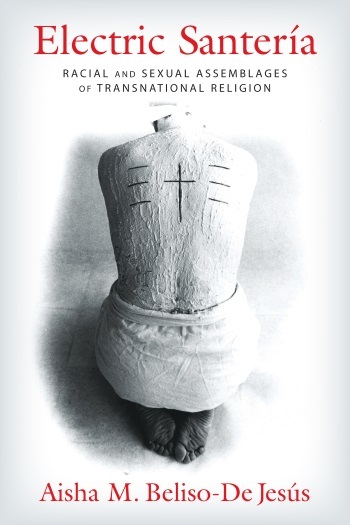

Mark I. Wallace. When God Was a Bird: Christianity, Animism, and the Re-Enchantment of the World. New York: Fordham University Press, 2019. 240 pages. ISBN-10: 0823281310.

A simple two-bedroom house sits along a busy street in a suburban neighborhood in the Midwest during the warmer months. Across the street there is a line of non-descript utility poles and upon the wires sit approximately 20 rock pigeons. As I sit and watch them, I find myself asking questions of a paradoxically mundane yet strange quality.

Why have they chosen that particular utility pole? Where do they go in the afternoon? Do they somehow comment on the cars passing by? Why do they sing? Do they laugh? Do they cry? Do they pray? Do they hope?

Are They God?

Many, especially those living and/or working within an intentionally Christian theological framework may be troubled by the last question. Does not the mere speculation of “avian divinity” violate the acceptable borders of biblical teaching and orthodox belief? How can one speak of “divine incarnation” as occurring in anything but “human flesh”? Is it not enough to simply call the bird a “creature of God”? According to Mark Wallace, it is not, and the refusal to “recognize the reality of God in creaturely manifestation” reveals the extent to which anti-ecological and anthropocentric ideologies have distorted the heart of Christianity.[1]

As our everyday lives become marked by the seemingly irrevocable consequences of global warming – erratic weather patterns and devastating natural disasters, species extinction and biodiversity loss – it is tempting to echo Lynn White, Jr.’s contention that “Christianity made it possible to exploit nature in a mood of indifference to the feelings of natural objects.”[2]

In his now famous article “The Historical Roots of Our Ecologic Crisis”, White points to the impact that the Christian story of creation has had on the development of exploitative technology and environmental degradation: “Man named all the animals, thus establishing his dominance over them. God planned all of this explicitly for man’s benefit and rule…And, although man’s body is made of clay, he is not simply part of nature: he is made in God’s images…Modern technology is at least partly to be explained as an Occidental, voluntarist realization of the Christian dogma of man’s transcendence of, and rightful mastery over, nature.”[3] And while White acknowledges Saint Francis as a radical alternative to the “monarchical” position of humanity within the Christian narrative, he frames Franciscan humility and pan-psychism as a deviation from or subversion of Christian theology.[4]

To a certain extent, Wallace does not disagree with this assessment, noting that Christianity is disproportionately responsible for cultivating an “otherworldly” detachment and denial of our and the world’s material, fleshy embodiment.[5] However, whereas White insists on the inherent anti-environmentalism of the Christian narrative, Wallace contends that the former’s

setup of the triumph of Christianity over animism is inattentive to historical complexity and contemporary nuance…while the axe-wielding saint is a powerful and disturbing image in Christian history, this trope only tells one side of the story….Christianity did not annihilate animism in its putative dualistic theology but rather sublated it to its articulation of the one God now enfleshed within this world through the human person of Jesus.[6]

Over the span of five chapters, Wallace articulates an alternative reading of the biblical text and Christian theology, arguing that the presumed anthropocentrism of both is in reality a distortion that has caused us to forget the “the core grammar” of Christianity’s “carnal-minded, fleshly, earthy, animalistic system of belief.”[7] Drawing on recent developments in Continental philosophy, specifically the fields of posthumanism and new materialism, Wallace presents Christianity as “animotheistic” and “animocentric”, wherein the movement of divine incarnation is a “promiscuous” embodiment throughout creation.[8]

In significant ways, When God Was a Bird expands and particularizes the shift within Christian theology toward an interdisciplinary methodology focused on uncovering radical dimensions within the biblical text and historical tradition and cultivating an awareness of and appreciation for ecological alterity and ontological multiplicity.[9] However, what distinguishes Wallace’s work is the way in which he particularizes – that is, makes concrete – the animism of Christianity. Here, we should note the extent to which his argument is oriented towards and around practical concerns.

Following the approach of writers like Henry David Thoreau, Annie Dillard, and John Muir (whom he explicitly references), Wallace opens each chapter with a piece of personal nature writing and original woodcut illustration by James Larson.[10] In doing so, he grounds the hermeneutical movements of the book in reference to the specific moments from his own life, such that the these personal narratives are intended to simultaneously model for and cultivate within the reader “a deep feeling of belonging with our terrestrial kinfolk so that we will want to nurture…the occult relationship between the ‘inner landscape’ of […] spiritual identity and the ‘outer landscape’ of” common nature.[11]

Chapter One – ‘Song of the Wood Thrush’ – establishes the biblical roots for Christian animism. Opening with his anticipation of the wood thrush’s return to the Crum Woods, Wallace recalls the first moment he heard the bird’s “liquid” melody and his frustrated attempts to “lure” the creature to his feeder, declaring that “Earth and heaven come alive with mystery and wonder when I hear the thrush’s ethereal song…open[ing] to me the beauty of the Crum Wood as…sacred forest.”[12]

Throughout the chapter, Wallace moves out from the monastic song of the wood thrush to encounter God’s “fleshly identity” as a “fully incarnated being who walks and talks in human form, sprouts leaves and grows roots in the good soil of creation, and – clothed in feathers and flesh – takes flight and soars through the updrafts of wind and sky.”[13] Here Jacob’s wrestling companion, the burning seneh at Mount Horeb, the rûach elohim of creation story, and the descending rock pigeon of Jesus’ baptism are embraced in and for their material subversion of the boundaries between the divine, human, animal, and vegetal.[14]

As Wallace writes, “What strikes me as common in all three of these stories is that God – as avian, human, and vegetal, respectively – is biologically elemental…If God was the creation bird in Genesis, the night brawler in the Jacob story, and the fiery thicket in Exodus, then could not the birds, people, and plants among us today be God-in-the-flesh once again?”[15] Indeed, what distinguishes Wallace’s argument from other environmentally oriented interpretations is his insistence that in these moments God is a burning bush or feral pigeon.

Thus, when Luke describes the heavens opening and the Spirit of God descending like a dove, the phrase hos periteran (“as a dove/pigeon”, “like a dove/pigeon”) must be read appositionally – in this moment, the Holy Spirit manifested itself in the dirty feathers and the feral sensibility of a common rock pigeon of Galilee, just as it manifests itself in melodic thrush of Crum Woods.[16]

Chapter Two – “The Delaware River Basin” – immerses the reader in the practical consequences of “global dying.”[17] Introducing the reader to Carol French, a local dairy farmer from Pennsylvania, Wallace describes the impact that industrial fracking has had on the health of French, her family, her animals, and the land. From polluted water wells and mysterious rashes to broken families and ravaged landscapes, the “nightmare” of hydraulic fracking is revealed as an “environmental crisis” and “human disaster.”[18]

Asserting that “there is no core distinction between climate change, habit loss, and social justice,” Wallace focuses much of this chapter on questioning the “root metaphors” that we use to understand, imagine, and talk about our relationships with local ecosystems.[19] Drawing on Martin Heidegger’s contrast between the “bringing-forth” of poiesisand the “setting-upon” ofmodern technology, Wallace contends that “Life itself has its own transformational rhythm or kinetic artistry…[such that] a milkweed plant pushing forth into full blossom or a Monarch butterfly metamorphosing into a winged insect, left to their own devices, are ever-changing examples of the process of bringing-forth.”[20]

While Heidegger’s analysis of modern technology has often been interpreted, superficially and incorrectly, as an expression of Luddite allergy to technology qua technology, such a reading does not account for the nuance and complexity of his thought. In demonstrating the different ways in which technology reveals the essence of a being or thing, Heidegger seeks to impress upon us the fundamental relationality inherent in all forms of poetic creativity and technological craftwork. Accordingly, Wallace reads this work as demonstrating the possibilities and value of a “biomimetic” disposition.[21]

Here, Wallace offers a particularly creative reading of shamanistic healing practices of Jesus.[22] Commenting on the scene from John 9, in which Jesus heals a blind man with a poultice made of spit and dirt, he writes: “Jesus actualizes God’s power by mixing his salvia with the soil…The Jerusalem soil is ready-made for Jesus to realize its inherent medicinal power to heal the blind mind. Here Jesus’ techne skills comes to the fore. Spitting on the ground, Jesus creates a sticky, wet salve that he applies to the man’s face and then tells the blind man to wash his face in the Siloam pool, wherein the man experiences full sightedness for the first time in his life.”[23]

In this “incantory gesture” Jesus performs what Wallace, drawing on the work of Julia Kristeva, describes as a kind of “holy abjection” – the destabilization of the boundaries between humanity and nature, purity and filth, sacred and profane through a kind of quotidian anointing.[24] In this, Jesus reveals an embrace of and openness toward the inherent vitality and generativity of the earth. Similarly, in recognizing and embracing this ontological porosity, Wallace believes (and hopes) that we might exclaim “Lord God!” in the presence of the sensible Kingdom of God and, in so doing, enter into a biomimesis of the healing grace of creation.

Chapter Three – “Worshipping the Green God” – focuses on the ritual acts of praise and reverence. Wallace is teaching a Religion and Ecology course at Swarthmore and has asked his class to participate in the neopagan ritual “A Council of All Beings.”[25] Encouraging his students to imagine themselves as being “summoned” and then “becoming” a woodland creature, Wallace seeks to “foster compassion for other life-forms by ritually bridging the differences that separate human beings from the natural world.”[26] During one particular class period, he and his students are “visited” by a great blue heron:

We were spellbound. Flying with its neck back in a gentle horizontal S curve, its blue-black fully extended, and its long gray legs ramrod straight and trailing behind, the heron darkened the sky above our heads and landed in the shallow water of the creek…Spontaneously, we jumped up from the meadow and walked heron-like – silent, hands held at our side, strutting in the tall grass – toward this imperial creature…My class and I now felt, it seemed to me, that our modified neopagan shape-shifting practice had prepared us for a connection – a spiritual connection – to a regal bird whose presence electrified our gathering with agile dignity and rhythmic beauty.

The avian visitation impresses upon Wallace the intersection of religious ritual, nature preservation, and the sacred character of the more-than-human-world. Here, the question that motivates his reflections is the possibility (and acceptability) of worshipping nature as divine. Appropriating Paul Santmire’s “metaphor of fecundity”, Wallace emphasizes particular examples of “divine enfleshment” through Christian history. He focuses specifically on Jesus dwelling amidst the “thin places” of heaven-earth porosity, Augustine’s environmentally oriented natalist theology, and Hildegard of Bingen’s viriditas theology of folk healing as a means of demonstrating the “classical” foundation for worshipping “God-as-nature.”[27]

Chapter Four – “Come Suck Sequoia and Be Saved” – is perhaps the most interesting, primarily in the way it deviates from the previous chapters. That is, whereas chapters one through three establish a biblical and historical argument for Christian animism by interpreting and appropriating explicitly religious texts and/or figures, chapter four focuses on what Wallace describes as John Muir’s Christanimism.[28]

Considered by many to be emblematic of a respect and appreciation of nature for its own sake, Muir’s legacy is nonetheless complicated, particularly as it pertains to the creation of the National Park System and his prejudice disregard of the Ahwanhneeche as “unnatural” and “unclean.”[29] Wallace describes Muir’s attitude to Yosemite’s indigenous peoples as a “noxious” and a “stain”, yet nonetheless considers Muir’s “vision of a divinized world [as] desperately needed.”[30]

While his discussion of Muir’s creative appropriation of biblical language and imagery is informative – he contends that Muir is simultaneously “an animist and a biblicist” – it is the section on Muir’s “Sequoia Religion” that is truly fascinating and reveals the depth and breadth of Wallace’s own hermeneutical techne.[31]

Quoting Muir’s “Lord Seqouia” letter to Jeanne Carr in full, Wallace describes the piece as a “theo-poetic feast – a running biblical-cum-naturalist commentary.”[32] In order to feel the force of Muir’s language and Wallace’s interpretation, consider the following:

“Some time ago I left all for Sequoia and have been and am at his feet, fasting and praying for light, for is he not the greatest light in the woods, in the world? Where are such columns of sunshine, tangible, accessible, terrestrialized?”

“But I am in the woods, woods, woods, and they are in me-ee-ee. The King Tree and I have sworn eternal love – sworn it without swearing, and I’ve taken the sacrament with Douglas squirrel, drunk Sequoia wine, Sequoia blood, and with its rosy purple drops I am writing this woody gospel letter.”

“Come suck Sequoia and be saved…I wish I were wilder, and so, bless Sequoia I will be. There is at least a punky spark in my heart and it may blaze in this autumn gold, fanned by the King.”

According to Wallace, these passages embody – they incarnate – the discursive and ontological porosity that lies at the heart of Christian animism. As with the biblical narrative of Jesus baptism, Muir’s reverent testimony for “Lord Sequoia” is not an allegory or metaphorical gloss but rather “a rapturous vision of a fleshy religion, an earthen-intoxicated-therapeutic-sexual religion…[that beckons us] to repent of your indifference and hostility to nature’s bounty and come follow me into the loving embrace of forests and rocks, waterfalls and meadows, great cranes and water ouzels.”[33] In Muir, we are witness to a prophecy of dendritic divinity and arboreal be-longing.

Chapter Five – “On the Wings of a Dove” – is in many respects a lament for the profound loss that has accompanied our “cultural progress.” Wallace describes growing up in a Southern California not yet “colonized” by suburban development and surrounded by the incense of wild sagebrush and the vitality of a robust ecosystem.[34] He writes, “My memory is of a fragrant plant whose spiritual, medicinal, and gustatory properties are woven together in a sensual experience of deep pleasure and reassuring comfort and joy. And my sadness is that the daily delight I experienced in drinking in the pungent aroma of this feeling has been largely attenuated, if not soon wiped out altogether, by the expensive sprawl of the California Southland.”[35]

As a personal example of the devastating species and habitat loss that is characterizing the Sixth Great Extinction, Wallace wants to consider whether the non-sentient matter of “rocks, bodies of water, trees, and other plants” can “experience pain and loss?”[36] Drawing on James Lovelock’s “Gaia hypothesis,” he returns once more to the Genesis narrative, noting the active verbs – “cries out”, “open its mouth and swallows”, “curses”, “refuses to give of its strength” – that the biblical text uses to describe the response of the ground to Abel’s murder.[37]

He concludes the chapter with a detailed narration of his and his wife’s pilgrimage to Spain to walk the Camino de Santiago. The two of them have been hiking along the Cape de Creus and have arrived at the Sant Pere de Rodes monastery and Sant Onofre hermitage.[38] They are “hot, sweaty, parched, exhausted” and are graciously refreshing themselves in the “bubbling wonder of the Saint Onuphrius spring.”[39] As Wallace reflects on the “living testimony to creation’s boundless ever-flowing largesse”, he encounters the offering of “wave after wave of sagey fragrance.”[40] He writes, “Breathing fully and inhaling deeply, I am gifted with a heady bouquet that refreshes my body and uplifts my spirit…Now time runs backward, not toward the chaos of biblical apocalypticism but toward the aromatic balm, carried on nighttime breezes, that floated gently through my California bedroom many years ago.”[41]

Through this prayerful sauntering, Wallace is reminded of the feral vitality of the natural world and laments the profound violence that is inflicted upon the divine-body of the earth. As God is incarnate in the feathers and beak of the rock pigeon so God is crucified in the annihilation of the passenger pigeon.[42] The question remains – do we have the sense-ability to recognize this suffering and the compassion to respond?

The center place that Wallace gives to the figure of the “animal” in general, and birds more specifically, is compelling and in many ways we can read his work as a creative example of “animal theology.” Moreover, whereas someone like Andrew Linzey approaches the place of animals in Christian theology from a primarily ethical-moral perspective, focusing in particular on the ways in which our treatment of animals both reflects and shapes our theology, the ontological dimension of Wallace’s argument emphasizes the multiplicity of ways in which God “becomes/is” an animal – divine presence is the bird. It is curious then that he does not appeal more directly to some of the recent developments in critical animal studies, particularly considering his previous engagement with the work of Jacques Derrida.[43] Incorporating insights from this field would only strengthen his argument, but their absence is not a fundamental weakness.

Where we could offer a more pointed, yet constructive, criticism is with regards to the consequences of using the term “animism” as a conceptual framework for the embodied presence of God throughout creation. That is, while Wallace accounts for non-animal expressions of divine becoming – the burning bush, Lord Sequoia – perhaps his overwhelming focus on “animality” risks unintentionally perpetuating the ontological boundaries that, he argues, “divine incarnation” subverts.

Using the term “animism” to describe the dynamic, vibrant life of creation is understandable when accounting for those creatures are more perceptibly “animate” – birds, burning bush, nighttime brawler – but I wonder whether it is limited with regards to those beings not so easily described and sensed in such terms. From Wallace’s perspective, this move is appropriate precisely because it connects two terms or ideas – “animism” and “rocks” – that are not ordinarily associated with one another. However, while he questions the ontological binary of the organic/inorganic and the imposition of static passivity upon much of material reality in his reflection of the rock wall outside his study, we must consider whether “animism” limits our ability to encounter stones with the kind of ontological openness the Wallace emphasizes? Consider Jean-Luc Nancy’s analysis of Heidegger’s description of the “stone” as worldless:

The stone, no doubt, does not ‘handle’ things…But it does touch – or it touches on – with a passive transivity…The brute entelechy of sense: it is in contact…There is not “subject” and “object,” but, rather, there are sites and places, distances: a possible world that is already a world…The concrete stone does not “have” a world – but it is nonetheless toward or in the world in a mode of toward or in that is at least that of areality: extension of the area, spacing, distance, ‘atomistic’ constitution. Let us not say that it is ‘toward’ or ‘in’ the world, but that it is world…Thus, no animism – indeed, quite the contrary…The stone does not ‘have’ any sense. But sense touches the stone: it even collides with it, and this is what we are doing here…Sense, matter forming itself, form making itself firm: exaction and separation of a tact.[44]

We need not dwell long on Nancy’s comment but rather move out from it to consider whether the ascription of “animism” or “life” to the stone somehow elides its physical particularity. Here I want to focus on his connection of “possession” (having) with “activity” (animism) in considerations of “realization” (entelechy) as “encounter” (contact). For Nancy, the ek-sistence – the standing out or presencing – of the stone is not accounted for in its “active possession” of a world, but rather occurs at the sheer materiality of our liminal touching.[45]

Accordingly, if “animism” is the flattening of “commonplace ontological distinctions between living/nonliving or animate/inert along a continuum of multiple intelligences” such that existence is alive-ness and sentience “according to [a being’s] own capacities for being in relationship with others”, then how do we understand or imagine the capacities of stone?[46] That is, when Wallace describes living rocks as “vital structural elements in the geochemical process that support my and my family’s existence [and] holds together my immediate niche within the larger eco-zone I inhabit”, is he unintentionally perpetuating a quasi-utilitarian description of the rocks?[47]

Does the language of “structure” rehearse the lithic as foundation, and thus inanimate and passive? Indeed, do our typical associations of “animism” with “life” or “living” not reintroduce a boundary between living/nonliving? Why, if “animism” is a dissolution of such boundaries, should we emphasize the “animality” of God? Should our recognition of lithic incarnations of divine presence be dependent on a conceptual framework that emphasizes, if not privileges, animality? I suspect that Wallace does not support any sense of “lithic inferiority” and in many ways he is reading “animism” against our preconceived or established traditions.[48]

Yet I think we must also consider the extent to which, as Jeffrey Jerome Cohen contends, stone “trips us up, challenges, intensifies, remediates, thwarts” in its “inexhaustible mystery and provocative vitality.”[49] Perhaps the ascription of life or animacy to the stone helps us recognize its incarnational possibilities, but perhaps we should also attend to its non-possessive capacity to form – that is create – the spaces of contact in/through its acute physicality.

That is, the “transitive firming” – the material crossing over – of the stone, apart from its life or non-life, can itself be considered as constituting an embodied porosity. Perhaps the stones do “hold together” Wallace’s eco-zone, but our recognition of this point may not be dependent on the category of “animism.” Perhaps “animotheism” limits our openness to “lithotheism.”

Such questions are meant to be constructive indications of how we might expand on Wallace’s creative, insightful argument for Christian animism. When God Was a Bird is an invaluable contribution to a growing and necessary dialogue between religion and environmental studies. The combination of personal nature writing, biblical hermeneutics, and constructive ecotheological reflection offers the reader an engrossing narrative of how and why “Christianity animism” can and should contribute to critiques of and resistance to existential disembodiment, ethical detachment, and environmental despoliation. After reading this text, I returned to my front porch, looked at the rock pigeons across the street, and thought “There is God.”

Scott McDaniel is an Adjunct Instructor of the Department of Philosophy at the University of Dayton. His research deals with religion and theology as they intersect with modern thought, material culture, and environmental studies.

______________________________________________________________________________

[1] Mark I. Wallace. When God Was a Bird: Christianity, Animism, and the Re-Enchantment of the World. (New York: Fordham University Press, 2019), 2.

[2] Lynn White, Jr. “The Historical Roots of Our Ecologic Crisis”, Science, New Series 155, No. 3767 (1967), 1205.

[3] Ibid., 1205-1206.

[4] Ibid., 1206-1207.

[5] Wallace, 1.

[6] Ibid., 41-42

[7] Ibid., 2, 14.

[8] Ibid., 2, 5, 14.

[9] One of the clearest examples of this trend is the work of Catherine Keller, specifically The Face of the Deep and Cloud of the Impossible, both of which propose to situate theological discourse – speech of and about “God” – within the manifold becoming of our entangled relationality. Catherine Keller, The Face of the Deep: A Theology of Becoming. (New York: Routledge, 2003) and Catherine Keller, Cloud of the Impossible: Negative Theology and Planetary Entanglement. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2015). See also: Divinanimality: Animal Theory, Creaturely Theology. Ed. by Stephen D. Moore. (New York: Fordham University Press, 2014) and Laurel Schneider. Beyond Monotheism: A Theology of Multiplicity. (New York: Routledge, 2008); for an explicitly biblical focus see Wes-Howard Brook. Come Out My People: God’s Call Out of Empire in the Bible and Beyond. (Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 2010).

[10] Wallace, 17.

[11] Ibid., 17, 158.

[12] Ibid., 20-21.

[13] Ibid., 23, 22.

[14] Ibid., 22-23

[15] Ibid., 24.

[16] Ibid., 30.

[17] Ibid., 49.

[18] Ibid., 51-53.

[19] Ibid., 53-54

[20] Ibid., 55; emphasis added.

[21] Ibid., 59.

[22] Ibid., 67.

[23] Ibid., 63.

[24] Ibid., 66, 64.

[25] Ibid., 82.

[26] Ibid., 82.

[27] Ibid., 91, 98, 105, 112.

[28] Ibid., 113.

[29] Ibid., 114, 116-117.

[30] Ibid., 118.

[31] Ibid., 130, 133.

[32] Ibid., 135.

[33] Ibid., 138.

[34] Ibid., 142.

[35] Ibid., 142-143.

[36] Ibid., 145.

[37] Ibid., 149.

[38] Ibid., 154.

[39] Ibid., 155.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Ibid., 155-156.

[42] Ibid., 165.

[43] See Kelly Oliver. Animal Lessons: How They Teach Us to Be Human. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009) and Matthew Calarco. Zoographies: The Question of the Animal from Heidegger to Derrida. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2008) for substantive and accessible introductions to the figure of the animal in the Western Continental philosophy.

[44] Jean-Luc Nancy. The Sense of the World, trans. Jeffrey S. Librett. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997), 61-63.

[45] Nathan Brown. The Limits of Fabrication: Materials Science, Materialist Poetics. (New York: Fordham University Press, 2017), 55.

[46] Wallace, 9.

[47] Ibid., 146.

[48] Ibid., 9. His reference to George Tinker’s contention that “rocks talk and have what we must call consciousness” indicates a kind of capacious humility and openness in the presence of stony things.

[49] Jeffrey Jerome Cohen. Stone: An Ecology of the Inhuman. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015), 11, 12.