellectual exercise in how to understand Islam, Muslims, and its place within the French imagination as well as the growing ethnic coalition that is the French people.

Trevor Wolff is a graduate student at the University of Denver. His academic foci are Modern Islam, post-colonial negotiations of religion, and queer identity navigation in faith.