The following is the first installment of a three-part series. Translated by Philipp Schlögl.

Introductory Remarks

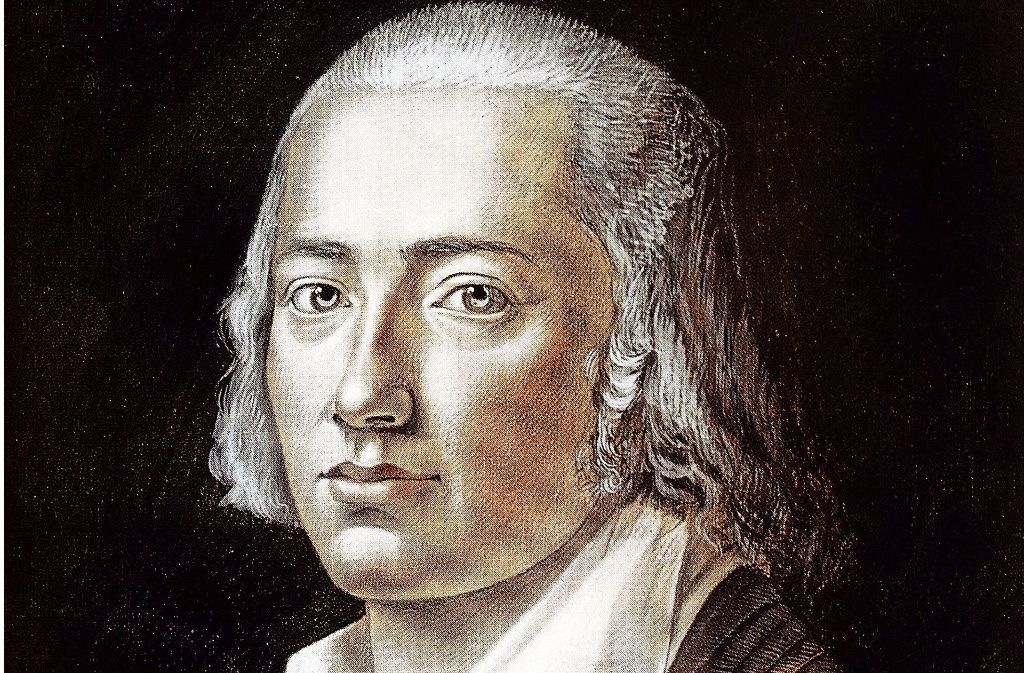

Friederich Hölderlin’s famous quote “Thus all Religion would be poetic in its essence.” (EaL 239)[1], which is taken from the Fragments of Philosophical Letters (1796/97, EaL 234-239)[2], does not represent a mere rapturous exclamation of the poet who wants to dissolve religion into poetry. It condenses Hölderlin’s intensive philosophical examination of Kant’s writings and Fichte’s lectures, which can be found in his letters and conversations with Immanuel Niethammer, Schiller, Schelling, Fichte, Hegel and others.[3] This sentence summarizes a development that is still of the greatest relevance today for determining the relationship between philosophy, theology and aesthetics.

In the following article I will trace where the important pivots of Hölderlin’s peculiar reception of Kant are and what drift he gives to Kant’s conception. In contrast to an interest primarily critical of knowledge (Kant), Hölderlin attempts to determine the place of poetry and religion in the architectonics of thought. Poetry and religion prove to be related to each other and are closely related to the categories of modality, especially that of possibility, as well as to the space opened up by aesthetic ideas in Kant’s Critique of Judgment. Hölderlin’s central categories are the sphere as a cipher for an intersubjective, linguistically, historically and culturally mediated interaction with the world, which replaces the dichotomy between subject and object, and the repetition as the opening of a utopian space of possibility.

Letters I: “… in them I will go on from philosophy to poetry and religion”

1) When Hölderlin wrote from Jena to his brother Carl on 13 April 1795, he gave an excellent brief introduction to the significance of the moral law and the postulates of practical reason in Kant’s work and developed them further towards Fichte’s basic idea of the I and the non-I. Of central importance here is the motif of infinite progress. On “coming nearer to his aim of the greatest possible moral perfection”[4] he writes:

But since this aim is impossible in this world, and since it cannot be attained within time and we can only approach it in infinite progression, we have need of a belief in an infinite extent of time because the infinite progress in good is an uncontestable requirement of our law. But this infinite extent of time is inconceivable without faith in a Lord of nature whose will is the same as the command of the moral law within us, and who must therefore want us to endure infinitely because he wants us to make infinite progress in good and, as the Lord of nature, also has the power to realize that which he wants. [5]

Here Hölderlin is still within the realm of practical philosophy, the matter of aesthetics is not mentioned in the entire letter. About half a year later, in a letter to Schiller dated September 4, 1795, the unification of subject and object appears as the decisive question that every philosophical system must ask itself, alongside the motif of infinite progress[6]:

I am attempting to work out for myself the idea of an infinite progress in philosophy by showing that the unremitting demand that must be made of any system, the union of subject and object in an absolute… I or whatever one wants to call it, though possible aesthetically, in an act of intellectual intuition, is theoretically possible only through endless approximation, like the approximation of a square to a circle; and that in order to arrive at a system of thought immortality is just as necessary as it is for a system of action. [7]

In these sentences a program for a philosophy to be developed is presented (“I am attempting to work out for myself […] by showing […]”), whereas in the letter to his brother Hölderlin initially only summarizes the philosophical systems of Kant and Fichte that were formative to him. At the center of the short passage, as mentioned above, there are two images, one of infinite progress or infinite rapprochement and the other of the unification of subject and object.

First, the image of infinite progress recalls the central question in Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason as to how reason deals with the inevitably occurring figures of an infinite progressus, that are in danger of being understood as an inadmissible extension of our knowledge of objects (Kant talks about “transcendental illusion”/“transzendentalen Scheine”[8]). The idea that the immortality of the soul must be regarded as necessary not only for action (with practical intent), but also for the realization of a system of thought, is connected to this very figure of infinite expansion, namely the ego or the soul. It would be worth discussing to what extent Hölderlin differs from, or continues, Kant’s thinking in this. This discussion must be omitted here.[9]

To show that every philosophical system must be concerned with the unification of subject and object in the absolute cannot mean that subject and object are directly related to one another. This would undermine the entire Kantian epistemology, which is initially devoted to the question of how potential objects of experience are constituted at all. It would make the entire intermediate space disappear, which is located between the categories of the subject’s intellect and the data of perception and which is highlighted by Kant in the Schematism of the Pure Concepts of Understanding (Schematismus der reinen Verstandesbegriffe). However, it is precisely this interspace that is of central importance for Hölderlin’s reception of Kant, as will be shown below.

In his letter to Schiller, Hölderlin does not really name the point of unification in the absolute, but merely indicates it with a placeholder (absolute ego – “or whatever one wants to call it”), rather pointing towards a function. It becomes clear that it is not his intention to positivize something unconditional that lies before all separations – nor is it a matter of positivizing two given poles, the subject and the object, which would be related to this absolute. Rather, Hölderlin is concerned with the movement of overcoming otherwise disparate aspects of reality, which he addresses with the ciphers subject and object.

He thus takes up perhaps the most fundamental dichotomy of modern philosophy (in a later letter, which will be discussed below, he enumerates further dichotomies) and suggests that overcoming the dichotomous character of the concept of reality must be the task of philosophy. The unification has an aesthetic character and is called intellectual intuition (intellectuale Anschauung). It is not conceived in terms of infinite rapprochement which decisively shapes this passage.

2) The motifs mentioned can be explained more precisely through a letter Hölderlin sent to the philosopher Immanuel Niethammer half a year later in February 1796.

In the philosophical letters I want to find the principle that will explain to my satisfaction the divisions in which we think and exist, but which is also capable of making the conflict disappear, the conflict between the subject and the object, between our selves and the world, and between reason and revelation, – theoretically, through intellectual intuition, without our practical reason having to intervene. To do this we need an aesthetic sense, and I shall call my philosophical letters New Letters on the Aesthetic Education of Man. And in them I will go on from philosophy to poetry and religion.[10]

Again, the letter contains a reference to Hölderlin’s project. In echo of Schiller’s Letters on the Aesthetic Education of Man, Hölderlin wants to write New Letters on the Aesthetic Education of Man. He names the transition from philosophy to poetry and religion as an essential content. This transition is connected with the search for a way of dealing with the divisions with which modern philosophy operates right up to Kant. While Hölderlin had only mentioned the separation of subject and object in his letter to Schiller, he now adds the “conflict” between self and world, as well as between reason and revelation. Obviously, it is not only about the modern subject/object constellation, but about a modern development in which thinking – in various respects – falls apart in forms of a no longer mediable conflict.

For Hölderlin it is clear that there is no way (back) to a tensionless primordial unity that precedes the divisions. At first the divisions in which our thinking is caught have to be understood, i.e. understanding one’s own time: “to find the principle that will explain to my satisfaction the divisions in which we think and exist”.

Moreover, Hölderlin is also concerned with preventing the disintegration of thought into two completely separate areas that can no longer be mediated. When Hölderlin speaks of a “principle”, he does not mean an unconditional principle of unity (a metaphysical principle of being) that could be objectively conceived. In this principle, reason, expressed in Kant’s terminology, would fall prey to the transcendental appearance (transzendentaler Schein) that arises when one considers the conditions of thought in the subject to be something positively given.[11]

The principle mentioned must therefore be found in a form of thinking, a function, a process; unlike Kant, however, Hölderlin does not (primarily) think of practical reason as the pivotal point of the mediation of the dichotomies and antinomies that constantly break open anew in thinking. He strives to understand and explain them from the point of view of theoretical knowledge, again mentioning the motif of intellectual intuition. In my opinion, at first this motif is rather a kind of cipher for an aspect beyond the dichotomies, which is nevertheless not to be found in practical philosophy, but has to do with intuition. What is the point of naming this motif at the point of transition from philosophy to poetry and religion?

3) In his Critique of Pure Reason, at the end of Transcendental Aesthetics, Kant emphasizes that the intellectual intuition can only be had by an “original being”, but not by man as “one that is dependent as regards both its existence and its intuition”[12]. For Kant it would mean a form of immediate self-knowledge that would skip the temporally structuring synthesis as which the ego (the “consciousness of itself”[13]) evolves:

If the faculty for becoming conscious of oneself is to seek out (apprehend) that which lies in the mind, it must affect the latter, and it can only produce an intuition of itself in such a way, whose form, however, which antecedently grounds it in the mind, determines the way in which the manifold is together in the mind in the representation of time[14].

The ego does not intuit itself “as it would immediately self-actively represent itself, but in accordance with the way in which it is affected from within”[15]. The “self-intuition of the mind”[16] (“Selbstanschauung des Gemüts”) is thus characterized by a process of affection and becoming affected[17] – two processes that do not coincide completely (otherwise the inner intuition would be intellectual). This hiatus, which cannot be closed, is time or emerges as time. Kurt Appel expresses this as follows:

There is an unbridgeable gap between the act of setting and the representation of it, which is why the idea is not only the active moment of affecting, but also an act of being affected. Time is precisely this moment between activity and passivity, this difference that spreads in the act of each self-affection.[18]

In the subject, more precisely in the synthesizing act that determines the subject, there remains a non-closing moment of displacement, of difference. What remains is a gap which can no longer be traced back to a preceding starting point and which cannot be overcome by the subject through reflection.[19]

Hölderlin does not go back behind this insight either[20], but – as will be shown later – he will determine this difference as one of discretion and continuity. The recourse to the intellectual intuition in Niethammer’s letter does not want to encompass or abolish this difference, but refers, as Johann Kreuzer points out, to the fact that the forms of antagonism, of separation, of difference must be thematization in the aesthetic experience:

“Intellectual intuition” is a necessary prerequisite for the reflection on the structure of self-consciousness as well as for the explanation of the opposites that we discover as self-consciousness or rather that we find within self-consciousness. Intellectual intuition is neither something positive and factual nor is it something that can be theoretically determined. Concerning this, Hölderlin abides by Kant’s criterion. What is regarded as intellectual intuition, is the reality of an aesthetic experience. There is no object of intellectual intuition. (TS XV)[21]

The way in which aesthetic experience can symbolize and express this difference and this hiatus without retracing them to a preceding motif and thus dissolving them, but also how the tension in them can be balanced without turning their reconciliation into an infinite progress, is to be concretized in the fifth section of this text. Thereby the considerations “will go on from philosophy to poetry and religion”[22].

4) When Hölderlin juxtaposes the terms “theoretical” and “in intellectual intuition”, a direction is indicated that ranges from the theoretical evidence of the possibility of objective world experience (theoretical knowledge) to aesthetic experience, in Kant’s words from the Critique of Pure Reason to the aesthetic judgment: “To do this we need an aesthetic sense”[23], Hölderlin states. In order to trace the path taken by Hölderlin, the first question to be asked is where Hölderlin takes his starting point in the Critique of Pure Reason and how he moves towards the Critique of Judgment. The next section seeks to determine one of the essential points at which Hölderlin’s reception of Kant begins and from which he also begins to distance himself from Kant.

Jakob Helmut Deibl is a post-doctoral fellow at the Department of Systematic Theology in the special field of Fundamental Theology at the Faculty of Catholic Theology at the University of Vienna. His dissertation examined Gianna Vattimo’s suggestion of a transformation of the biblical motives of incarnation and kenosis (the incarnation and the relinquishment of the Divine Logos) with regard to a reinterpretation of Europe emphasizing the motive of the weakening of strong structures and noetic claims of absoluteness.

_______________________________________________________________________

[1] J. Ch. F. Hölderlin, Theoretische Schriften, ed. by Johann Kreuzer, Hamburg, 1998 [below TS], 15; Friedrich Hölderlin, Essays and Letters ed. and translated with an Introduction by Jeremy Adler and Charlie Louth, London 2009 [below EaL].

[2] TS 10-15; Cf. Friedrich Hölderlin, Sämtliche Werke, Stuttgarter Hölderlin-Ausgabe in acht Bänden, ed. by Friedrich Beissner, Stuttgart 1946-1985 [below StA], StA 4.1, 275-279, 416f and StA 4.2, 786-793; cf. Friedrich Hölderlin, Sämtlicher Werke und Briefe, Münchener Ausgabe, ed. by Michael Knaupp, Darmstatt 1998 [below MA], MA III, 387-389. For a reconstruction of the text cf. Michael Franz., Einige Editorische Probleme von Hölderlins theoretischen Schriften. Zur Textkritik von ‚Seyn, Urtheil, Modalität’, ‚Über den Begriff der Straffe’ und ‚Fragment philosophischer Briefe’, in: HJb 2000/01, 330-344, here: 335-344. An interpretation of the text is given by Kreuzer, cf. TS XV-XVIII and 120f; id., Zeit, Sprache, Erinnerung: Die Zeitlogik der Dichtung, in: ders (Hg.), Hölderlin-Handbuch. Leben – Werk – Wirkung, Stuttgart 2002/2011, 147-161; Michael Franz, Theoretische Schriften, in: Johann Kreuzer (Hg.), Hölderlin-Handbuch, 224-246, here: 232-236; Paul Böckmann, Hölderlin und seine Götter, München 1935, 203-210; Ulrich Gaier, „So wäre alle Religion ihrem Wesen nach poetisch.“ Säkularisierung der Religion und Sakralisierung der Poesie bei Herder und Hölderlin, in: Silvio Vietta/Herbert Uerlings (Hg.) Ästhetik – Religion – Säkularisierung I. Von der Renaissance zur Romantik, München 2008, 75-92, especially: 83-85; 91f; Charlie Louth, „jene zarten Verhältnisse“. Überlegungen zu Hölderlins Aufsatzbruchstück Über Religion / Fragment philosophischer Briefe, in: HJB 39 (2014/15), 124-138.

[3] Cf. Dieter Henrich, Der Grund im Bewusstsein; Christoph Jamme, „Ein ungelehrtes Buch“. Die philosophische Gemeinschaft zwischen Hölderlin und Hegel in Frankfurt 1797-1800 (Hegel-Studien, Beiheft 23), Bonn 1983; Violetta Waibel, Wechselbestimmung. Zum Verhältnis von Hölderlin, Schiller und Fichte in Jena, in: Schrader (Hg.), Fichte und die Romantik, 43-69.

[4] Brief 97, 13. April 1795, MA II 576-579, here: 577; vgl. MA III, 481-482; StA 6.2, 731-735/EaL 48-52, here: 49.

[5] Brief 97, 13. April 1795, MA II 576-579, here: 577f/EaL 48-52, here: 50.

[6] I doubt whether one should speak of the emergence of a “philosophy of unification” in view of this new central question about the unification of subject and object, as Christoph Jamme does in his outstanding study on Hegel and Hölderlin (cf. Jamme, “Ein ungelehrtes Buch”, 71-98). Already at this time Hölderlin has, as can be seen in Being Judgement Possibility, a strong awareness of the meaning of difference which cannot be abandoned.

[7] Brief 104, 4. September 1795, MA II, 595f/EaL 61-63, here: 62.

[8] Immanuel Kant, Kritik der reinen Vernunft, ed. by Jens Timmerman, Hamburg 1998 [below KrV], KrV, B 352/Immanuel Kant, Critique of Pure Reason, translated and edited by Paul Guyer and Allen W. Wood, Cambridge 1998, 385 [below CPR].

[9] Cf. for example the statement about the three cardinal theorems about the freedom of the will, the immortality of the soul and the existence of God: “If, then, these three cardinal propositions are not at all necessary for our knowing, and yet are insistently recommended to us by our reason, their importance must really concern only the practical.” (Kant, KrV, B 827f/Kant, CPR, 674)

[10] Brief 117, 24. Februar 1796, MA II, 614f, here: 615; vgl. StA 6.2, 783-787/EaL 66-68, here: 67.

[11] Cf. Hans Michael Baumgartner, Kants „Kritik der reinen Vernunft“. Anleitung zur Lektüre, Freiburg/München 21988, 101-104.

[12] Kant, KrV, B 72/Kant, CPR, 192.

[13] Kant, KrV, B 68/Kant, CPR, 189.

[14] Kant, KrV, B 68f/Kant, CPR, 189f.

[15] Kant, KrV, B 69/Kant, CPR, 190.

[16] Kant, KrV, B 69/Kant, CPR, 190.

[17] Kant writes about „the form of intuition, which, since it does not represent anything except insofar as something is posited in the mind, can be nothing other than the way in which the mind is affected by its own activity, namely this positing of its representation, thus the way it is affected through itself, i.e., it is an inner sense as far as regards its form“ (Kant, KrV B 67f/Kant, CPR, 189).

[18] Kurt Appel, Vom Preis des Gebetes, in: ID., Preis der Sterblichkeit. Christentum und neuer Humanismus (QD 271), Freiburg 2015, 186-228, here: 209 [Translation: Philipp Schlögl].

[19] Cf. Appel, Vom Preis des Gebetes, 208-210.

[20] This applies to Hegel in the same way (cf.. Appel, Vom Preis des Gebetes, 210f).

[21] Translation: Sara Walker.

[22] EaL 66-68, here: 67

[23] Brief 117, 24. Februar 1796, MA II, 614f, here: 615. On the significance of Kantian aesthetics for Hölderlin cf. the note to Hegel in the letter of 10 July 1794.: “My preoccupations are pretty focused at the moment. Kant and the Greeks are virtually all I read. I am trying to become particularly familiar with the aesthetic part of the critical philosophy.” (Brief 84, 10. Juli 1794, MA II 540f, here: 541/EaL 27-29, here: 29)