Caputo, John D., Moody, Sarah, and DeLay, Tad., It Spooks: Living In Response To An Unheard Call. Rapid City SD: Shelter50 Publishing Collective, 2015. ISBN-10: 0986249505. Paperback. 260 pages.

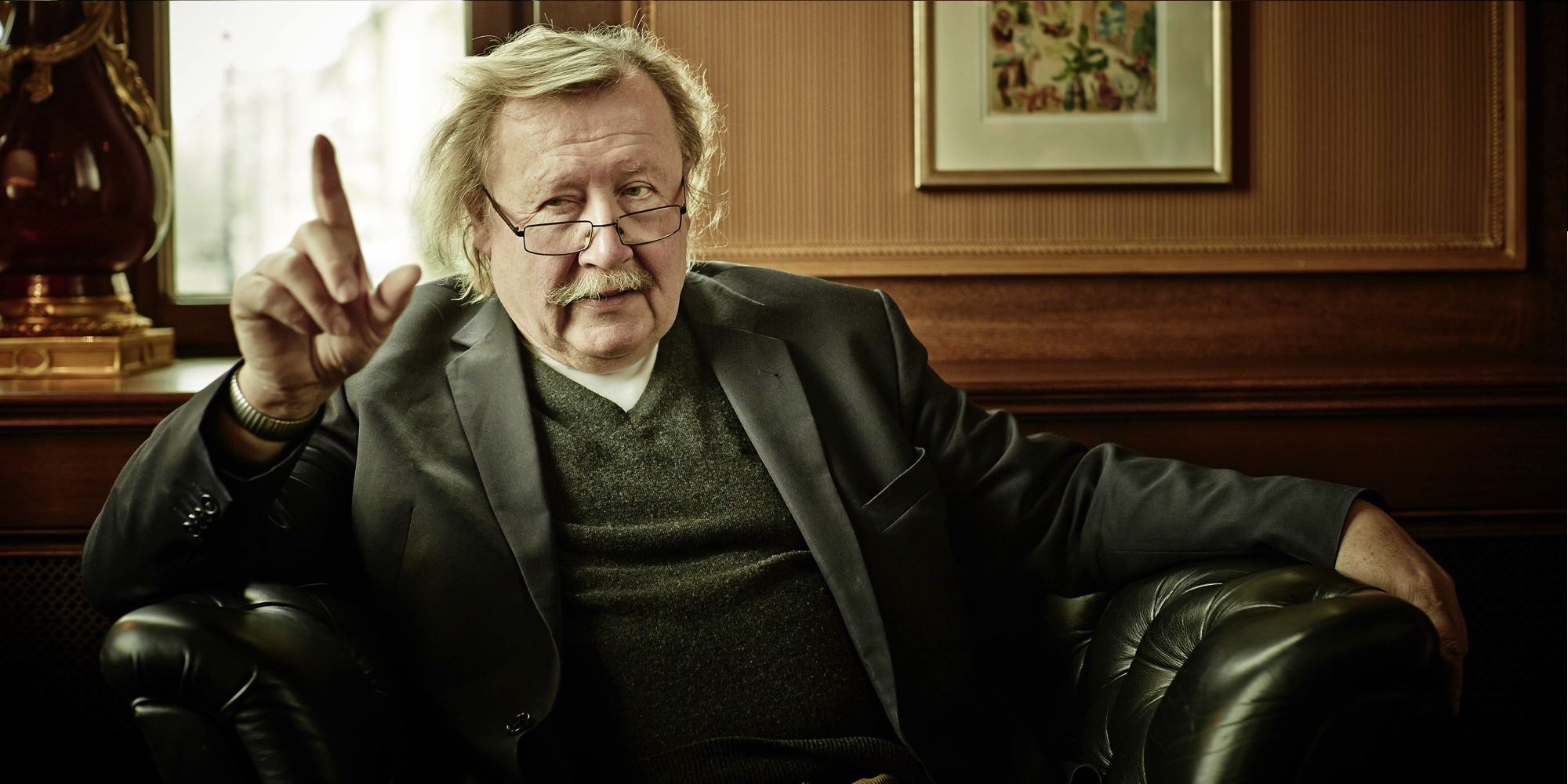

In It Spooks John D. Caputo continues his investigation into the theoretical possibilities of combining deconstruction with Judeo-Christianity. This time Caputo has brought along for the journey many sympathetic co-contributors in the guise of theorists, poets, visual artists, and experimental bricoleurs of text and genre. In general, the book is a nice assemblage of responses to Caputo’s call. The performative mood of the text is reminiscent of the literary expressions associated with Derrida’s middle period and auto-biographical writings. In this way, many of the pieces in this anthology are artistically creative and reflective of the idiosyncrasies of each contributor.

Most prominent of such a focus is Caputo’s interest in Derrida’s autobiographical excursions in his response to Geoffrey Bennington’s conceptualization of “Derridabase” in Circumfession. It is perhaps noteworthy that Caputo identifies Circumfession as the “pivot” around which his most foundational book The Prayers and Tears of Jacques Derrida revolves in trying to think of Derrida’s religion. In looking back to such theoretically driven performative interests, we can perhaps recognize the less conventional approach of Caputo’s most recent volume as exploring such familiar themes in a newly stylized and hospitable way. In a sense, this book is a natural evolution of Caputo’s theoretical works.

Caputo’s particular contribution is the essay “Proclaiming The Year of The Jubilee: Thoughts On Spectral Life”. At a length of around forty pages the essay provides a nice reassertion of the major tenets of Caputo’s most recent themes and terminologies. The notion of a “year of jubilee” is consistent with the kingdom terminology Caputo emphasizes in earlier texts, as the messianic insistence serving as promise or absolute future contra something that might exist in time.

Likewise, as the text’s title might suggest, special emphasis is also attributed to the illusive “if” at the groundless ground of Caputo’s radical theology, yet this emphasis does not expand upon Caputo’s earlier works. These earlier works incidentally go into more detail regarding exactly what the “It” of It Spooks is invoking and theoretically indebted towards. Its various conceptualizations and associations have changed expression over the years, and herein the “It” repackages the groundless ground of generation.

Caputo does mention Heidegger and Derrida briefly, but he has gone into greater detail elsewhere regarding what such theoretical antecedents he is invoking and its conceptual associations. Instead, Caputo’s emphasis is here more upon the “it” in operation as it “spooks” thought, being, and God. Again, much of the groundless ground covered in these particular investigations is also familiar, yet now revolving around the “It” as signifying descriptor.

The practical consummation toward which Caputo takes his readers with all this talk of spooking is in placing the burden of the unheard call back upon his readers, a move he has made of late in other recent works perhaps to address the matter of the political. With this end in mind, we can identify that the call’s job remains to “spook”, which is built upon the dual ghosts of the past (the dangerous memory) and the future (the absolute/unforeseeable) that are both within the present moment of decision making confronting all readers.

Caputo thereby reaffirms that such moments are resistant to hypostatizing. In this disrupted and wavering present, the answering to the call is left to the open-endedness of the absolute future where guarantees are not given regarding what is coming, monsters or messiah. It is safe to assume that Caputo is still committed to the convictions of his earlier writings. We might add that this open-endedness is addressed specifically to the “poor existing individual,” contra the systematic individual of political modernism bent on strong ideological solutions although such themes are not here explicitly examined.

Caputo is here once again advocating for a spooky reading of the theological/atheistic question by challenging his readers with the claim that God does not exist, but does insist. In calling forth God’s import of insisting contra existing, Caputo wants to preserve from the name of God the dangerous memory that calls forth deconstruction’s messiah, who will never come but will always be close-at-hand, in order to prod neoliberalism to further realizing the democracy-to-come that will never arrive definitively.

The vast majority of other contributions to the text sing in unison the praises of Caputo’s weak/spectral theology of the unheard call. As suggested at the outset, there is a mixture of different genres or media, such as essays, letters, poems, paintings photos, and floating or spiraling text.

In review of the artwork of the text, it is probably most apt to follow Derrida’s own lead, from an incident in Zeitgeist Fil m’s 2002 documentary Derrida, where Derrida himself views a portrait done of him by an artist, and simply responds, “I accept.” Based on the parameters of expectation for a scholarly book review, I would merely say they are enjoyable to behold and more or less foreign to Caputo’s traditional theoretical canon.

m’s 2002 documentary Derrida, where Derrida himself views a portrait done of him by an artist, and simply responds, “I accept.” Based on the parameters of expectation for a scholarly book review, I would merely say they are enjoyable to behold and more or less foreign to Caputo’s traditional theoretical canon.

With artwork scattered throughout the text, there is likewise interwoven a substantial amount of more common scholarly intellectual callings proffered in the textual essays. As with the artwork, the essay tend to promote or coincide with Caputo’s hermeneutics. For example, in his essay “Spectral Technologies: Turning Poltergeists Into Holy Ghosts”, Peter Rollins focuses on spooking things up for political systems and even his own parameters of belief. To accomplish “real transformation”

Rollins identifies that for systems outsiders are often helpful when trying to locate what haunts us. (75) In the particular context of his practicing Lacanian/Christian-atheist group, Rollins relates how he tries to performatively usher in such a transformation. In specific, he references his group’s re-enactment of The Last Supper when they invite an outsider to critique him and his fellow adherents, asking, “What’s your critique of us?”(75)

In such a quasi-Habermasian invitation to open dialogue with its implicit assumption that all the world’s problems could be resolved if we could only understand each other through the other’s eyes, Rollins’s hope is that such hospitality will enable him to transcend his own limitations. In acknowledgment of his general concern for such limitations, Rollins warns, “we’re generally so immersed in a given ideology that we can’t even imagine a genuine alternative.” (75) The ultimate goal, when confronting power, is therefore achieved when we confront the system with the ghosts of shame and embarrassment.

In the essay “Ghosting Theology”, Clayton Crockett provides some interesting biographical information about the institutional, or relational, links between himself, Charles E. Winquist, Caputo, and Jeff Robbins. The more theoretically focused contribution of the essay materializes in Crockett’s second half of his essay when he questions the political possibilities of radical theology. Building off Robbins’s insight that in radical theology the political is marked by its absence, Crockett reasserts that “the explicit absence of political theorizing for radical and postmodern theology meant that it was unable to adequately address situations like the post-9/11 world.” (124) Comparatively, he adds, “radical theology continues to attest to this spectral possibility (the Kingdom), even if it lacks the strength to actualize it in the world.” (125)

Former pastor Brian D. McLaren’s contribution to the text is the essay Will It Preach? McLaren initially questions the selling power of a God that insists instead of exists. With this in mind, he commences by suggesting that the average churchgoer would not want to be spooked or haunted, but they would instead prefer “a genii with wish-granting power.” (132) In this way, McLaren approaches his subject matter with an eye to a homogenous construct of a “typical local church.” (132)

However, he later breaks with this line of thinking by questioning if the exception to the rule in such “a typical local church” is not itself more common than the rule itself. Based on his own pastoral experience, McLaren highlights how often he has been surprised by people writing to him to confess via their own questions about the rule. (133) Based on his experience with these exceptions as the rule, McLaren then wonders if such a call isn’t exactly what people really need in what he describes as “today’s strange moment.” (133) In such a call, McLaren is therefore in the end content to prescribe Caputo’s vision to faith communities.

In Kyle A. Roberts’ essay “From Haunting to Shaking”, we find a sympathetic onto-theological response that contra McLaren does not see in Caputo’s hauntology the revenant of a Moses-type figure to lead the faithful through the parted dangers of worldly injustice and human frailty. Without the onto-theological guarantee of the eschaton of a final judgment and coming of the metaphysical Kingdom, Roberts wonders what all the talk of haunting will amount to for the limited reach of human agents.

Roberts admits he could get on board with a call to end the injustice of the world in actual historical time, echoing the unacknowledged revenant of the specter of the unmentioned Christian Socialists, but he finally falls more in line with something akin to a conviction of Niebuhrean realism that does not envision such a thing emerging in history. Instead, Roberts wonders if a God who haunts is not inadequate to the task of providing meaningful hope; whereas, he thinks what is really needed in contrast is a God who shakes up the world, as opposed to merely haunting it.

of the unmentioned Christian Socialists, but he finally falls more in line with something akin to a conviction of Niebuhrean realism that does not envision such a thing emerging in history. Instead, Roberts wonders if a God who haunts is not inadequate to the task of providing meaningful hope; whereas, he thinks what is really needed in contrast is a God who shakes up the world, as opposed to merely haunting it.

Admittedly, in a spooky sense of the topic, there is something holier sounding about putting aside economic measurements and laying open hospitality to the unforeseeable future. However, as a finite mortal in a finite world, one wonders if the defenders of poor and oppressed might not be best served by turning their attention to the weights and measures outside the text?

In Caputo’s defense, this focus is the burden he leaves to the recipients of his call, yet it is not insignificant to mention that such a response need be, according to Caputo, the work of Kierkegaard’s “poor existing individual.” (29) In other words, Caputo has in mind such an agent of justice and progress that must act alone outside of, or at least never fully within, systems or parties.

Caputo, like Derrida, continues with good cause to be haunted by the specter of the “other “political systems of the twentieth century. He is advocating an ideal of a system-without-system in place of such dangerous systematic approaches and thereby paralleling in part Eric Voegelin’s concern for immanentizing the eschaton. Of course, Caputo is actually calling for such an immanentization, in part, at least temporarily.

It Spooks is a valuable example of Caputo’s contribution to the return to religion for continental philosophy.

Rob Kennedy received his PhD in Classics and Religious Studies in 2014 from the University of Ottawa. The title of his thesis was “Assessing the function of Irony in Continental Philosophy’s Return to Religion: After the Death of God (The Vattimo/Caputo Dialogue)”.