There is no reason why therapy rooms for psychedelic sessions must be adorned with the default Buddha icons, fractal posters, and Indian drapes. Who says these are the hallmarks of psychedelia? Why not have pictures of Lamborghinis, pop stars, and football teams – or any other power objects our patients choose to bring? -Ben Sessa[1]

I must begin with a few terminological distinctions. The first distinction I need to make is that we need to have a critical separation between what some people call “non-ordinary” states of consciousness and “altered states,” or “shamanic states,” etc.

This distinction, which involves issues of cultural competence and cultural humility, often goes unacknowledged with respect to psychotherapeutic models used with psychedelic treatment. Such terminological distinctions bring with them a deep framing imbricated in hierarchical and colonial thinking by assuming that there is a normative or “ordinary state.” Stanislav Grof has noted these terminological problems and introduced the term ‘holotropic’ or “moving toward wholeness.”[2]

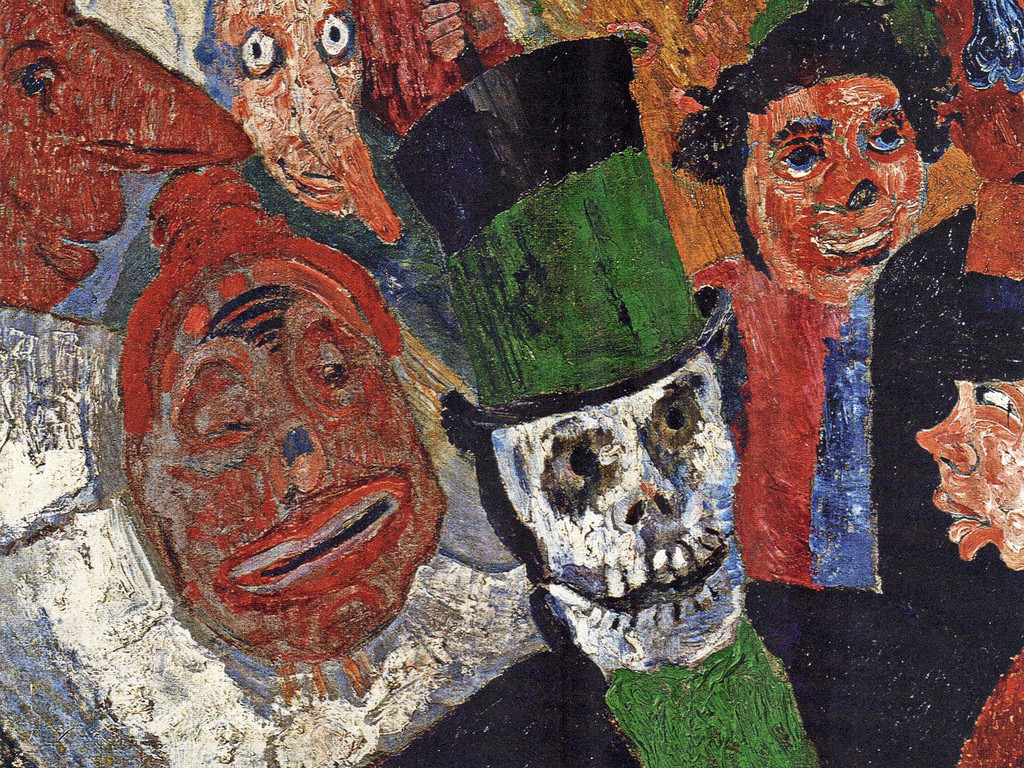

I use these terms because they signal the historical nature of the problem I am addressing by asking: does the cultural-historical place that psychedelics occupy within “western” culture affect the intentional framing of set and setting in psychedelic therapy? I think it does, and I argue that, while admirable, the rhetorical efforts to deregulate psychedelics for therapeutic research often mask uncritical assumptions about both psychedelics and the unconscious. More than just words, the frames we develop around emergent psychedelic therapies will be crucial in medicinal practices.

A second distinction I want to be clear about intensifies my argument: historically, entheogens have not always been necessary for doing work in different “planes of consciousness,” “worlds,” “dream times,” etc., and when entheogens have been used, they have not psychedelic substances used as entheogens. Within discourse on psychedelics, language and naming has been an ongoing problem since Humphry Osmond coined the term in his letter to Aldous Huxley in 1957 in their attempts to replace the term ‘psychotomimetic.’

As is well known, ‘psychedelic’ means “mind-manifesting” and rests on common assumptions that there is something called “mind” to be manifested. The Freudian conception ought to be evident from the distinction of latent and manifest, thus framing discussions about psychedelics within a concept that they act to “unleash” or “emerge” or “make aware” the unconscious. ‘Entheogen,’ a term coined by Carl A. P. Ruck and R. Gordon Wasson, et al. in the late 1970s, carries obvious theological baggage with the Greek cognate ‘theo’ in the western tradition.

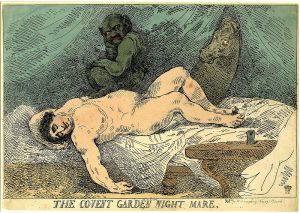

With respect to the associations that LSD in particular had with mimicking psychosis, Charles Nichols notes that

The first scientific report proposing that the behavioral effects of intoxication by LSD resembled psychosis was published in 1947 (Stoll, 1947), the same year that LSD was made commercially available by the Swiss pharmaceutical company Sandoz. LSD was sold under the brand name Delysid and marketed as a tool for potential psychiatric treatment. Some sources have reported that Sandoz recommended that psychiatrists take the drug to “gain an understanding of the subjective experiences of the schizophrenic” (Ulrich & Patten, 1991).[3]

Few people are aware of the fact that before psychedelics such as LSD and psilocybin were made illegal in the United States, early clinical models of psychedelic therapy were “preceded by many hours of preparatory psychotherapy and require[d] a trained and experienced guide to handle all the complications that might occur.”[4] The model of the doctor taking the psychedelic substance with the patient while a nurse remained present at hand for emergencies had its roots in 19th century scientific practices where it was common for scientists to experiment by using their own bodies.

We see this practice in aesthetes as well, from Charles Baudelaire’s Artificial Paradises to

Walter Benjamin’s writings on hashish, but it especially came into use after Aldous Huxley convinced Timothy Leary, Ralph Metzner, and Richard Alpert to “translate” the Tibetan Book of the Dead as The Psychedelic Experience. Even this, as Donald Lopez has noted, was filtered through the already theosophical agenda of Evans-Wentz’s translation if The Tibetan Book with one of its introductions by C. G. Jung.[5] Little work has been done to unpack the problems of cultural framing throughout the 20th century with respect to the political theological conundrum psychedelics came to occupy.

We could also raise a more practical issue: can anyone imagine spending that much time with any one physician in current healthcare models in the U.S.? What existing inequities with respect to healthcare are perpetuated by the experiential time it takes to do psychedelic therapy? The shared experience of the patient-doctor relationship was obviously dropped within clinical settings that have slowly been seeing deregulation of Schedule I substances for research purposes, but even in the well-known work of Rick Strassman’s work on DMT he affirms that “the nature of psychedelic work is highly collaborative.”[6]

Nicolas Langlitz’s research published in Neurpsychedelia stands as an exception. Langlitz, who was already a medical doctor did a second doctorate in anthropology, where his ethnographic work in labs testing LSD on human subjects allowed him to combine participant observation with psychedelic experience. Langlitz concludes that no matter how positivistic or “hard science” the methodologies were in the labs where he participated, the discussion of spirituality and God emerged from both patients and avowedly atheistic researchers, leading him to suggest that while the post 1960s research culture vilified the work of the early Harvard researchers and their exile to the Millbrook estate, they may have been onto something.[7]

Still, the methodological taboo remains in scientific circles, even though William A. Richards claims in his recently published research from the Johns Hopkins psilocybin studies that psychedelics proof that God in some form exists.[8]

On the street and in illegal psychedelic therapy, the role of “guide” popularized by Leary et al.’s The Psychedelic Experience persists, especially in the popularization of ayahuasca ceremonies both in tourism and increasingly in yoga studios across the U.S.[9] Groups like MAPS (Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies) and their Zendo project at festival events like Burning Man also perpetuate the guide model along with the biopolitical rhetoric of becoming healthy to deregulate controlled substances.

Whether in recreational or clinical settings, however, one often sees entrenchment within the deep framing of liberal and western assumptions about the state of nature, metaphorically persistent in notions such as “the archaic revival” and “invisible landscape.” Many enthusiasts see themselves as critiquing “Western” culture through the use of psychedelics, so there is an ongoing tension between deep cultural critique and efforts to “legitimize” work with alternating states in Western medical practices.

For example, Ralph Metzner, despite his good intentions to critique the ills of Western culture, often describes psychedelics as giving access by which we might explore unknown continents – the final frontier of consciousness – mixed with language of revival. The acronym for MAPS is an obvious example, and Grof speaks of expanding the cartography of the psyche beyond the post-natal tabula rasa that characterized Freudian psychoanalysis.

Metzner writes, “the revival of animistic, neopagan, and shamanic practices, including the sacramental use of hallucinogenic or entheogenic plants, represents a reunification of science and spirituality, which have been divorced since the rise of mechanistic science in the seventeenth century.”[10] It is this mixed metaphorical framing of revival and “frontierism,” I argue, that operates to meta-frame the set and setting and cultural desire or motivation to explore consciousness as a psychonaut. Within that framing exist troubling conceptualizing of what the unconscious itself is. I hope here to parse some of the troubling conceptions out here through the work of Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari.

Deleuze and Guattari are of course themselves entrenched within western thought. However, through their anti-philosophy and anti-psychology – and in particular their overlapping efforts with transpersonalism in a larger European movement to develop non-Newtonian and non-fascist methodologies – they go further than most to critique it from within. Without resorting to either orientalism or the so often invoked fMRI scans of the brain that relegate research to a play of signs and images, Deleuze and Guattari describe the processing of thought itself.

With respect to the unconscious, Deleuze and Guattari claim that “drugs give the unconscious the immanence and plane that psychoanalysis botched.”[11] The mistake drug addicts make, Deleuze and Guattari suggest, is always to “start over again from ground zero, either going on the drug again or quitting, when what they should do is make it a stopover, to start from the middle.”

Writing in the 1980s, they argue that drug use is “over,” claiming that “drugs are too unwieldy to grasp the imperceptible and becomings-imperceptible; drug users believed that drugs would grant them the plane, when in fact the plane must distill its own drugs, remaining master of speeds and proximities.”[12] But it is useful according to them to contrast psychoanalysis and pharmacoanalysis. We might ask then, what the relationship is between the plane and the unconscious.

Writing in the 1980s, they argue that drug use is “over,” claiming that “drugs are too unwieldy to grasp the imperceptible and becomings-imperceptible; drug users believed that drugs would grant them the plane, when in fact the plane must distill its own drugs, remaining master of speeds and proximities.”[12] But it is useful according to them to contrast psychoanalysis and pharmacoanalysis. We might ask then, what the relationship is between the plane and the unconscious.

If psychoanalysis “botched” the immanence of the unconscious, it seems to have been two-fold. On the one hand, with respect to latency, “the plane of the Unconscious remains a plane of transcendence guaranteeing, justifying, the existence of psychoanalysis and the necessity of its interpretations.”[13] The power of analysis was mistakenly seen in its ability to sort out the troublesome past, to make “sense” of or to comprehend a clearer version of a narrative where sublimation could be seen in the repressive act of transferring desire from one object to another – Hitchcock’s Marnie, for example.

For Deleuze, this is a mistake because memory is the product of the present, not the past. From the plane of immanence we see “There is no longer a conscious-unconscious [Cartesian] dualism machine, because the unconscious is, or is rather produced, there where consciousness goes, carried by the plane.” But while drugs “give the unconscious the immanence and plane,” their causal line must be traced back to the “dealer” or apparatus. And then

What good does it do to perceive as fast as a quick-flying bird if speed and movement continue to escape somewhere else? The deterritorializations remain relative, compensated for by the most abject reterritorializations, so that the imperceptible and perception continually pursue or run after each other without ever truly coupling.[14]

I want to link this this flight that does not escape to the concept of re-entry from the psychedelic experience. As we know, returning from the Bardo plane means the liberation of the clear light did not occur.

On the other hand, Deleuze and Guattari, the unconscious manifests difference in its truly generative and creative form, willy-nilly. The true power of the unconscious is its ability to make all thought and identity ressentiment. Intentionality intends in the ways that early moderns described the eyes like headlamps extending out into the world. It traces its light to a point of origin.

Just as the term “will” in English is not the verb “to be” but the optative form of the Proto-Indo-European wel, which overlaps with the noun of “will” as an aspect of mind and the averb “well” literalized in a “wishing well” which is not just a hole with water but a spring, intention traces back to a dependent life, a life dependent on water coming forth, a life-giving spring — that is the unconscious. Even if one could “tap into” the unconscious the tapping is already the generation of the unconscious.

In Lacanian terms, the problem with reductive psychoanalysis is literally the denial of the Real. Desire is not the drive of a hunger that lacks but as Levinas says of goodness and metaphysical desire, “it nourishes itself, one might say, with its hunger.”[15] The unconscious drives us in our drives. We ought to understand from this why so many of Ovid’s and other poet’s metamorphoses involve springs, water nymphs, and birds with respect to the unconscious as springing forth and Deleuze’s connection of the unconscious with the differentiating principle of Nietzsche’s eternal return.

And just as so many people mistake the will to power as the manifestation of their own wishes, which is essentially what fascism is, others submit to the force of a larger social will – even Rousseau’s general will – and thus enter the stream of force as they perceive it. Even progressivism in its submission to an imaginary future and self-sacrifice enacts an intended dissolution of self, as if that self had control of itself.

This may certainly be why later Timothy Leary and psychologist Art Kleps (who broke away from Leary’s Millbrook group) gave up the guru-therapist model for “turn on, tune in, and drop out” and to “start your own religion.” While it is difficult to depoliticize this language from being a historical commonplace, both Leary and Kleps were actually moving beyond the political framing of their political moment in order to advertise more liberating models, the kind espoused revival of the term “cognitive liberty.”

“Cognitive liberty,” however, still assumes a matter of choice, and Charlotte Walsh has noted that despite appeals to the European Convention on Human Rights, “Rights-based claims revolving around religious and cognitive liberty are given short shrift.”[16] Even so, it is a maneuver away from the language of set and setting.

The very idea of set and setting is crucial to understanding psychedelic research and therapy. “Set” generally refers to what an individual brings to the occasion, including expectations (or lack thereof). “Setting” refers to the environment in which one comes to manifest the psychedelic experience. What is “conscious” / manifest about set and setting? Is it the intention of the doctor or the cultural assimilation of the patient into the doctor’s culture?

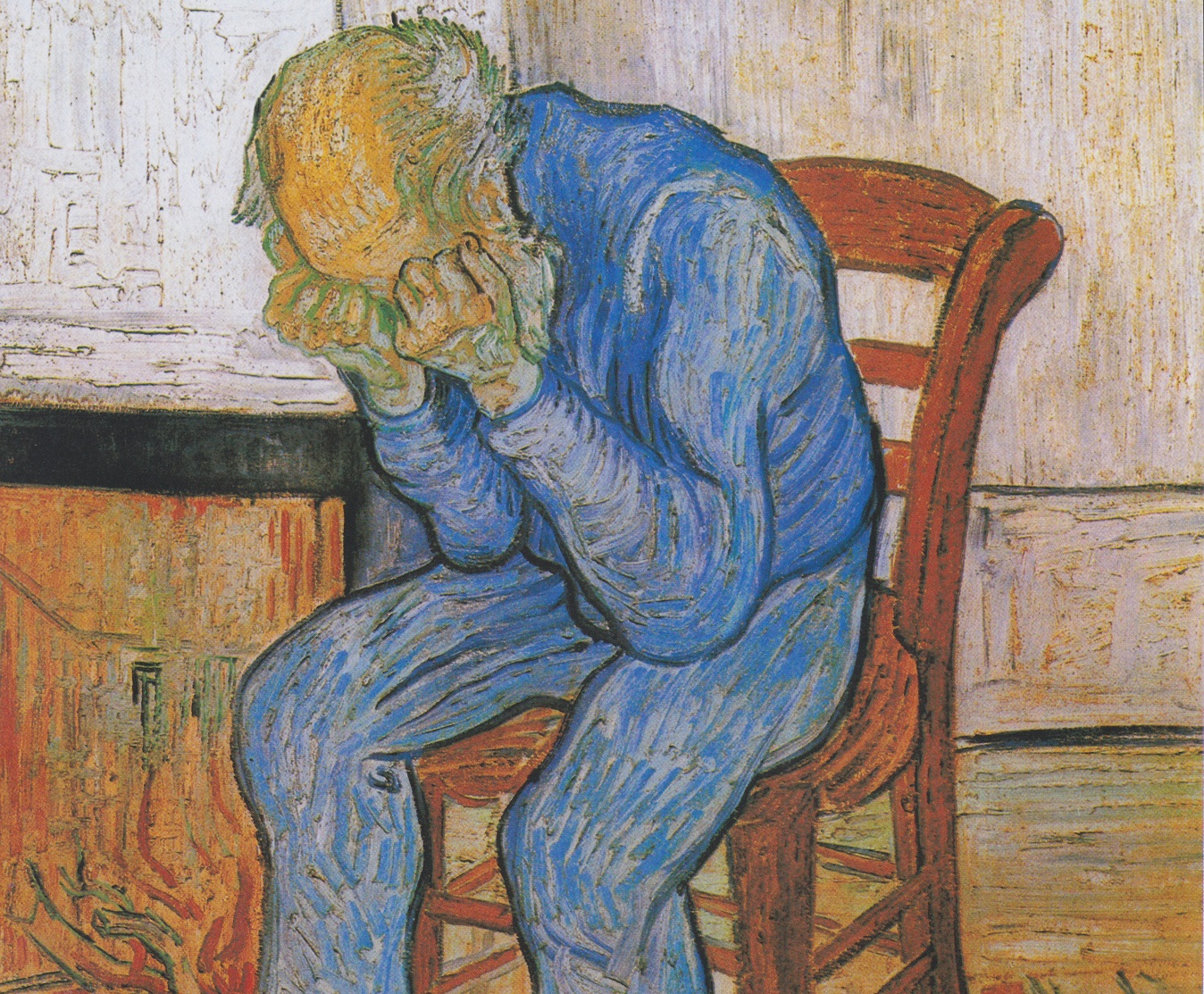

The great psychedelic research pioneer, Stanislav Grof, has suggested some specific changes that psychedelics bring to classic psychiatric and psychological models of therapy. First, he suggests that the Freudian cartography of human psyche postnatal biography was too limited. The Freudian individual unconsciousness is derivative of postnatal biography repression, memory, oedipal conflict, etc.

He believes that the psyche permeates all of existence, including prenatal experience and the memory of how we were born, something which transpersonal psychology’s emphasis on prenatal development has helped to correct. Grof notes how Jung helps psychedelic therapy by making psyche into anima mundi as well as Rudolph Otto numinous elements of psyche. From a therapist’s perspective, you cannot use your intellect understand existence or to “fix” the patient, but you can create a special alchemical environment where the conscious ego communicates with “S” between conscious ego and Self.

It follows from this that we must bring spirituality and religion back into therapy.  Psychedelic research therefore requires us to have a postsecular approach to spirituality in order to have good therapy. As in situations of extreme trauma, according to the transpersonal model, a psycho-spiritual death and rebirth process helps in cases where one has to reach back into prenatal or birth experiences to untangle the trauma.

Psychedelic research therefore requires us to have a postsecular approach to spirituality in order to have good therapy. As in situations of extreme trauma, according to the transpersonal model, a psycho-spiritual death and rebirth process helps in cases where one has to reach back into prenatal or birth experiences to untangle the trauma.

Moreover, according to Grof, transpersonal approaches can take you to any point in human history, regardless of culture, language, ethnicity, etc. Grof is optimistic about the reintroduction of psychedelic research because now we are accustomed to experiential therapies which did not exist in the 1960s. Again, I am reminded of the cartographic metaphors employed by Metzner and others.

As I have argued elsewhere,[17] the appeal to an “archaic revival” has potentially dark political implications. While many associate the psychedelic movement with the left in the U.S., its connection to far right politics can be seen in its European roots and thinkers involved with the Eranos group. When we neglect to study intellectual movements like Eranos and the traditionalist school, we have a limited perspective on psychedelics in history.

Instead, psychedelics get framed as anodyne and what affect theorist Lauren Berlant has called “cruel optimism.” As she says, “‘Cruel optimism names a relation of attachment to compromised conditions of possibility whose relation is discovered either to be impossible, sheer fantasy, or too possible, and toxic.”[18] The work of Deleuze and Guattari, largely contemporaneous with the psychedelic movement itself, may give us better ways to articulate the unconscious, psychedelics, and religion without using our wills to “recreate” Paleolithic landscapes by which we could somehow control the force of history, or what Carl Raschke calls The Force of God.

Roger Green, PhD, is a Lecturer in English who teaches composition and rhetoric at Metropolitan State University in Colorado. His recent professional work brings political theology into conversation with the field of aesthetics. He is the author of “Aldous Huxley, in the Aldous Huxley Annual: A Journal of Twentieth-Century Thought and Beyond (Ed. Bernfried Nugel and Jerome Meckier (vol. 14, 2014 / 2015) and several other related articles. In 2011 he received a certificate from the Cornell School of Criticism for the work he did with political theorist Victoria Kahn. He is also a performing musician and a composer.

_____________________________________________________________

[1] Ben Sessa, “Continuing History of Psychedelics in Medical Practice,” The Psychedelic Policy Quagmire: Health, Law, Freedom, and Society, Ed. J. Harold Ellens and Thomas B. Roberts, Santa Barbara: Praeger, 2015, 84.

[2] Sanislav Grof, “Implications of Psychedelic Research for Psychiatry and Psychology,” Conference presentation, Psychedelic Science in the 21st Century, April 15-18, 2010. https://vimeo.com/14191834

[3] Charles D. Nichols, “Chapter 80 – Schizophrenia Modeling Using Lysergic Acid Diethylamide,” Neuropathology of Drug Addictions and Substance Misuse, Ed. Victor R. Preedy, San Diego: Academic Press, 2016, 859-865. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-800212-4.00080-7

[4] Stanislav Grof, “History of LSD Therapy,” LSD Psychotherapy, Alameda: Hunter House Publishers, 1980. http://www.psychedelic-library.org/grofhist.htm

[5] Donald S. Lopez, Jr., Prisoners of Shangri-La: Tibetan Buddhism and the West, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998.

[6] Rick Strassman, DMT: The Spirit Molecule, Rocherster: Park Street, 2001, 123.

[7] Nicolas Langlitz, Neuropsychedelia: The Revival of Hallucinogen Research Since the Decade of the Brain, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013.

[8] William A. Richards. Sacred Knowledge: Psychedelics and Religious Experiences, New York: Columbia University Press, 2016, 211.

[9] Ariel Levy, “The Drug of Choice For The Age of Kale,” The New Yorker Magazine, Sept. 12 2016, http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/09/12/the-ayahuasca-boom-in-the-u-s

[10] Ralph Metzner, “Introduction: Vine of Visions,” The Ayahuasca Experience: A Sourcebook on the Sacred Vine of the Spirits, Ed. Ralph Metzner Rochester: Park Street, 2014, 5-6.

[11] Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, London: Continuum, 1988, 284.

[12] Ibid., 286.

[13] Ibid., 284.

[14] Ibid. 284-285.

[15] Emmanuel Levinas, Totality and Infinity: An Essay on Exteriority, Trans. Alfonso Lingis, Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press, 34.

[16] Charlotte Walsh, “Plant Psychedelics in English Courts,” The Psychedelic Policy Quagmire: Health, Law, Freedom, and Society, Ed. J. Harold Ellens and Thomas B. Roberts, Santa Barbara: Praeger, 2015, 315.

[17] Roger K. Green, “Archaic Revivals and Shamanism in the Liberal Global Imaginary,” The Psychedelic Press UK Journal, vol. 12, 2015. https://psychedelicpress.co.uk/products/psychedelic-press-uk-journal-2015-volume-iv

[18] Lauren Berlant, “Cruel Optimism,” The Affect Theory Reader, Ed. Melissa Gregg and Gregory J. Seigworth, Durham, Duke University Press, 94.