The following is the first installment of a three-part series.

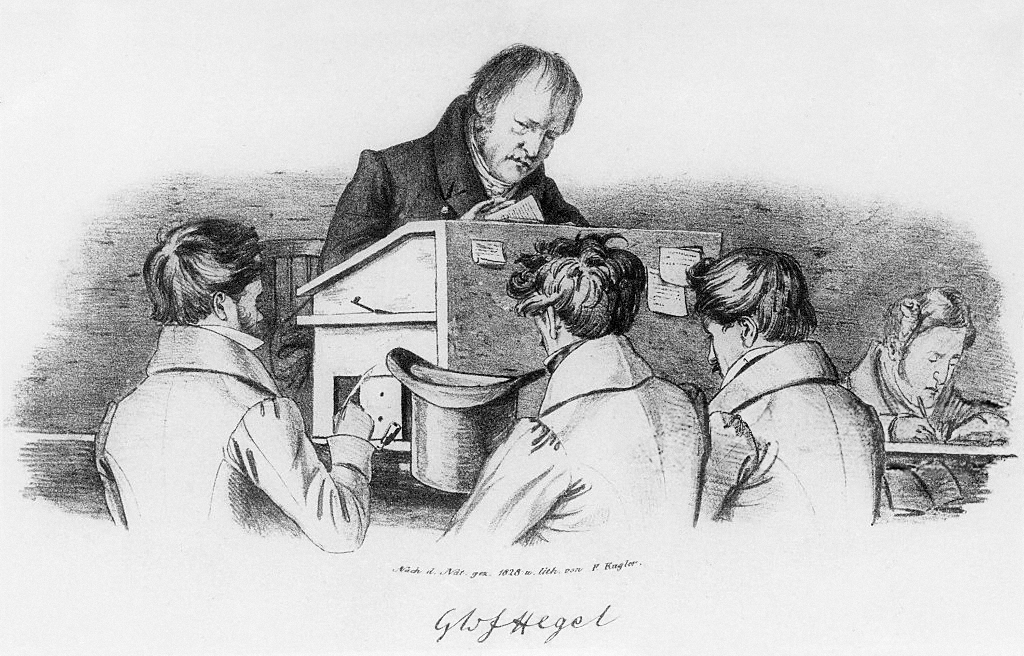

Among recent developments in continental philosophy and religious thought, one of the most prominent has been a ‘return to Hegel.’ It has been exemplified in the work of Slavoj Žižek, Beatrice Longuenesse, Catherine Malabou and Rebecca Comay, as well as that of a younger generation of scholars, such as Vincent Lloyd and Marika Rose.

Many of these thinkers draw on the work of Gillian Rose (in whom there has been a renewed interest), as do theologians Rowan Williams, Andrew Shanks and Joshua Davis. Without wishing to minimise the differences between these heterogeneous thinkers, it may nonetheless be said that their readings of Hegel partake of a ‘family resemblance’, and that they may collectively be characterised as constituting a ‘new’ reading of Hegel.

These reading may justifiably be characterised as ‘new’ in relation to ‘older’ readings against which they react and define themselves, and we may identify two in particular. First, there are the readings propounded by the postmodernists (but by no means only by them). These thinkers, Derrida, Levinas, Adorno, Deleuze and Bataille foremost among them, created or restored a ‘metaphysical’ Hegel who, in Robert Pippin’s phrase, served as these philosophers’ ‘whipping boy,’ an antithetical foil against which they defined themselves.[1]

This was what has become known as the ‘textbook’ or ‘cliché’ Hegel, a caricature our ‘new’ readers believe to be far removed from what is warranted by Hegel’s own texts. This is a Hegel who might indeed incorporate negativity and negation into his system, but for whom such negativity is always penultimate, always giving way to a higher unity, so that nothing is lost and nothing falls outside Hegel’s all-consuming System. This is a Hegel too who represents the apogee of modernity’s omniscient aspirations. His all-seeing System, crowned with the concept of Absolute Knowledge, seems to deliver modernity’s totalising dream. It appears to be a ‘God’s eye view’ recast in the terms of a secularised modernity, to which all is subordinated, and in light of which all is intelligible.

Secondly, there are the interpretations characterised by Žižek as the ‘deflated’ or non-metaphysical Hegel, and propounded by such thinkers as Robert Pippin, Robert Brandom, Terry Pinknard and, more recently, Thomas A. Lewis. These readings are, in many ways, the polar opposite of the metaphysical readings in that they ‘deflate’ Hegel’s metaphysical pretensions, such that Hegel’s thought, properly read and interpreted, is evacuated of metaphysics, and instead comes closer to a version of Kant’s transcendental idealism or to a version of a social rationality pragmatism.[2]

For our ‘new’ readers of Hegel, both of these ‘older’ readings – the ‘metaphysical’ and ‘deflationary’ – are alike mistaken. Rather, they insist that the true significance – and, indeed, radicalism – of Hegel’s thought lies in his attempt to find a way beyond both of these stances. Although, as we shall see, the ‘New Hegel’ thinkers identified at the outset are many and various and by no means expound a single vision, they would nonetheless agree with Žižek to the extent that he seeks to rescue Hegel from the charges that he purveys a ‘totalising rationalism,’ and that he enacts a philosophy of reconciliation that is unable to do justice to the particularities and contingencies of life.

As Robert Pippin has observed in relation to these two charges, ‘Žižek’s ambitious goal is to argue that the former characterization of Hegel attacks a straw man, and that, when this is realized in sufficient detail, the putative European break with Hegel in the criticisms of the likes of Schelling, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Deleuze, and the Freudians, will look very different, with significantly more overlap than gaps, and this will make available a historical diagnosis very different from the triumphalist one usually attributed to Hegel.’[3]

At the same time, our ‘new’ interpreters of Hegel want to resist the ‘deflated’ image of Hegel ‘freed of ontological-metaphysical commitments, reduced to a general theory of discourse, of possibilities of argumentation.’[4] To interpret Hegel in a ‘deflated’ as opposed to a metaphysical way is to remain caught in the dualism that Hegel was seeking to overcome. The challenge, for these readers, is to understand how Hegel is able to encompass the metaphysical and the non-metaphysical, the transcendent and the immanent, the necessary and the contingent, without relapsing back into the very dualism he sought to escape. Hegel’s significance for these thinkers lies in his being able to account for these distinctions in a non-dualistic way.

But what does this ‘new’ reading of Hegel entail for the question of God? There have been many works considering Hegel’s philosophy of religion and his conception of God over the last century. More recently, thinkers such as Peter Hodgson, Cyril O’Regan and William Desmond, to name just three, have all considered these questions in detail. But, as Thomas A. Lewis has observed, they assume interpretations of Hegel’s philosophy that are, in important respects, significantly different from the interpretations that have appeared more recently.[5]

Lewis himself considers the question of God from the perspective of the ‘non-metaphysical’ Hegel espoused by Pippin and Pinknard, in which line of interpretation Lewis locates himself. The question of what the ‘new’ interpretations of Hegel entail for God has been given much less sustained attention. It is nonetheless a question that is worth asking, not least because many aspects of the ‘new’ interpretation would, on the surface at least, seem to sit ill at ease with most orthodox conceptions of God. According to the ‘new’ interpreters, Hegel does indeed employ notions of necessity, unity, teleology and absolute knowledge, but, crucially, he radically reinterprets them in a way that stands in sharp disjunction to the way such notions are usually philosophically understood.

We must therefore ask to what extent a similar operation is enacted in relation to Hegel’s understanding of God. Given that Hegel does indeed commit himself to ‘the exposition of God as he is in his eternal essence’, how exactly does Hegel understand this God, according to the ‘new’ interpreters? And how is this conception related to the God of Christian orthodoxy? Could it be the case, as it was for the notions of teleology and ‘absolute knowledge’, for instance, that Hegel radically reinterprets the concept of God so that it becomes something markedly different to what has conventionally been supposed?

It would be a mistake to suppose that our ‘new’ readers of Hegel speak with one mind on these questions. For one thing, some of them give more attention to the question of God than do others. Thinkers like Beatrice Longuenesse, Judith Butler and Rebecca Comay give it scant attention, while others, such as Slavoj Žižek, Catherine Malabou and Rowan Williams, have treated the question of God in Hegel at some considerable length.

Even among those who do give the question extended treatment, there is by no means unanimity in their assessment. There are, in fact, some marked divergences on the question. Thus, some of our ‘new Hegel’ readers, such as Rowan Williams and Andrew Shanks, understand Hegel as being broadly compatible with a theistic ontology and, indeed, read Hegel through the lens of such an ontology. In contrast, Slavoj Žižek and Catherine Malabou understand Hegel in terms of an ontology of immanence, even though they conceive of a continuing role for God and the transcendent, within and emerging out of such an immanent ontology.

What we see, therefore, is that the ‘new Hegel’ interpretation itself gives rise to both a theistic and atheistic reading of Hegel, even if these readings are themselves distinct from the traditional ‘left-wing’ (atheistic) and ‘right-wing’ (theistic) readings that were predicated on more philosophically ‘conventional’ readings of Hegel.[6] It will therefore be worth giving some consideration to these theistic and atheistic readings of Hegel that emerge from within the ‘new Hegel’ interpretation itself.

To this end, I shall first look briefly at the readings of Rowan Williams and Slavoj Žižek, as being representative of the theistic and atheistic positions, which both emerge from philosophical readings of Hegel that share much in common, even if they are not identical. I then want to argue that these contrasting conceptions should not be viewed as mutually exclusive alternatives between which we must choose. Neither should we view them as readings that should be overcome and superseded by a third conception.

Rather, I want to suggest that both are necessary and should be held in tension. Furthermore, I want to argue this on specifically (new) Hegelian grounds. In other words, I shall conclude that a genuinely Hegelian conceiving of God will insist on the simultaneous necessity of both the theistic (Williams) and atheistic (Žižek) readings. I therefore want to suggest that a (new) Hegelian conceiving of God reveals once again the necessity of the logic of the both … and.

I

Rowan Williams’s writings on Hegel in general and on Hegel’s understanding of God in particular, are small in quantity, but rich and suggestive in quality. Like other ‘new’ Hegel interpreters, he sees the ‘starting point’ of Hegel’s project as being the enactment of a self-reflexive contemplation or meditation on the character of thought itself. Much of Williams’s reading of Hegel in this respect coincides with what others emphasise as being central to Hegel’s thought.

But he specifically wants to draw attention to the way in which such a reading of Hegel becomes impoverished if it is not orientated towards a theological point of reference in the way that Hegel himself orientated it. In a lengthy passage that is worth quoting in full, Williams shows how what Hegel speaks about philosophically is said religiously by the language of theology:

‘Dialectic is what theology means by the power of God, just as Verstand is what theology means by the goodness of God. Verstand says “Everything can be thought”, “nothing is beyond reconciliation”, every percept makes sense in a distinctness, a uniqueness, that is in harmony with an overall environment. It is, as you might say, a doctrine of providence, in that it claims that there can be no such thing as unthinkable contingency. But … thinking the particular in its harmonies, thinking how the particular makes sense, breaks the frame of reference in which we think the particular. God’s goodness has to give way to God’s power – but to a power which acts only in a kind of self-devastation. And, says Hegel, the “speculative” stage to which dialectic finally leads us is what religion has meant by the mystical, which is not, he insists, the fusion of subject and object but the concrete (historical?) unity or continuity or followability of what Verstand alone can only think fragmentarily or episodically.’[7] In other words, much of what is most distinctive and original about Hegel’s philosophy coincides with what has already been said by theology.

But this, in itself, of course, does not necessarily lead us to place Hegel’s thought within the context of a theistic ontology. It might also be compatible with some of the ‘immanentist’ readings, and the theological reference might also be ‘superseded’ if it is regarded as merely penultimate a piece of window-dressing that must finally give way to the higher truth of (a secular) philosophy. Williams explicitly denies these possible readings, saying that ‘it is precisely the grammar (including the paradoxes) of classical pre-Cartesian theology that shapes the actual structure of thinking about thinking.

To think about thinking must, for Hegel, bring us finally to the point to which theology directs us, to a reality that is determined solely as self-relatedness: the grammar of the God of Augustine, Anselm and Aquinas is the grammar of thought, and without the former the scope of the latter could not be apprehended.’[8] So what Williams is suggesting here is that the grammar of theology is what allows or enables the truths of philosophy to appear; we would not be able to perceive the speculative truth of philosophy outside the light of the divine truth of theology.

Williams has a great deal more to say about why, according to Hegel, theology must speak of the simplicity of God, but why God must also be understood in terms of narrative and movement; and why, ultimately, God must also be understood in Trinitarian terms, with all that this implies for Incarnation and pneumatology. These truths are not merely contingent, whether in the sense of being ‘thrown up’ by the contingent development of the tradition nor in the sense of being ‘sheerly’ contingent on divine revelation or the divine will. Rather, Hegel shows how they are, in a sense, necessary, if they are to reflect what it genuinely means for thought to think itself in community.

But while it might be possible to say all this, still the question remains as to whether one could make all these claims while still simultaneously that it is possible for religion to express pictorially what are ultimately philosophical truths. Even if the religious narratives are necessary, in the way Williams suggests, for philosophical truths to be perceived, once the latter have indeed been perceived, are the religious narratives thereby not understood in a new way that is distinct from their own self-understanding? More specifically, could it not be said that what for theology’s own self-understanding was a ‘transcendent’ reality, we can now see, having attained the insights of philosophical truth, that what they gestured towards was, in fact, an ‘immanent’ reality?

Although Williams doesn’t directly and explicitly confront this challenge, we can glean, from his what he says more generally, the contours of his likely response. In particular, it is likely that he would want to question the dichotomy or dualism that is being presupposed here between ‘transcendence’ and ‘immanence’. We get a sense of this when Williams says the ‘basic structure of spirit is not dependent on, or a fact in, “the world”: it is what it is, identity, otherness, reconciliation.

Because this is what mental life is, we can’t think it apart from thinking ourselves; to think it as separate is to fail in thinking-as-such.’[9] We see from this, therefore, the extent to which Williams wants to move away from an exaggerated sense of the separation between God and the world. Indeed, he makes this point in the context of responding to theological critics who accuse Hegel of asserting an interdependence of God and the world, and therefore of neglecting God’s self-sufficiency. Such a criticism, he suggests, is still working with a model of separation; it is said that God is interdependent precisely because it is assumed that there are two discrete and identifiable entities which can be in a relation of interdependence.

At the same time as wanting to question this exaggerated sense of separation between God and the world, Williams also wants to resist an undue identification of God and the world, of which Hegel is also sometimes accused. As Williams observes, God is not thought ‘if God appears as merely identical with the world’s process: this would leave the world with an unmediated identity, and God as non-subjective or pre-subjective reality, and therefore not in the strictest sense thinkable – i.e. God becomes inferior to the thinking mind, something that has to be connected with and reconciled with mind so as to be thought; and the idea of a universal “substance” that is pre-subjective is a nonsense in Hegel’s terms, since what is pre-subjective cannot be universal.

Hegel’s repudiation of charges of atheism is profoundly serious.’[10] So Williams is committed to treading a very fine and precarious line – and it may be said that he is being faithful to Hegel in doing so – in wanting to resist both an undue separation between God and the world and also an unwarranted identification of God with the world.[11] This perilously fine line is well articulated when Williams seeks to combine a sense of God’s aseitas or self-sufficiency with a proscription of thinking of God as an ‘object’ for thought, as somehow being ‘beyond’ thought: ‘ “But”, we ask impatiently, “would there be a God if there were not a world?”

And Hegel simply refuses us the vocabulary and conceptuality to put such a question intelligibly. Insofar as God is the ungrounded or self-grounded reality without which there is nothing thinkable (and therefore nothing, if we seriously understand who and what we are), we can indeed deploy the traditional language of aseitas. Yet that reality is such that it refuses to be an object for thought, a life lived “beyond” us that we can yet talk about. God’s “exceeding” of thought cannot itself be thought or spoken’.[12]

In light of this very precarious tightrope walk, we may well wonder whether this kind of theology can really be described as one of ‘transcendence’ at all, at least in the commonly understood sense. To which it might be replied that it was precisely Hegel’s aim to trouble the traditional distinction between transcendence and immanence, and to think of Spirit in terms that transcend the traditional distinction between transcendence and immanence. It should also be pointed out that Williams does not necessarily commit himself to Hegelianism tout court. He has said that his aim in writing about Hegel ‘is not to endorse the Hegelian system in all its ambition and complexity’[13]; rather, his aim has been to pose questions to theologians in order that they may consider the adequacy of certain ways of doing theology, in the ongoing task of thinking about God. Nonetheless, what we can see from this brief discussion of Williams’s understanding of at least the compatibility of Hegelianism, properly understood, with the orthodox tradition, properly understood, is that the sense of God’s ontological transcendence, while retained, is one that at least troubles and questions any straightforward opposition between transcendence and immanence.

Gavin Hyman is Senior Lecturer at the University of Lancaster. He is the author of The Predicament of Postmodern Theology: Radical Orthodoxy or Nihilist Textualism (Westminster John Knox, 2001), A Short History of Atheism (I.B. Tauris, 2010), and Traversing the Middle: Ethics, Politics, Religion (Cascade Books, 2013).

_________________________________________________________________________

[1] Robert B. Pippin, Hegel’s Idealism: The Satisfactions of Self-Consciousness (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), p. 4.

[2] These are Adrian Johnston’s terms. He has suggested that Pippin has himself moved between these different versions of a ‘deflationary’ reading of Hegel. See Adrian Johnston, ‘Where to Start? Robert Pippin, Slavoj Žižek and the true Beginning(s) of Hegel’s System’, Crisis and Critique 1 (2014), p. 376.

[3] Robert Pippin, ‘Back to Hegel?’ Mediations 26.1-2 (Fall 2012-Spring 2013), p. 8.

[4] Slavoj Žižek, Less than Nothing: Hegel and the Shadow of Dialectical Materialism (London: Verso, 2012), p. 237.

[5] Thomas A. Lewis, Religion, Modernity and Politics in Hegel (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), p. 11 and n. 25. See also Thomas A. Lewis, ‘Beyond the Totalitarian: Ethics and the Philosophy of Religion in Recent Hegel Scholarship,’ Religion Compass 2 (2008), pp. 556-74.

[6] For a classic discussion of this taxonomy, see Emil L. Fackenheim, The Religious Dimension in Hegel’s Thought (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1967).

[7] Rowan Williams, ‘Logic and Spirit in Hegel’ in Wrestling with Angels: Conversations in Modern Theology, ed. Mike Higton (London: SCM Press, 2007), pp. 37-38.

[8] Ibid., p. 38.

[9] Ibid., p. 47. My emphasis.

[10] Ibid., pp. 40-41.

[11] On this theme in Augustine’s thought, see Rowan Williams, ‘”Good for Nothing?” Augustine on Creation,’ Augustinian Studies 25 (1994), pp. 9-24.

[12] Williams, ‘Logic and Spirit in Hegel’, p. 47.

[13] Rowan Williams, ‘Hegel and the gods of postmodernity’ in Wrestling with Angels, p. 31.