The following is the second part in a two-part installment. You can find the first part here.

Maintaining a State of Hope and Taking a Transcendent Perspective about Human Worries

One indicator of mental health is the ability to maintain a state of hope in the face of life’s struggles. Some researchers have concluded that humans have a natural propensity for religious experiences, which means that persons tend to be more anxious and worried when they lack a religious orientation.[1] In one of His teachings, Jesus offered helpful thoughts in the following quotations. He encouraged people to travel light emotionally and to take a transcendent perspective toward common human worries.

Therefore I tell you, do not worry about your life, what you will eat or drink, or about your body, what you will wear. Is not life more than food and the body more than clothing? Look at the birds in the sky, they do not sow or reap, they gather nothing into barns, yet your heavenly father feeds them (Matt. 6:25-26).

So do not worry about tomorrow; for tomorrow will bring worries of its own. Today’s trouble is enough for today (Matt. 6:34).

The advice given in this teaching about the value of depending on a higher power and about taking one day at a time is viewed as life-saving by members of Alcoholic Anonymous and other 12 step self-help.[2] No therapeutic techniques suggest that one should endlessly pursue perfection, or insist on doing things the right way, consistently. In fact, all therapeutic models suggest that accepting what one cannot change is healthy.[3] The serenity pray – “God grant me the serenity to accept things I cannot chance, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference” – is based in the belief that one should depend on faith in God for those things that cannot be changed.[4]

Many researchers have found that well-being is a consequence of not worrying over what one cannot control.[5] Rosmarin is a part of a group of researchers at Mclean Hospital, an affiliate of Howard University; based on their research, they concluded that persons who believe in a benevolent God worry less about life’s daily problems and concerns. In addition, they call greater clinical focus on religion in improving therapy outcomes.

The outcome of believing in Jesus’ teachings may be that one is less burdened by common problems and overall has lower anxiety and reactivity to negative events. In terms of Bowen’s System’s Theory, not being negatively affected by events is associated with increased differentiation and emotional health.[6] The implied message in Jesus’ teachings is toward greater differentiation and less emotional reaction. By accepting things that cannot change, a family is less likely to project negatively onto a child or develop complementary relationship in which one member is adaptive and the other dominant.

Second-Order Thinking

Strategic therapists have delineated two approaches to problem-solving: first-order solutions and second-order solutions.[7] First-order solutions involve strategies in which the problem solver applies more of the same kind of thinking until the problem is ameliorated (e.g. if one is cold, he or she continues adding layers of clothing until warm). First-order solutions appear to be “logical” and are most often used in daily problem-solving. Second-order solutions involve strategies, which often appear “illogical” at first viewing since they do not entail more of the same approaches to problem resolution. A second-order approach involves conceptualizing the parameters of the problem beyond the original “nine dots.”

Jesus appears to advocate second-order thinking in many of his teachings since his solutions seem “irrational” on first viewing. When Jesus began a teaching with “You have heard it said…” it denoted that a paradox would follow. Note the advice Jesus gives in the following teachings:

You have heard it was said, ‘An eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth.’ But I say to you, do not resist an evil doer. But if anyone strikes you on the right cheek, turn the other also; and if anyone wants to sue you and take your coat, give him your cloak as well, and if anyone forces you to go one mile, go also the second mile. Give to everyone who begs from you, and do not refuse anyone who wants to borrow from you (Matt. 5:38-42).

But I say to you, love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you (Matt. 5:44).

What second-order thinking does is it allows a person to step outside the expected boundary of a problem and view both the problem and the solution from another perspective. What is implied in Jesus’ use of second-order thinking is the effect that second-order processes have on others. For example, when Jesus says to resist evil, he is speaking more from a systemic perspective than an individual perspective.

One can affect others by acting in ways that are unexpected or out of the ordinary. Second-order thinking drastically increases one’s repertoire of behaviors and ability to affect others in indirect ways. Second-order thinking reduces the tendency to pursue goals in a linear manner. Instead of setting success as the goal, one should immerse oneself in things that are greater than the self.[8] As one forgets about pursuing goals, one is more likely to be successful in achieving them.

The marriage and family therapy literature is replete with the use of second-order thinking, including paradox.[9] A simple therapeutic technique is for the therapist to say something that appears false, but holds a profound truth that may not be consciously acknowledged. Second-order thinking increases thinking outside the box and introduces opportunities for both seeing the problem in a new light and for developing creative responses. Jesus used this type of paradox in the following verses:

Whoever tries to save his life will lose it; whoever loses his life will save it (Luke 17:33).

For everyone who makes himself great will be humbled, and whoever humbles himself will be made great (Luke 14:11).

It is much harder for a rich man to enter the Kingdom of God, than for a camel to go through the eye of a needle (Luke 18:25).

Social Interest

One tenet of Adlerian Psychology is that the measure of one’s mental health is indicated by his or her level of social interest, i.e., the degree to which the individual contributes to the welfare of fellow humans.[10] According to Ferber et al., Adler believed that humans, from birth, are socially embedded and the psychological health of each person is enhanced when he or she fulfills his or her intimacy needs by making socially useful contributions to the welfare of the group. The view that our relationships are key to healthy mental and physical states was recently collaborated by the findings of an 80-year-old longitudinal research project.

This study has been referred to the “Harvard Study of Adult Development” which began in 1938.[11] Only 19 of the original study subjects of 268 are still alive. The study found that intimate relationships and how happy persons are in their relationships is related to their mental and physical health. While these findings were somewhat surprising to the researchers, they do clearly illustrate the proposition that “My happiness is bound up with your happiness.”

Unfortunately, in the present state of human evolution, most people do not intuitively realize that their happiness and psychological well-being is dependent on love for one another. Since this knowledge is not self-evident, it must be imparted by an external social voice such as the institution of organized religion. Christian religions, by reminding their adherents of Jesus’ teachings that “you shall love your neighbor as yourself,” continually enhance the level of social interest among humans, thereby increasing the level of psychological health in individuals and families. To the rich young ruler who asked Jesus about discipleship, Jesus responded:

‘…Go and sell your possession, and give the money to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven: then come and follow me.’ When the young man heard this word, he went away grieving, for he had many possessions (Matt. 19:21-22).

Social integration was a focal point in Durkheim’s theory.[12] According to Idler and Kasl, the social function of religion promotes intimacy and belonging with others.[13] Enhancing one’s commitment to others promotes a stronger link between the individual and social institutions. All models of psychotherapy endorse adequate social involvement rather than isolated and individualistic pursuits.

Requirement of Third-Order Change

Third-order change is rarely talked about in the family literature. Nevertheless, it could very well be that families must make a radical change occasionally in order to adapt or continue functioning. While a second-order change is a change in the system itself, a third-order change is a radical discontinuous change in which new beliefs and behaviors replace old ways of thinking and behaving.[14] A religious conversion experience is one way to conceive of third-order change. In order to make a third-order change, one must be aware that a fundamental change is needed to go forward. The present framework or paradigm that underlies a person’s decision-making process, must be challenged by new and creative thinking. The third-order change redefines the identity so that one is fundamentally different from before. Jesus required third-order change when he called his followers.

A scribe then approached and said, ‘Teacher, I will follow you wherever you go.’ And Jesus said to him, ‘Foxes have holes, and the birds of the air have nests; but the son of man has nowhere to lay his head.’ Another of his disciples said to him, ‘Lord, first let me go and bury my father.’ But Jesus said unto him, “Follow me: and leave the dead to bury their own’ (Matt. 8:19-22).

Some, however, did receive him and believed in him; so he gave them the right to become God’s children (John 1:12).

While little is written about third-order change in the family literature, there are situations in which this kind of change is necessary for optimal functioning. For example, for a woman in an abusive relationship who does not believe in divorce, a third-order change may be necessary to terminate the relationship. She may have to change her views about commitment to marriage and family in order to escape the abuse.

Being able to change one’s identity or view of reality under severe circumstances creates greater likelihood that one can adjust. It could be argued that much of therapy is third-order change because a new direction in a person’s life may occur only from changing his or her internal paradigms that filter out new or unfamiliar experiences. Systemic therapists focus on change techniques that lead to different outcomes.[15] For example, reframing, or the redefining of a behavior, symptom, or belief is a technique that systemic therapists use that changes one’s perspective and, therefore, creates a fundamental change in the way one behaves.

The Blissful Aspect of Altruistic Sacrifice

Sacrifice is the forfeiture of something highly valued for the sake of something that has a greater value. According to this definition, sacrifices have both a negative and a positive aspect. Joseph Campbell noted that the blissful aspect of sacrifice, depicted in various religious rituals, is often overlooked by persons who tend to see only the onerous and negating dimension of sacrifice.[16] While the Jewish tradition was steeped in the command to love God and one’s neighbor, Jesus added another dimension when he joined the two into one commandment. The following sayings of Jesus emphasize the positive consequences that flow from self-achieved submission:

‘For those who want to save their life will lose it, and those who lose their life for my sake will find it’ (Matt. 16:25).

‘Very truly I tell to you, unless a grain of wheat falls into the earth and dies, it remains just a single grain; but if it dies it produces much fruit’ (John 12:24).

Living with a partner in a committed relationship, caring for children, taking care of elderly family members, indeed, all manifestations of mature love involve some degree of altruism, or unselfish behaviors that foster the welfare of others. Researchers have found that sacrifice is important in intimate relationships.[17] Sacrifice is more likely to occur when there is high commitment to each other, a high level of trust and the belief that the partner will reciprocate.

The compromises required in living a responsible adult life may seem emotionally unbearable unless there is a counterbalancing sense of personal fulfillment that flows from acts of selflessness. New research indicates that sacrifice for the partner is rewarding to both partners when it is acknowledged and then reciprocated.[18] The above-mentioned sayings of Jesus encourage us by reminding us of the fruitful and enduring consequences of sacrificial deeds.

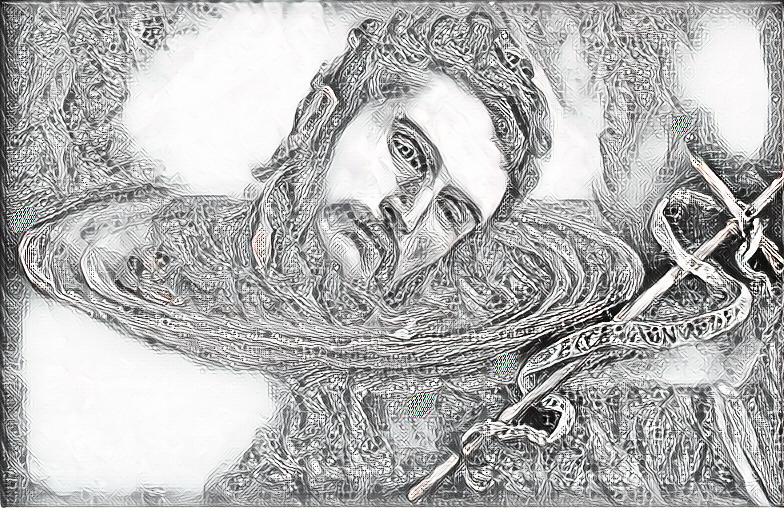

The Courage to Live

As Jesus went to Jerusalem for the last time, it is clear that he anticipated his betrayal and death. The courage to encounter these events despite the inevitable outcome echoes the writings of philosophers, such as Tillich and Heidegger, who believed that overcoming the dread of death is the essence of living.[19] While to some, death signals an end to life and the accomplishments that mark individuals, according to San Filippo, Heidegger believed that status and accomplishments in life carry no weight for the afterlife.[20] The recognition that humans will pass away and coming to terms with the world continuing after one has died is the ticket to authentic living in the present. One can only fully participate in living when the acceptance of one’s own death has been fully faced.

From that time on Jesus began to show to his disciples that he must go to Jerusalem, and undergo great suffering at the hands of the elders and chief priests and scribes and be killed, and the third day be raised. And Peter took him aside and began to rebuke him, saying, ‘God forbid it Lord! This must never happen to you.’ But he turned and said to Peter, ‘Get behind me Satan: you are a stumbling block to me: for you are setting your mind not on divine things but on human things’ (Matt. 16:21-23).

The fear of death is related to emotional and psychological disorders.[21] All Christians believe that death is not the end of life and that there is an afterlife.[22] This belief makes the acceptance of death less disturbing and fearful.

I am the resurrection and the life, whoever believes in me will live, though he dies; and whoever lives and believes in me will never die (John 11:25-26).

The acceptance of death also reduces the effect of the importance of accumulating material possessions in this life, while deepening one’s sense of security. Consequently, emotional issues regarding death are less prevalent with Christians.

And he went on to say to them: Watch out, and guard yourselves from all kinds of greed; for a man’s true life is not made up of things he owns, no matter how rich he is (Luke 12:15).

It is consistent with all therapeutic models that the acceptance of death frees one to live authentically in the present.[23] As one is freed from the fear of death to live in the present, one can find meaning in life regardless of the circumstances.[24] There is research evidence that religious faith not only provides meaning and the ability to accept losses, but also enhances a person’s capacity to face death.[25]

Conclusion

This article is an attempt to understand the therapeutic value of the underlying messages in the teachings of Jesus. The authors conclude that His teachings utilized many applied therapeutic ideas, such as second-and third-order thinking, reframing, acceptance of death, acceptance of circumstances, altruism, and maintaining hope. Many of these ideas were only recently incorporated into therapeutic models with the rise of systemic thinking.

Furthermore, it is our belief that these themes are related inherently to the mental and physical health advantage of believers through providing cognitive and emotional constructs that allow for adaptations to crises and novel and unique responses to life’s events. While this analysis was limited to the teachings of Jesus Christ, it would be expected that all religious and spiritual experiences would provide advantages in cognitive and psychological adjustments in contrast to secular or non-religious thinking. We hope that future researchers will address these cognitive and emotional themes in empirical research.

Thomas W. Roberts is a Professor Emeritus and former Chair of the Department of Child and Family Development, San Diego State University.

Delbert J. Hayden is a Professor Emeritus in the Department of Counselor Education at Western Kentucky University.

[1] M.A. Ferguson, J.A. Nelson, J.B. King, L. Dai, D.M. Giangrasso, R. Holman, J.R. Korenberg, and J.S. Anderson, “Reward, Salience, and Attentional Networks are Activated by Religious Experiences in Devout Mormons,” Social Neuroscience 13, 1 (2018): 104-116. doi:10.1080/17470919.2016.1257437; B. Johnson, G. Holiday, and D. Cohen, “Heightened Religiosity and Epilepsy: Evidence for Religious-Specific Neuropsychology,” Mental Health and Culture 19, 7 (2016): 704. doi:10.1080/136761238449.

[2] A. Mendola and R.L. Gibson, “Addiction, 12-Step Programs, and Evidentiary Standards for Ethically and Clinically Sound Treatment Recommendations: What should Clinicians do?” American Medical Association Journal of Ethics 18, 6 (2016): 646-655.

[3] S.C. Hayes, K.D. Strosahl, and K.G. Wilson, Acceptance and Commitment in Therapy: The Process and Practice of Mindful Therapy, 2nd ed, (New York: Guilford, 2012).

[4] H.G. Koenig, L.K. George, and I.C. Siegler, “The Use of Religion and Other Related Emotional-Regulating Coping Strategies Among Older Adults,” The Gerontologist 28, (1988): 303-310.

[5] M.K. Holt and M. Dellmann-Jenkins, “Research and Implications for Practice: Religion, Well-being/Morale, and Coping Behavior in Later Life,” Journal of Applied Gerontology 11, (1992): 101-110; Moberg, 1970; Rosmarin, 2018).

[6] M. Bowen, Family therapy in clinical practice, (New York: Jason Aronson, 1978).

[7] Haley, Problem-Solving Therapy.

[8] D. B. Feldman, “The paradoxical secret to finding meaning in life,” Psychology Today, 2018.

[9] A. Bjornestad and G.A. Mims, Paradoxes and Paradoxical Interventions, (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2017).

[10] A. Ferber, M. Mendelsohn, and A. Napier, The book of family therapy, (New York: Science House, 1973).

[11] L. Mineo, “Good Genes are Nice, but Joy is Better,” The Harvard Gazette, April 11, 2017.

[12] E. Durkheim, The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life (tr. by J. W. Swain), (New York: Free Press, 1965).

[13] Idler and Kasl, “Religion, disability, depression, and the timing of death.”

[14] J.M. Bartunek and M.K. Moch, “First-Order, Second-Order, and Third-Order Change and Organization Development Interventions: A Cognitive Approach,” Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 23, 4 (1987): 483-500.

[15] Rudi Dallos and Ros Draper, Introduction to Family Therapy: Systemic Theory and Practice, 3rd edition, (Berkshire, UK: McGraw-Hill, 2015).

[16] Joseph Campbell, Myths to Live By, (New York: Viking Penguin, 1993).

[17] A. Kogan, E.A. Impett, C. Oveis, B. Hull, A.M. Gordon, and D. Keltner, “When Giving Feels Good: The Intrinsic Benefits of Sacrifice in Romantic Relationships for the Community Motivated,” Psychological Science 21, 12 (2010): 1918-1924.

[18] Mariko L. Visserman, Emily A. Impett, Francesca Righetti, Amy Muise, Dacher Keltner, and Paul A.M. Van Lange, “To ‘see’ is to feel grateful? A quasi-signal detection analysis of romantic partners’ sacrifices,” Social Psychological and Personality Science, 2018, DOI: 10.1177/1948550618757599.

[19] P. Tillich, The Courage to Be, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1952).; M. Heidegger, Existence and Being, (Chicago: Gateway, 1968).

[20] D. San Filippo, “Philosophical, Psychological and Spiritual Perspectives on Death and Dying,” Faculty Publications 31, (2006).

[21] L. Iverach, R.G. Menzies, and R.E. Menzies, “Death Anxiety and Its Role in Psychopathology: Reviewing the Status of a Transdiagnostic Construct,” Clinical Psychology Review 34, 7 (2014): 580-593.

[22] San Filippo, “Philosophical, Psychological and Spiritual Perspectives on Death and Dying.”

[23] Iverach, Menzies, and Menzies, “Death Anxiety and Its Role in Psychopathology.”

[24] V. Frankl, Man’s Search for Meaning, (Boston, MA: Beacon, 1963).

[25] H.G. Cox and A. Hammonds, “Religiosity, Aging, and Life Satisfaction,” Journal of Religion and aging 5, (1988): 1-21.