The following is the second of a two part series. The first can be found here. The entire article appears in Issue 22.1 of the Journal for Cultural and Religious Theory.

The Ethical Relation as Language

There is that which he calls ‘language‘. He writes: “Language does not belong among the relations that could appear through the structures of formal logic.”[1] That is because “it is contact across a distance, relation with the non-touchable, across a void.”[2] It is about „a language of trauma in order to evoke the way in which sensibility is always already affected by the Other.“[3] How come that we are always already affected by another? — well, there are different meanings of language in the theory at hand from what we have so far understood: there is Body Language (which will be looked at more closely in the next section), then, there is what Lévinas calls ‘Expression’ as well as Speech, going off ‘body language‘ drawing a connection to the necessity of trauma and touch, too.

“The ethical relation, the face-to-face, also cuts across every relation one could call mystical […] Here resides the rational character of the ethical relation and of language. No fear, no trembling could alter the straight-forwardness of this relationship, which preserves the discontinuity of relationship […]” (TI 202f.) “The ethical relation cuts across every relation one could call mystical” The face to face must be honest.[4] That is a given. But it, in the face of trauma or after traumatisation, it is impossible not to be. This is what Levinas writes: “Die ethische Beziehung, das Von-Angesicht-zu-Angesicht, hebt sich ab von jeder Beziehung, die man mystisch nennen könnte.”[5] (‘It cuts across every relation one could call mystical‘) It is rare and real. We will find an issue with this in ‘Transcendence and Relation‘.

“Here resides the rational character of the ethical relation and of language.”Here, we find the understanding of ‘language’ that invites the rational component in. It is a particularly (because of the rational component?) straightforward way of relating: a way of bridging, perhaps? The rational character of the ethical relation and of language resides in the face-to-face, in the seeing hence recognising and then addressing the face. This means acknowledgement through spoken and verbal word? The direct confrontation of expression? The conscious aspec. “No fear, no trembling could alter the straightforwardness of this relationship which preserves the discontinuity of relationship..

And it is that straightforwardness that preserves the discontinuity of the relationship. Here, we can find an indication to Lévinas‘ traumatised body: him writing about ‘fear‘ and ‘trembling‘ as bodily (stress) reactions to the encounter, to the face-to-face. Why does he write about the discontinuity of relation here? — he writes about discontinuity because he differentiates between the two ways that two people can encounter each other: ‘saying‘ something and having already ‘said‘ something (else). There are two different ways of ‘saying’ addressed here; one where the body speaks, another the mind.

Herein lies the difference between the initial relation and the ethical relation: the initial relation so happens to both parties — it is instinctual and emotional (but in fact seems to go beyond the emotional component) connection, an unsayable in-between where that which is used by Lévinas to describe what happens has another meaning as that which it usually does. Language and speech are words to describe a calling of the other to the same. It is a way to describe a physiological resonance. This resonance is interrupted in the moment that the connection becomes conscious; at least it is that which the quotes indicate. Once the rational (reflective) element is also there, the ‘relation‘ as Lévinas calls this, is interrupted. It is in ‘discontinuity‘. Why? Because it is brought to consciousness that there are other aspects to a living being that must be considered. From this moment onwards, anything that happens must be justifiable. And this justification is morality, is ethics. From the moment that one person realises the demand that the Other is addressing the Same with, they must respond. How do they respond?

Hineni is a term from the Jewish tradition; a concept used to describe the ethical encounter. It is translated from Hebrew as “Here I am”; fully present, letting go of my own needs, fully and completely open to the Other and to the present moment; meaning the Other in the present moment. What the attitude of hineni opens up: the borders between oneself and the other are moved because due to hineni, I allow myself to be emotionally touched by the other and try to empathise as fully as possible; physically, somatically, emotionally. It is “the sensible.”[6]

Levinas himself writes that the concept of hineni is grounded in a sense of responsibility that has a pre-cognitive character; he argues that “responsibility…has no cognitive character.” For him, “Responsibility is not an esoteric knowledge or capacity but an embodied memory of the other.”[7] This embodied memory is similar to the co-regulation-scheme that somatic experiencing with Peter Levine works with, too. It is the nervous systems’ co-regulating each other automatically when two people are together.[8]

It is a kind of embodied empathy that Levinas takes one step further, saying that it is an embodied responsibility. (It is interesting however why he says that it is responsibility. This deviates from Levine’s account of course. Levine does not claim that it is the other person per se that traumatises.) It requires us to have “a psyche oriented toward the Other, the very configuration or shape of their selves being lived out as hineni, a perpetual Here I am (me voici).”[9] And it is that which evokes a responsibility in the Same through the Other and for the Other. This responsibility comes from sensing a demand, a vulnerability, a need. This is where we recognize each other beyond difference as the focus lies on the bodily presence.

Identifying Trauma in Lévinas’ Ethics at hand (dissociation in Otherness, the non-relation, focusing on the bodily encounter as well as being present with hineni)

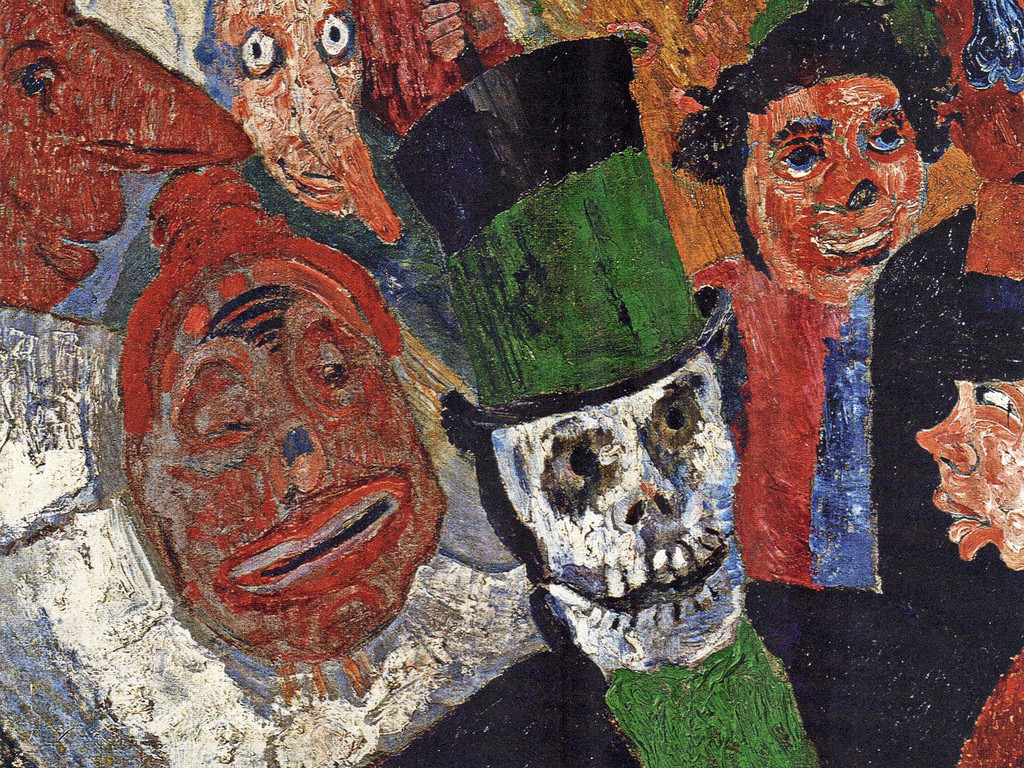

After having gone through three topics in Totality and Infinity, we can identify trauma in both the topics of choice. Not only that, but also in the content. Firstly, his focus on Alterity and Otherness. This is an indicator for a traumatic experience because, as was mentioned in (I.), it is the most alienating experience that humans can have. Their reality shatters, and they are overwhelmed and alienated from themselves (their bodies) and others, too (see reference above on Bessel van der Kolk). Often this is due to dissociation — one of the consequences of a traumatic experience (as mentioned above). Lévinas’ focus and also the foundation for his ethics may be due to his own dissociation. Another indicator for this may also be him speaking of relationship and also the ‘discontinuity’ or ‘non-relationship’ (see above) — which refers to the inability to relate after trauma.

Further, the claim on the ‘pre-original’ encounter meaning bodily presence with one another as well as presence itself is d’accord with the methods of somatic experiencing trauma therapy — and isn’t it interesting that it is this attitude that Lévinas asks for is what is practiced trauma therapeutically?

On the Psychosomatics of Lévinas’ Ethics (Psychosomatics, Embodied Cognition)

As indicated in the previous section, Lévinas’ ethics shares a conceptualisation and method with a leading trauma therapeutical method. This also reflects his own trauma.

Here we are of course particularly concerned with psychological trauma rather than physical one, and working with the fact that the psychological traumatisation affects the rest of the system as well. It is an attempt to bring philosophy into the therapeutical field, and specifically since we are dealing with trauma as the ultimate other, it would be trauma-therapy. Since it is such an encompassing phenomenon and thus must be treated in this vastness, philosophy might be able to help. Hereby let psychosomatic medicine be defined, as “relating to a physical problem caused by emotional anxiety and not by illness, infection or injury.”[10] To be more precise:

- “relating to, concerned with, or involving both mind and bod

- “relating to, involving, or concerned with bodily symptoms caused by mental or emotional disturbances”.

And since “psychosomatic medicine requires a philosophy that surmounts mind-body-dualism,” it is that which I hope to provide with the following paragraphs in considering trauma, then (trauma) therapy, and methods based on Levinas’ philosophy for psychosomatic trauma (that is, any trauma).

Such demand, vulnerability, need can be sensed when reading Lévinas‘ text, namely “the language of the inaudible, the language of the unheard of (…) Scipture!“[11]

The Socio-Somatic Effect: Embodied Cognition

According to Lévinas, it is language that constitutes relation, and perhaps we are somehow in relation by reading him. He is verbalising something that cannot be put in words — which is the reason why it is so abstract. He is processing his trauma which is why Otherness is the central focus (as we have seen earlier, trauma can be considered the ultimate Otherness).

It is psychosomatic because Otherness is written into his writing. This may be due to le autre being an „inner representation of the invisible and inaudible physical reality“[12] that he was living with which found its way into writing.

D´Accord with the concreteness that philosophy can have as we can witness in Lévinas‘ writing, „our physiology provides the concepts for our philosophy,” Lakoff wrote in his introduction to Benjamin Bergen’s book Louder than words: The New Science of How the Mind Makes Meaning (2012). Marianna Bolognesi, a linguist at the International Center for Intercultural Exchange in Siena, Italy, puts it this way:

The classical view of cognition is that language is an independent system made with abstract symbols that work independently from our bodies. This view has been challenged by the embodied account of cognition which states that language is tightly connected to our experience. Our bodily experience.[13]

So, we must look closely at the body (of thought) in this investigation; also, in the literature research — as “the abstractions and generalisations of phenomenology cannot yield the fine-grained texture of lived experience”[14] but we ought to develop a sensibility for the fine-grained nuances of lived experience and the expression of exactly this experience by understanding the literal/physical/somatic potential that abstract and general phenomenological language holds. We can do this by investigating the written thoughts of holocaust survivors (post-holocaust philosophy) – that may be seemingly abstract, however a concrete reflection of the somatic state(s) if we rely on the recent findings of embodied cognition.

Now, of course there is a difference in reading Levinas and considering the relation between therapist and client or subject and traumatised subject. One of these differences is of course that, although Levinas somatic state may be sensible by reading him, we cannot be present with his whole person, only with a medium. Or is that the only way with which the traumatised can be present anyway? Never fully, but through a medium?

There are aspects that I would like to address, both regarding Levinas’ account of trauma in relation. This refers to the “face-to-face” (Antlitz) encounter and its effects (which unfortunately cannot be elaborated on here)We are thinking about Levinas as the trauma patient and the parallels between studying his philosophical work and being with a traumatised person, or phrase it differently: being with a traumatised person by reading their words as opposed to but also physically working with them.[15]

Levinas‘ conception of Otherness helps us understand. Lévinas claims that „the relationship between the Same and the Other is language“ in Totality and Infinity, what is meant by the Same, what is meant by the Other, what is meant by relationship?, and how can the findings (psychosomatics of Lévanas’ ethics) be connected/applied to enhance Trauma Therapy?[16] So far we know that the Same is before the trauma, and the Other is (after) the trauma. The trauma of astonishment is necessary when we are in the world — it is physical, emotional, and psychological touch. It is language that is both physical and verbal.

Summary

When Lévinas claims that „the relationship between the Same and the Other is language“ in Totality and Infinity, what is meant by the Same, what is meant by the Other, what is meant by relationship? And how can the findings (psychosomatics of Lévanas’ ethics) be connected/applied to enhance Trauma Therapy?[17] WE have considered over the course of this thesis:

The Levinasian conception of otherness by looking at the quote: “The relationship between the same and the other is language” with the question posed right at the beginning of the investigation whether or not relationship is possible in Levinas thinking considering that he was writing out of a traumatisation (which makes one unable to relate) — because we are tied to our bodily symptoms that must be lived out, otherwise our thought and entire lives will revolve around that trauma (which arguably is what happened to Lévinas and his writing when it comes to these topics). It turns out that language is both bodily language and somatic expression as well as verbal language as expressed through writing.

We have not explored speaking per se, but have gone straight to looking at ‘the face’ which is that which speaks by simply being present, by me simply noticing it. It seems that the bodily/physical/somatic aspect are closely connected to the cognitive and verbal aspect in Levinas‘ philosophy. This is especially the case when we consider embodied cognition as well as the ways that we can be touched without being touched physically. It is perhaps this dimension that he tries to break and keep open when he considers language and relation (for, where is the difference, really?) in Totality and Infinity. It is the physical boundaries that are broken apart through that which is not physical for us, ungraspable to us: emotion. It is that which must simply be lived out and experienced — with others.

Levinas roots his philosophy in a lived ethics and a theory of alterity; of the connection between body and mind, between inner and outer, between me and them. None of the poles meet unless a common language is established — that we are only receptive towards if we open up to each other (which is something we can never prepare for). He extensively looks at this in Totality and Infinity, his habilitation from 1961 — translated into English by Lingis in 1969. It is one of the first works that he writes in which trauma is so overly present.

Concluding Thoughts

The new approach to trauma that we gain through Lévinas is that if we understand that trauma is ever-present, we open up to each other; we are in touch with our wounded selves to be more fully grounded in the present. Each one of us. Levinas’ approach is one that touches on the “movement of the soul”; focusing on the relational spaces that we together can create if we meet each other with the ethico-spiritual attitude that he calls “hineni” in which we each become the embodiment of God, of an infinite being. Hineni is a lived and felt memory of the Other. It is an embodied memory of the responsibility that I have towards the other. It cannot be rationally explained, but only sensed.

In Totality and Infinity, Levinas writes that “justice is the right to speak.”[18] It is the face that speaks before anything else can; and it is seeing the face that implies speaking. This kind of ‘speech‘ is an instinctual one, one that requires what Levinas has called ‘the sensible‘, needed when we work with trauma. Psychological trauma automatically is stored in the body as it is connected to emotion and automatically finds its way into writing. Psychological trauma is emotional trauma and thus it is embodied. It must be lived out psycho-somatically, with an “affective witness,” in the sense-perceptual dimension, in order to discharge and co-regulate[19] — which, to a certain extent, is possible when just reading a text if we take embodied cognition seriously.

This is what we have explored about hineni, which adds a top-down-dimension to the other trauma-therapeutical methods that we have discussed. „it is this attention to the suffering of the other that, through the cruelties of our century (despite these cruelties, because of these cruelties) can be affirmed as the very nexus of human subjectivity to the point of being raised to the level of a supreme ethical principle,“[20] as we can read in Entre Nous/Useless Suffering. This ethical principle comes from and is a possiblity of healing trauma — if therapists, aquaintances, friends,.. take seriously what Lévinas writes about: HINENI: “Here I am”.

Fully and completely open to the present moment, meaning: the Other in the present moment. If we encounter text with this same attitude, it can have therapeutical effects as well, because a relation is entered from writer to reader and vice versa as well as the mind being in touch with the body and vice versa. Embodying philosophy happens by text itself as well as beyond that — if only we allow ourselves and each other to be present.

So, there is not only the bodily encounter and presence with openness in his theory content-wise, but also a bodily encounter and presence with openness when reading Lévinas’ embodiment.

Magdalena Sedmak s a master’s student at the University of Vienna developing her own approach to a philosophical practice beyond theoretical thoughts and arguments, understanding that any process must be felt, expressed and embodied if it is to be fully lived out, which is the base of somatic-based trauma therapies that she is continuing to study. She focuses on the points of connection (Berührungspunkte) in her work — academically as well as in movement instruction — that allow for the creation of safe spaces within and without, vital for a fulfilled and meaningful life in a turbulent world.

[1] Ibid. 172f.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Newman, op. cit., 92.

[4] Ibid., 291.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Newman, op. cit., 99.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Introduction to Somatic Experiencing via segreece.org.

[9] D.M. Goodman and S. F. Grover, “Hineni and Transference: The Remembering and Forgetting of the Other,” in Pastoral Psychology, 56(2008): 562.

[10] Miriam Webster definition.

[11] Emmanuel Lévinas, E., “Useless Suffering” in Entre Nous, trans. R. Cohen (London: Bloomsbury, 1988), 178.

[12] van der Kolk, op. cit., 280.

[13] Michael Chorost, “Your brain on metaphors”, The Chronicle of Higher Education 61(2014): B6-B9.

[14] Westin, op. cit., 464.

[15] van der Kolk, op. cit. 284; writing helps as we are listening to ourselves while we do.

[16] What does reading Lévinas’ account of the ethical relation in Totality and Infinity tell about the needs of the traumatised? What is the therapeutic relevance and take-home for trauma workers from Lévinas‘ philosophy in Totality and Infinity?

[17] What does reading Lévinas’ account of the ethical relation in Totality and Infinity tell us about the needs of the traumatised? What is the therapeutic relevance and take-home for trauma workers from Lévinas‘ philosophy in Totality and Infinity?

[18] Levinas, Totality and Infinity, op. cit., 298.

[19] van der Kolk, op. cit., 278 about „feeling listened to“ and the change in our physiology due to the activation of the limbic brain.

[20] Op. cit., 84.