The following is the second installment of a three-part series. The first one can be found here. Translated by Philipp Schlögl.

Letters II: The Schematism of the Pure Concepts of the Understanding as Starting Point

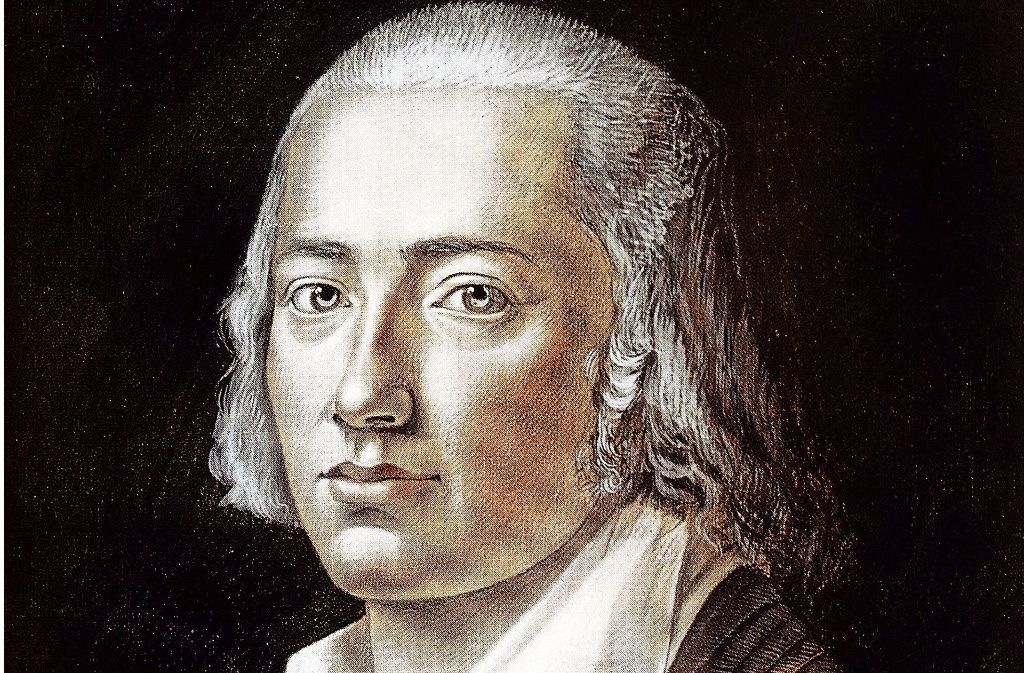

In a letter of January 26, 1795, addressed by Hölderlin from Jena to his friend Hegel, who was staying in Bern, he tells of, among other things, his experiences with Fichte’s lectures and his “curious” (merkwürdig in the sense of remarkable) interpretation of the Kantian antinomies:

His examination of the reciprocal determination of the I and the Not-I (in his language) is certainly curious; also the idea of striving etc. I must break off, and must ask you to regard all that as as good as not written. That you’re getting to grips with the concepts of religion is certainly good and important in many respects. The concept of providence I imagine you’re dealing with in exact parallel to Kant’s teleology; the way in which he connects the mechanism of nature (and so also of destiny) with its purposiveness really seems to me to contain the whole spirit of his system. Of course it is the way he solves all antinomies. In regard of the antinomies Fichte has a very curious thought, but I’d prefer to write to you about it on another occasion. For a long time now I’ve been thinking about the ideal education of the people, and because you are in the middle of dealing with a part of that, religion, perhaps I’ll choose your image and your friendship as the conductor of my thoughts into the outer world of the senses and write in good time what I would perhaps have written later in letters to you which you can judge and correct.[1]

1) This passage is a philosophically dense, but quite erratically articulated and full of unexecuted ideas. I want to point out only a few aspects briefly. In this letter the question of how to deal with the antinomic character of our access to the world plays a central role. Hölderlin considers this as a point at which Fichte remarkably goes beyond Kant. Fichte’s lectures are a key stimulus for Hölderlin’s search for a way out of Kantian thought, although he does not simply adopt Fichte’s concepts.[2] Hölderlin then sees “the whole spirit of his system” (the Kantian system; EaL 48) in teleology, i.e. the unification of the mechanism of nature and its expediency, which puts a particular emphasis on the second part of the Critique of Judgement. Moreover, Hegel’s reflections on religion are repeatedly incorporated into the text.

2) At the end of the passage, Hölderlin develops an image, perhaps nothing more than an association, of great significance. Hölderlin addresses himself to Hegel when he writes: “perhaps I’ll choose your image and your friendship as the conductor of my thoughts into the outer world of the senses”.[3] For Hölderlin, Hegel’s image and friendship take on the role of a mediation of thoughts with the outer world of the senses. It is precisely this task of mediation (synthesis), which points to the centre of Kantian philosophy and which Kant is concerned with in the Schematism of Pure Concepts of Understanding, namely “to show the possibility of applying pure concepts of the understanding to appearances in general”[4].

This requires a third party which is in a “similarity” both with the category (the pure concepts of understanding) and with appearance and which refers to time. Time does not precede the process of mediation but constitutes itself in it or rather as this process. The “transcendental schema”[5] plays the connecting role of the third. It is not a (timeless, externally applicable) tool and cannot be objectified, but “is rather only the pure synthesis”[6], activity and happening and thus neither active nor passive; it has a temporal, or rather time-forming, time-making, time-determining character.

Outside this temporal mediation, neither the categories nor the view is valid.[7] There is therefore no mediation of a reality that can be fixed for itself in thought (the categories) and an amorphous material of sensuality (the view) which are to connect subsequently. Only in their temporal, time-forming, time-determining relation to each other, only in the synthesis, do the two of them become extremes of the relation. There is no possibility to go back behind the character of the synthesis in order to either find existing objects or subjects in themselves or to find a fixed starting point for mediation. Kant calls the ability to form the schemata of pure concepts of understanding the productive power of imagination.[8]

3) Hölderlin takes up this concept associatively and puts Hegel’s image (note the proximity of schema and image) and friendship, i.e. everything he associates with his friend and his thinking, in the place of the time-forming synthesis, which connects the thoughts with the sensual world that otherwise would not exist outside this connection: “perhaps I’ll choose your image and your friendship as the conductor of my thoughts into the outer world of the senses” (EaL 48).

In this connection, however, Hölderlin and Kant pursue different interests. Kant has the critical interest to inquire how the world can be experienced as an object world at all[9], and then elaborates the schematizing activity of the mind (the time-forming synthesis) on the basis of the categories of quantity, quality, relation and modality previously derived from the functions of judgement.[10] Hölderlin’s question as to how any categories of thinking can be combined with the experience of the sensual sounds similar but is less epistemologically motivated than poetologically.

Here the transition begins that Hölderlin described a year later in his letter to Niethammer as the endeavour to “go on from philosophy to poetry and religion”. In Hölderlin’s work, the critical question adopted from Kant about the mediation of concepts of understanding and intuition will develop further into the question of how this mediation can find an expression in language. For Hölderlin this synthesis will only take place if it can also be communicated in a language (and that means for him especially in the form of poetry). Outside of language the synthesis has no existence, and its extremes, the categories of thinking and the outer world of the senses, disintegrate.

Possibility as Repetition of Reality: Being Judgment Possibility

1) One of Hölderlin’s first philosophical texts, Seyn, Urtheil, … (TS 7f/Being Judgment Possibility, EaL 231-232)[11], also shows that Hölderlin’s reception of Kant has an essential starting point in the chapter on Schematism, but that he also distances himself from the conception developed there.

The question posed in this text, which consists of three parts (being, judgment, the categories of modality), is similar to that posed in the aforementioned letters. At the beginning of the text Hölderlin defines the concept of being precisely through the connection between subject and object: “Being – expresses the connection of subject and object.” (EaL 231). He then connects the intellectual intuition with this “absolute being” (EaL 231).

Here, too, it is not a matter of theoretical knowledge or the determination of a primordial existence before all separations, but rather of the text itself disintegrating into the parts Seyn (unification) and Urtheil (separation) – considering the first two sections –, thus reflecting the inevitable division. Speaking of absolute being is not possible without speaking of separation. However, Hölderlin notes: “The concept of division itself contains the concept of a reciprocal relationship between object and subject, and the necessary premiss of a whole of which object and subject are the parts.” (EaL 231) This necessary precondition for thinking (here Hölderlin follows Kant’s criticism) must not be regarded as something given or as the object of knowledge.

The categories of modality (possibility, reality, necessity) can be regarded as a function of the union of union and separation, of the union of Seyn and Urtheil, which can no longer be objectified now.[12] The synthesis of subject and object (or of Seyn and the separate) is, as will be shown below, not determined by the categories of modality with regard to content, but as it regards its character. It shows itself as possible, real or necessary.

The three categories of modality do not enable the determination of the content which the subject attributes to the object associated with it in the synthesis, but rather focus the perspective on the space between the two poles in which they relate to one another. They introduce a form of distance, delay, deceleration into the union of subject and object that does not take place immediately, but under the perspectives of possibility, reality and necessity. These are, as it were, inseparable from the process of synthesis (or mitgängig[13]).

2) When Hölderlin refers to the three categories of modality in the last section of Being Judgment Possibility, he adopts them by the terms Kant uses in the chapter on Schematism: possibility, reality and necessity. In the first mention of the categories of modality when describing the table of categories, however, Kant speaks of possibility, existence (Dasein) and necessity.[14]

It is important that Kant distinguishes the categories of modality from the categories of quantity, quality and relation, which becomes clear in the specific manner of the temporal synthesis of categories of understanding and phenomena that the process of schematization is about. Synthesis as a form of becoming temporal of the I think (Ich denke) has, in relation to modality, the character of the concept of time, i.e. the way in which time correlates with the determination of an object: Possibility means the notion of an object at any arbitrary time, reality means its existence at a certain point in time, and necessity means its existence at all times. Thus, the schemes of modality open up the possibility to relate the possible objects to time; as already indicated, this does not contribute anything to the determination of the object itself:

The principles of modality are not, however, objective-synthetic, since the predicates of possibility, actuality, and necessity do not in the least augment the concept of which they are asserted in such a way as to add something to the representation of the object.[15]

The categories of modality do not refer to an objective, i.e. object related, but the subjective-synthetic relation, which (mediated by the respective way of correlation between the determination of the object and time) indicates the corresponding “cognitive faculty” in the subject[16]: “The principles of modality therefore do not assert of a concept anything other than the action of the cognitive faculty through which it is generated.”[17] Hölderlin summarizes this recapitulatory statement from the end of the chapter on Die Postulate des empirischen Denkens überhaupt in a concise, perhaps somewhat simplistic form, when at the end of Being Judgment Possibility he states that the concept of necessity applies “to the objects of reason” – and further: “The concept of possibility applies to the objects of the understanding, that of reality to the objects of perception and observation.” (EaL 232)[18]

3) Two points are relevant here. First, Hölderlin gives the category of possibility a peculiar drift in Being Judgment Possibility; second, there is a way which leads from here to the Critique of Judgment, the significance of which for Hölderlin has already been pointed out.

First, in Being Judgment Possibility there is a decisive passage which makes a new accentuation: “If I think of an object as possible, then I am only repeating the prior consciousness by force of which it is real. There is for us no conceivable possibility that would not be a reality.” (EaL 231-232) The three categories of possibility, reality and necessity do not stand side by side on the same level and do not only refer to different ways in which time and determination of the object correlate, but possibility and reality are put into a direct relation.

However, they do not function in such a way that possibility becomes reality (is realized), but vice versa. What is possible refers to a reality that precedes it and that is being repeated. Hölderlin thus sets himself apart from a powerful tradition of philosophical thought that focuses on transforming the ambiguity of the space of possibility into the unambiguity of reality; dýnamis is completed in enérgeia.

Reality and possibility neither stand side by side without connection, nor are they related to each other in the mode of fulfilment (of possibility through reality), but are constituted around the distance, the difference, the displacement that occurs with repetition.

Second, Repetition – understood in Hölderlin’s sense – opens reality up to a space of possibility that eludes any immediate conceptual definition. Starting from here, Hölderlin can take the transition to the aesthetic ideas, as Kant determines them in the Critique of Judgment. In this, the concept of repetition (“then I am only repeating the prior consciousness”, EaL 232) is decisive.[19]

In the first paragraph of the Critique of Judgment, Kant distinguishes the judgment of taste from the judgment of cognition. The judgment of taste, which indicates whether something is beautiful, does not refer to an idea of the object in order to determine it more accurately, but refers the idea to the “subject [which] feels himself, [namely] how he is affected by the presentation”.[20] What the categories of modality and the judgments of taste have in common is that they do not convey any knowledge about the object, but rather open up the space of the subject’s respective relationship to the notion of an object – be it with regard to the subject’s corresponding cognitive faculty (modality), be it in its affection by the imagination (judgment of taste) – as a moment that is accompanying (mitgängig) the cognitive process, the process of the constitution of the object.

Special attention should be paid to the turn of phrase that in the judgments of taste, the subject, affected by the imagination, feels itself. As in the representation of the inner sense, i.e. of time, in the Critique of Pure Reason, a hiatus, a difference, a distance, which cannot be closed by conceptual knowledge (logical judgments), is also shown here through the affection in the subject. Hölderlin also sees this difference in the transition from reality to possibility. The repetition corresponds to this distance, this difference, this displacement. According to Hölderlin, poetry (art) and religion, which (as shown below) are conceived on the basis of repetition, are symbolizations or forms of dealing with and shaping this opening moment.[21]

4) In need of clarification is what Hölderlin’s strange determination of the category of possibility is all about as a repetition of what really is. In my view the key to this lies in paragraph 49 of the Critique of Judgment, in which Kant unfolds the meaning of aesthetic ideas: “by an aesthetic idea I mean a presentation of the imagination which prompts much thought, but to which no determinate thought whatsoever, i.e., no [determinate] concept can be adequate, so that no language can express it completely and allow us to grasp it”.[22] And a little later he adds as an explanation: “For the imagination (in its role as a productive cognitive power) is very mighty when it creates, as it were, another nature out of the material that actual nature gives it.”[23] The productive power of imagination, which has already been present in the chapter on schematism and which, in Kant’s case, in a certain way represents the heart of the process of cognition (because it allows the categories to be applied to perception), is thus not merely a tool, but “creative”[24].

It is not exhausted in its logical function, which serves the acquisition of knowledge (the determination of the object).[25] The power of imagination has an anarchic moment in itself which cannot be grasped in a certain concept and which does not (directly) contribute anything to the (scientific, logical) knowledge of an object, but which accompanies the process of application of the categories of understanding to perception, and therefore does not merely originate from imagination.

The power of imagination is “very mighty when it creates, as it were, another nature out of the material that actual nature gives it.”[26] Thus the point is reached which is decisive for Hölderlin. He interprets this capacity of imagination (the creation of another nature from the material that the real one gives to it) as a repetition of the real nature. This corresponds to his definition of the category of possibility: “If I think of an object as possible, then I am only repeating the prior consciousness by force of which it is real.” (EaL 231)[27]

Jakob Helmut Deibl is a post-doctoral fellow at the Department of Systematic Theology in the special field of Fundamental Theology at the Faculty of Catholic Theology at the University of Vienna. His dissertation examined Gianna Vattimo’s suggestion of a transformation of the biblical motives of incarnation and kenosis (the incarnation and the relinquishment of the Divine Logos) with regard to a reinterpretation of Europe emphasizing the motive of the weakening of strong structures and noetic claims of absoluteness.

________________________________________________________________________

[1] Brief 94, 26. Jänner 1795, MA II, 567-569, here: 569/EaL 47-49, here: 48 seq.

[2] Hölderlin’s letter to Hegel, which unfortunately has not been completely preserved, also indicates a critique of Fichte’s system, which Hölderlin might also have told Fichte, whose lectures he enthusiastically listened to. Unfortunately the letter has a gap at the place where it says “Fichte confirms my” (Brief 94, January 26, 1795, MA II, 567-569, here: 569/EaL 47-49, here: 48). On Hölderlin’s reception of Fichte cf. Violetta Waibel, Hölderlins Rezeption von Fichtes „Grundlage des Naturrechts“, in: HJb 1996/97, 146-172.

[3] Brief 94, 26. Jänner 1795, MA II, 567-569, here: 569/EaL 47-49, here, 48 seq.

[4] Kant, KrV B 177/Kant, CPR, 272. In his second letter to Böhlendorff Hölderlin refers to a similar structure when he writes about the “phenomenalization of concepts” (Brief 240, November 1802, MA II 920-922, here: 921/EaL 247-249, here: 248).

[5] Kant, KrV B 177/Kant, CPR, 272.

[6] Kant, KrV B 181/ Kant, CPR, 274.

[7] Cf. Appel, Zeit und Gott, 73-76.

[8] The “schema of a pure concept of the understanding, […] is a transcendental product of the imagination, which concerns the determination of the inner sense in general, in accordance with conditions of its form (time) in regard to all representations, […].” (Kant, KrV B 181/Kant, CPR, 274).

[9] Cf. Appel, Zeit und Gott, 76.

[10] Cf. Kant, KrV B 105f; 181-187/Kant, CPR, 211f.; 273-277.

[11] Cf. Michael Franz, Hölderlins Logik. Zum Grundriß von ‚Seyn Urtheil Möglichkeit‘, in: HJb 1986/87, 93-124; here especially: 118-123; Michael Franz., Einige Editorische Probleme von Hölderlins theoretischen Schriften. Zur Textkritik von ‚Seyn, Urtheil, Modalität‘, ‚Über den Begriff der Straffe‘ und ‚Fragment philosophischer Briefe‘, in: HJb 2000/01, 330-344, here: 330-333; Michael Franz, Theoretische Schriften, in: Hölderlin Handbuch, 224-246, here: 228-232; Kreuzer, TS XIII-XV and 119.

[12] Cf. The beautiful formulation by Michael Franz: “Under the condition of (the) ‘Ur-Teilung’ (primal-separation), the categories of modality constitute a relationship between the separated parts – subject and object.” (vgl. Franz, Theoretische Schriften, in: Hölderlin Handbuch, 224-246, here: 232 [Translation: Sara Walker]).

[13] I adopt this term from Dieter Mersch.

[14] Cf. Kant, KrV B 105f; 184/Kant, CPR, 211f.; 275.

[15] Kant, KrV B 286; cf. B 74 and B 286f/Kant, CPR, 332; cf. 193 and 332f.

[16] Thus, although nothing is added to the determination of the objects, the categories of modality do not merely lead to analytical judgments that must merely correspond to the principle of freedom from contradiction, but to synthetic judgments relating to possible experience, i.e. „to go beyond a given concept“. (Kant, KrV B 194/ Kant, CPR, 281).

[17] Kant, KrV B 287/Kant, CPR, 333.

[18] Cf. Franz, Theoretische Schriften, in: Hölderlin Handbuch, 224-246, here: 232. A detailed description of the postulates of empirical thinking can be found in Giuseppe MOTTA, Die Postulate des empirischen Denkens überhaupt. KrV A 218-235 / B 265-287. Ein kritischer Kommentar (Kantstudien Ergänzungshefte 170), Berlin / Bosten 2012.

[19] Hölderlin talks about his own version of aesthetic ideas in a letter to Neuffer dated 10 October 1794: “Perhaps I’ll be able to send you an essay on aesthetic ideas; […] In essence it is to contain an analysis of the beautiful and the sublime in which the Kantian analysis will be simplified and also, from another perspective, varied and extended, as Schiller has already done in part in his treatise on ‘Grace and Dignity’, though he has ventured a step less beyond the Kantian borderline than he should have done in my opinion.” (Brief 88, 10. Oktober 1794, MA II, 548-551, here: 550f/EaL 31-35, here: 34) On the significance of the term aesthetic ideas for Hölderlin cf. Violetta Waibel, “Wenn der Dichter einmal des Geistes mächtig …”. „Leben. Geist. Bewegung. Thätigkeit“. Anmerkungen zum Geistbegriff der Dichterphilosophen Hölderlin und Hardenberg, will be published in 2019.

[20] Kant, Kritik der Urteilskraft, Werkausgabe Band X, hrsg. von Wilhelm Weischedel, Frankfurt am Main 212014 [below KdU] § 1, 115/Kant, Critique of Judgement, translated, with an introduction, by Werner S. Pluhar, with a foreword by Mary J. Gregor, Indianapolis/Cambridge 1987, 44. The judgment on taste does not state that the object x is objectively beautiful and that this determination is part of its characterisation.

[21] I owe this consideration to Kurt Appel.

[22] Kant, KdU § 49, 249f/Kant, Critique of Judgement, 182.

[23] Kant, KdU § 49, 250/Kant, Critique of Judgement, 182.

[24] Kant, KdU § 49, 251/Kant, Critique of Judgement, 183.

[25] “When the imagination is used for cognition, then it is under the constraint of the understanding and is subject to the restriction of adequacy to the understanding’s concept. But when the aim is aesthetic, then the imagination is free, so that, over and above that harmony with the concept, it may supply, in an unstudied way, a wealth of undeveloped material for the understanding which the latter disregarded in its concept. But the understanding employs this material not so much objectively, for cognition, as subjectively, namely. to quicken the cognitive powers, though indirectly this does serve cognition too.” (Kant, KdU § 49, 253/Kant, Critique of Judgement, 185.)

[26] Kant, KdU § 49, 250/Kant, Critique of Judgement, 182.

[27] The category of possibility is therefore of decisive importance. Dieter Henrich, however, has a different view on the unusual classification of the categories of modality in Being Judgement Possibility: “It [classification] seems to aim at minimalizing the role of the concept of possibility” (Dieter Henrich, Der Grund im Bewußtsein. Untersuchungen zu Hölderlins Denken (1794-1795), 709, cf. also 715 [Translation: Sara Walker]).