The following is the sixth lecture in an eight-lecture series. The most recent one can be found here.

I started the last couple of lectures with elaborate explanations of the meaning and the relevance of the topic. This seems less necessary today. That theology as the task of thinking and speaking about God is closely connected with our understanding of language, its character, and its limitations seems as obvious as it has been traditional.

Christian theologians have always understood that their attempts to articulate insights relating to the being of God risk missing their topic simply due to their need to use language that is primarily geared for an orientation within the world of our everyday experience and will thus inevitably create complications if applied to a reality that is supposed to be utterly different from that world.

The church fathers were quite aware of the fact that talking about the intra-trinitarian relationship between the Father and the Son they could not fail to evoke unsuitable associations whatever biblical or philosophical terminology they employed for it. And during the scholastic period, theories about analogical or univocal application of predicates to God were equally fueled by the awareness of a linguistic barrier to any theology proper.

If we then look at the influence of modern views on language on 20th century thinking about God, we must not make the mistake of assuming that theology was, all of a sudden, confronted with a problem it had never been aware of before. The opposite is the case; and one might even surmise that historically, a number of the more recent philosophical or linguistic theories owe some debt precisely to theological musings developed to investigate how language could ever adequately express truth about the supernatural.

Yet this is not to say that theological thinking about God has not been influenced in its turn by non-theological debates about language. This would seem all the more unlikely given the enormous prevalence of these debates throughout the 20th century. There was a point, towards the end of that century, when it appeared as if language would ultimately emerge as the one major philosophical concern of the century. I don’t know whether this is the result historians of philosophy will arrive at 100 years from now, but there can be but little doubt that language has been a dominant theme in (very broadly) philosophical scholarship during that time.

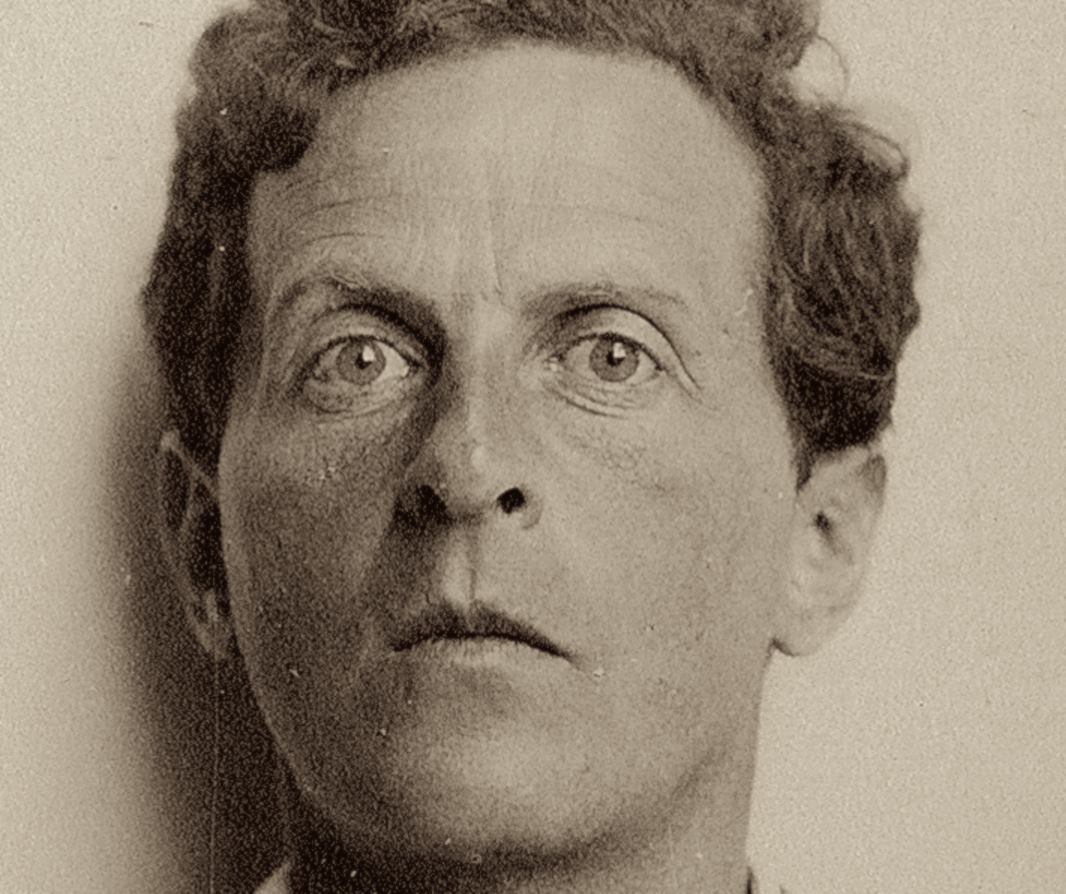

What has made it so pervasive is not least that two very different philosophical traditions seemed to converge on the importance of an understanding of language for any philosophical thought. There is on the one hand, and this may be what most of you are familiar with in the first instance, the tradition of analytic philosophy, which in many ways goes back to the groundbreaking work of Ludwig Wittgenstein.

Wittgenstein’s contribution to our understanding of language is complex even if we confine ourselves here to its consequences for theology. At the very least we have to look separately at the two versions of his own philosophy, which Wittgenstein has produced. These are mainly contained on the one hand in his early Tractatus logico-philosophicus, in his posthumously edited Philosophical Investigations on the other.

It is useful to note beforehand that both these philosophies share one major motive, and this is hostility towards traditional metaphysics. Wittgenstein believed throughout his career that many traditional philosophical problems were in fact pseudo-problems, which could be exposed and disposed of by linguistic analysis. There can be no doubt that much of traditional theology falls in the category of such pseudo-problem, and thus, whatever gain theology may make from considering Wittgenstein’s philosophy, it must not be ignored that the structure is once again that of a challenge to traditionally accepted ways of talking about God to which theology needs to respond.

Both the analysis of the problem and the remedy offered against it, differs between the early and the late Wittgenstein. The Tractatus, which shows Wittgenstein as part of the logical positivism of the so-called Vienna Circle, is predicated on the assumption that philosophy has the task of sanitising language. Language can only express a very limited number of statements about the world, essentially those that can empirically be verified. It is therefore necessary for philosophy to develop an artificial language that avoids all the pitfalls ordinary language leads us into due to its use of idiomatic and metaphorical expressions.

Does this leave any room for theology? In one sense it doesn’t, and most philosophers belonging to the Vienna Circle saw critique of religious belief as one of their foremost tasks. Wittgenstein’s position, however, is slightly more complicated. For in a famous statement towards the end of the Tractatus, Wittgenstein introduces the concept of the mystical:

6.522 There are, indeed, things that cannot be put into words. They make themselves manifest. They are what is mystical.

In other words, while Wittgenstein clearly is adamant in the Tractatus to argue for an understanding of language that excludes the expression of anything beyond the empirical realm, he is quite conscious of the fact that such a move disqualifies the philosopher from an actual critique of religion insofar as the possibility of the reality claimed within religion simply is beyond the limits of the language he has adopted.

This is in fact very much like the consequence of Kant’s position in the Critique of Pure Reason. Yet Wittgenstein goes to some extent beyond a position of mere agnosticism in regard to non-empirical reality. In the passage I quoted, he seems willing to accept that there may be reasons for making the acceptance of such reality plausible albeit not speakable. ‘They manifest themselves.’ Once again, we may find ourselves reminded of Kant’s reintroduction of theism via practical reason – Wittgenstein’s position certainly seems to suggest a kind of experience that could be claimed for religion (if we are allowed to substitute this term for his ‘mystical’).

Yet whatever his own view in this regard may have been, the most important conclusion is that he certainly argued from the point of view of his analysis of language that we cannot speak about this. Famously, the final sentence of the Tractatus demands that ‘what we cannot speak about we must pass over in silence.’

We have here, then, in an extreme version the traditional idea of negative theology. Except that, you may remember, that tradition was by and large willing to allow God-talk in a particularly qualified way – through the use of negatives and through their negation it was felt God’s being could be approached even though the radical otherness of God meant that this could never be more than a feeble appropriation. Wittgenstein in the Tractatus would appear, then, from basis in the philosophy of language to arrive at conclusions very similar to those of a number of other post-Kantian thinkers, in theology and beyond, who all appear to draw on the tradition of the via negativa.

The question of course is whether the imperative of ‘remaining silent’ is conceivably realistic? It may sound paradoxical, but experience tells that to remain silent about anything is easier said than done. In fact, one may wonder whether the consequence from Wittgenstein’s insight, provided one accepted it, would not be that one had to learn to be silent on things concerning God. One might argue that the meditative journey chartered in Ps.-Dionysius’ Mystical Theology has precisely this intent.

Be this as it may, Wittgenstein himself soon became disillusioned about the view of language underlying the Tractatus. One of the major reasons for that was that he increasingly became convinced that there was no way in which philosophy could replace ordinary language. The project described in the Tractatus rested on the assumption that philosophy would produce its own ideal language. Over time, Wittgenstein saw that as a blind alley. In order to achieve his idea of purging empty metaphysical notions by means of philosophy of language he now sought to provide an analysis of ordinary language.

The result of this work led him to his famous insight that the meaning of language is identical with the forms of human interaction to which it is attached. In his own words: ‘The meaning of a word is its use in a language.’ In this way the question about the meaning of language is turned away entirely from the traditional assumption that words primarily refer to or denote objects. Instead Wittgenstein now argues that language is one with human practice.

It is in order to explain this surprising move that Wittgenstein introduces the idea of language-games. He never offers a definition for them, but it seems clear that they offer contexts of communication that allow us to make sense of what someone says.

I cannot here go into the details of this fascinating theory of language, but it should be clear at once that it must have a considerable influence on the way religious language and, specifically, language about God is understood. At first sight, the consequences would once again seem highly problematic. I said earlier that one of the recurrent features in Wittgenstein’s early and late philosophy was his idea of exposing the emptiness of metaphysics. For the later Wittgenstein, this project was carried out by arguing that traditional philosophy would take formulations out of their language-game context and ask questions about them which within that context could never have arisen and are, therefore, irrelevant.

Thus, propositional dogmatics claiming to describe objective reality, for example, through the use of metaphysical predicates for God, cannot be justified if one accepts the philosophy of the later Wittgenstein. Yet perhaps theology is not utterly refuted here but rather rid of a burden? This would be the case if Wittgenstein would alert the theologian to the possibility that metaphysics encouraged a misinterpretation of the more foundational religious utterances about God. Perhaps, in other words, religious language is misunderstood if its meaning is sought primarily in reference to a transcendent reality, and it may be much more promising to understand it along the lines of a language-game?

Thinking about God along the lines of the later Wittgenstein then leads to a consciously non-realist version of theology. The most influential such version has been developed by the so-called Yale School of George Lindbeck and Hans Frei. Lindbeck in particular argued in his landmark book The Nature of Doctrine that the correct understanding of the doctrines of the church was neither the orthodox, propositional assumption that they refer to a truth ‘out there’ nor the modern, subjectivist interpretation that their truth lies in the subjective faith of the individual. Instead they describe something like a ‘grammar of faith,’ rules accepted by the community of Christians for their internal communication about their common faith.

We can at once see why and how this is a modern response to the challenges to belief in God. Religious belief is here generally denied a realistic interpretation. The point then in talking about God is not at all whether such a thing exists, but whether communication along those lines makes sense within a particular historical, social and cultural context. If this were the case, the entire debate about theistic belief would be ‘exposed’ – very much in a Wittgensteinian manner – as a mere misunderstanding due to failure to appreciate the real meaning of religious language.

The question of course is whether it is the case, and even whether such a theory can claim the support of the late Wittgenstein. For it seems clear that for quite a number of language-games, external references are crucial – while talking about money only makes sense insofar as people are part of a particular economic system where this is known and recognised, it is equally clear that the point of discourse about money is that one either has it or has it not. Similarly, it would seem difficult to deny that the reality of religion depends on the willingness to believe that faith in God is more than a social or cultural reality. The problem with Lindbeck’s theory is that is can only work if believers don’t know about it, and this for a theological theory simply is not good enough.

I had said initially that the prevalence of language as a philosophical topic in the 20th century resulted from the unexpected convergence between two very different traditions. We have looked at one, specifically at the earlier and the later Wittgenstein. The other of course is the continental development of hermeneutics.

Why did hermeneutics lead to a new understanding of language? Originally, hermeneutics was merely a tool within disciplines that needed to apply traditional texts in new situations, mainly theology and law. It addressed the question that came after dogmatics: once we know what the ideal meaning of the text – be it a legal document or the Bible – is, how do we apply it correctly in a law case or in a sermon?

This was a limited and concrete task, but from the early 19th century hermeneutics was expanded to explain quite generally what it meant to understand any text within a situation that clearly was no longer the one in which the text had been penned. And from there it was only one step to expand the discipline even further by asking how it is possible that that great text around us, the world, makes any sense to us?

On the basis of this broadening of the hermeneutical horizon it was inevitable that language again became a focal point of philosophical enquiry. And as in the thought of Wittgenstein, this particular way of looking at the working of language made more traditional assumptions seem problematic.

Yet the difficulties with those traditional approaches arose less in relation to their supposed metaphysical abuse of language; it was more the limitation of language to a mere tool that seemed increasingly unhelpful for an understanding of what language really meant. Hermeneutics shaped the awareness that language was the gate connecting human beings with the world around them, and understanding what it was therefore became tantamount to understanding what human beings themselves are.

It is for this reason that 20th century interest in hermeneutics in both philosophy and theology is never far away from the concern with existence, which I discussed a few weeks ago. Hermeneutical theology, at least in one of its guises, was very much existential theology because of this intimate link between human abilities to interact with the world through their language and their basic identity as human beings.

I shall leave to one side here the existentialist hermeneutics of Bultmann and of the early Martin Heidegger, however. Instead I shall look at two major figures from the latter half of the 20th century who have contributed importantly to our understanding of language in relation to the theological task of speaking about God, Paul Ricoeur and Eberhard Jungel. While the former is a philosopher and the latter a theologian, both share a number of fundamental interests relevant for our topic here. Not least, both have developed their views about religious language and its importance for theology from studying the Bible – Jungel’s first works were exegetical in character, and Ricoeur has devoted specific work to the task of biblical interpretation.

Why is this relevant? Both, Ricoeur and Jungel start from an interest in the metaphorical language Jesus evidently uses in his parables. What does this practice tell us about his message, and how can a better understanding of language be of any use in that regard? The traditional view of the parables, developed essentially by Aristotle, was that metaphors are rhetorical figures. In other words, they do not contribute to our grasp of the matter, but embellish a given narrative. This they do by conjoining two seemingly unlike words, and this conjuncture makes sense because of a tertium comparationis, which is a quality that both have in common. So, if we call Achilles a lion, we don’t mean to say that he walks on four legs, has a fur and roars, but that he is particularly strong and brave. These qualities are, as it were, transferred from the lion onto Achilles (metapherein).

Note that according to this theory the metaphor does not add anything to our knowledge of either of the two objects. It does not tell us anything we don’t know yet; this is why, according to Aristotle, it is a rhetorical device. Into the early 20th century Jesus’ parables were essentially understood in this same way. Yet both Ricoeur and Jungel disagree. Both suspect that metaphors do much more than embellish speech, and both believe that their use in the New Testament is an important indicator of this fact. Let us look at Ricoeur first.

We have to remember that he writes as a philosopher. His interest is the interpretation of texts in general though he is quite willing to believe that the biblical texts are something special (and he was quite happy I think to be considered half a theologian). Still, for him the question is initially framed as a philosophical one: what does it mean to understand a text? Several possibilities seem to exist: it could simply mean to decipher the words used in this text. Alternatively, one could seek to go behind it and understand the psyche of the author. Trying to understand the text would then, ultimately, be a psychological task of understanding the person who produced the text.

Yet Ricoeur thinks the latter is useless and the former at best a first step. Much more interesting, according to him, is the interaction that ensues from reading a text between the text and the reader. For the recipient, the text constitutes what he calls a ‘text-world,’ which invites, but also challenges. It makes us desirous to become part of this world, but it is also clear that we need to change for this to happen. Ricoeur believes that quite generally, for a text to become meaningful, it needs this interaction with the reader, and this interaction involves a transformation of the person who exposes himself or herself to the text. This, however, means – and you may begin to see how this becomes theological – that texts that are read create new reality. A new world comes into being ‘before the text’ as Ricoeur says through the interaction between the text and its recipient; and the latter is actively involved in the realisation of this new reality.

What does this have to do with metaphor, and where does theology come in? Evidently, the moment the function of a text is seen in such a fundamentally ‘creative’ way, it seems attractive to ask whether not metaphor itself is more than merely a figure of speech. Much rather, it would appear to be a powerful tool precisely for the transformation of reality that is envisaged in every interaction between text and reader. And it seems to follow from there that in the special case of religious language that seeks to reveal an utterly new reality – the Kingdom of God which Jesus said had come near – metaphor will be of fundamental and crucial importance because of its ability to create new reality.

Interestingly, if we recall at this point some of the ideas of the later Wittgenstein about language we can see that they are not utterly different from what Ricoeur is after. For both see that language is about more than a reference to reality; it plays a role in a communicative process. For Ricoeur this process is primarily the process between text and reader, but this can obviously be broadened to include other instances of communication.

The major difference then seems to be that for Ricoeur the relationship between language and external reality is reintroduced with a remarkable twist. For it is no longer simply the case that language mirrors reality, but through its role in the communicative process language creates reality. This of course is well known to all of us as fiction, but Ricoeur would insist that this cannot be written of simply as an invention of some fantastical pseudo-reality, but it is the foundation ultimately, of God’s eschatological revelation, and it is, not least, an explanation of why such a revelation could have been possible in a book in the first place.

Eberhard Jungel shares a number of insights with Ricoeur, but as a theologian asks directly what contribution the study of language can make to our understanding of God. His major work God as the Mystery of the World is ultimately nothing other than an attempt to answer this question. Put simply, his argument is that the metaphysical idea of God, which theology adapted for a long time and which tried to find God behind the world of our experience had to lead to the gradual disappearance of God as we have witnessed it over the past two hundred years. Thus, his argument is very much shaped by the main challenges of modernity – the subtitle of his book characterises it as the search for the foundations of a theology of the crucified in the debate between theism and atheism.

Jüngel thus traces the rise of atheism and tries to understand this development ultimately as arising from a misconception of what God is: God as actuality without potentiality; God as an unchangeable substance – all these and other traditional notions of God fail to conceptualise the God of whom the Christian faith speaks.

It is as the alternative to this story of decline that he brings in the role of metaphorical language, not least in the preaching of Jesus. Christ, he thinks, was sent as the Word of God, and this is expressed precisely in the words he spoke. The parables contain words creative of a new reality, a reality that crucially involves the believer – we see how closely this meets with Ricoeur’s ideas. And it is because of this ‘coming of God into human language,’ which Jüngel thinks is ultimately what the Incarnation is all about, that the old problem of negative theology can be laid to rest.

His book contains a lengthy chapter on the tradition of the via negativa the upshot of which is that it is oblivious of the Christ event: is not the whole point of the Incarnation that God became human, and if this is the case who can it then still be appropriate for Christians to see him as remote and ‘unspeakable’?

We see here, at the end of today’s lecture, a conclusion arrived at that is diametrically opposed to that suggested by Wittgenstein’s argument in the Tractatus. While the early Wittgenstein had permitted at the utmost an extreme version of negative theology, Jüngel seems quite sanguine about the use of language for God. Of course, both have very different views about what God is and of what it means to speak about him.

For Jüngel, the point is to find God in the world, not in any shallow liberal way, but in the sense that the message of the gospel speaks of a transformation of this world through the good news of Christ’s coming. God then is precisely not an object on the margins of our intellective capacities or altogether beyond their reach. The point is not so much an asceticism of language, but its ethical adaptation to the possibility that the world before us is capable of change in the light of God’s revelation.

The question here may be what separates this from a liberal affirmation of the world as it is and its interpretation under the category of progress? Jüngel clearly does not want to go down this avenue, but in order to avoid it, does he not ultimately need the notion of God’s transcendence and remoteness because without those the notion of God and that of the world will inevitably collapse into each other?

Johannes Zachhuber is Professor of Historical and Systematic Theology at the University of Oxford. He is a Fellow of Trinity College. He earned his DPhil from Oxford in 1998 and obtained a habilitation in systematic theology at Humboldt University, Berlin, in 2011. His areas of specialisation include the history of Christian thought in late antiquity and the nineteenth century; secularisation theories; and religion and politics. He has authored or co-authored five books and edited or co-edited nine. He has written many articles and book chapters in all his research specialisations.