Schrijvers, Joeri. Between Faith and Belief: Toward a Contemporary Phenomenology of Religious Life (SUNY Series in Theology and Continental Thought). New York: State University of New York Press, 2016. ISBN-10: 143846021X Hardcover, e-book. 398 pages.

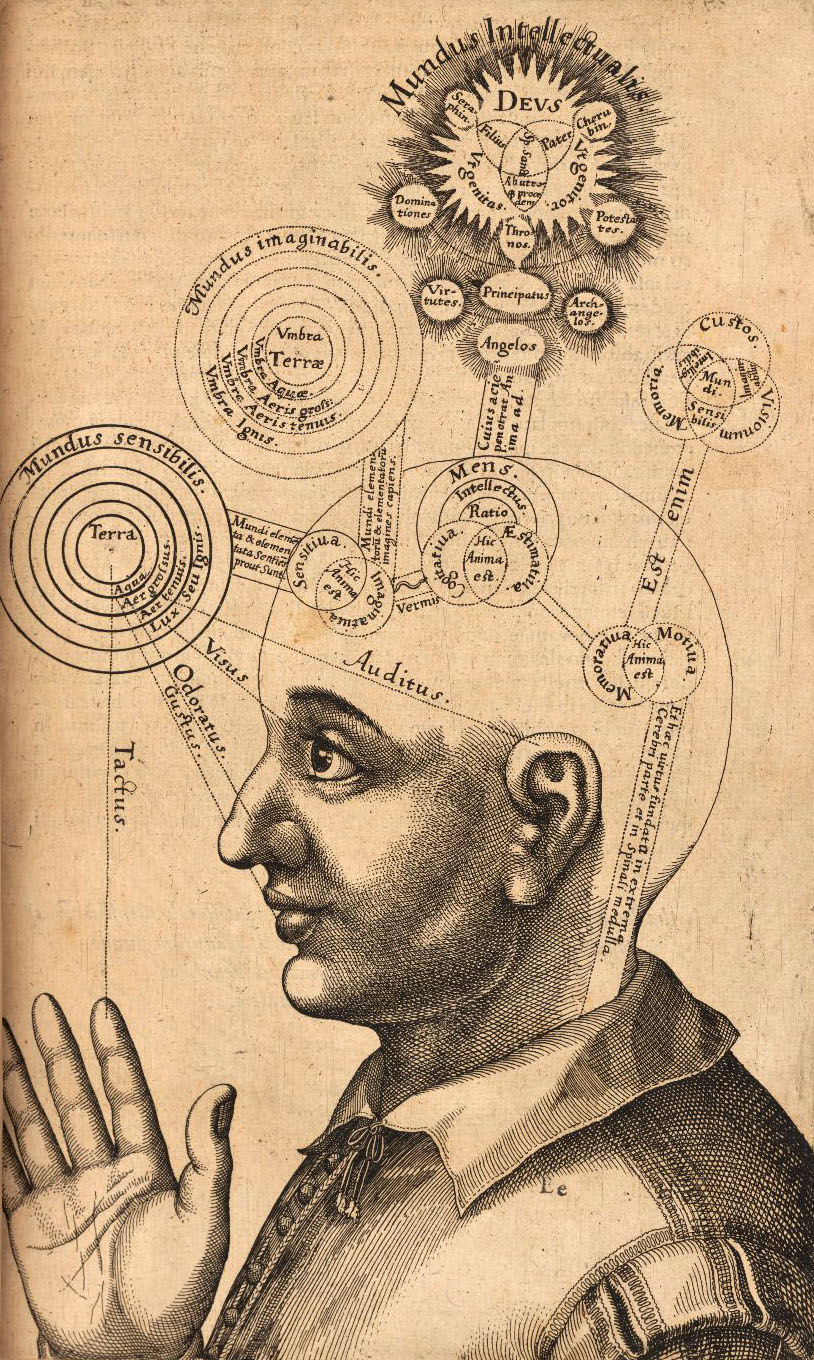

The landscape of contemporary philosophical theology is doing much to confront the human, all too human, ghosts of the death of God. In a secular age increasingly typified by the promulgation of “nones” who remain unaffiliated—or worse (from the perspective of those who find value in the study or practice of religion), absolutely indifferent—to traditional religious offerings, this kind of theology remains invested in expanding what religion might mean to spaces where it no longer seems to apply.

More specific than the equally interesting question of what “secular” means is the question concerning how a “postsecular” religious outlook relates to traditional religious practices. Some, following Badiou, have emphasized questions of practice. Others, following Heidegger, emphasis questions of faith.

As indicated by his title, Schrijvers falls strongly into the latter category. An unflinching exploration of a certain post-Heideggerean line of thought (moving from Derrida and Levinas to Nancy and Caputo) and recovery of one of Heidegger’s under-read contemporaries, Between Faith and Belief: Toward a Contemporary Phenomenology of Religious Life provides an excellent guide through complex theories and theorists who have made an impression on contemporary debates.

Schrijvers’ work in the book largely involves a process that seems akin to sampling in modern music. Less an original composition, he attunes readers to the textures within the respective corpus of the figures he treats: Nancy, Sloterdijk, Caputo, Derrida, Marion, and Binswanger. His course through these figures, individually, is impressive. He finds leit motifs within each figure and threads these in ways that tracks how early works extend into latter works.

One of the book’s not insignificant gifts to the reader is precisely this—an understanding of how different books in individual author’s canons fit into the larger whole within each’s own canon, and also within the field as a whole. Nearly as impressive is Schrijvers’ ability to show interrelations among thinkers, providing a tapestry of connections among thinkers in a narrative arc that shows the dialogical nature of contemporary academics. And so one learns of Levinas, Heidegger, Husserl, and Hägglund alongside Schrijvers’ chosen, which does much to fill in the gaps of contemporary debates.

The book is divided into three parts, distinguished by different spatial paradigms: “without,” “between,” and “within.” Ostensibly, these govern three ways of relating questions of faith and belief. The first part focuses on thinking that describes a faith without (outside, following after) belief (and religion). The focus on this part is primarily on Jean-Luc Nancy’s project involving the Deconstruction of Christianity, with a concluding emphasis on Peter Sloterdijk (in a section that seems most weakly tied into the book’s organization). Schrijvers ends up concluding Part I a bit too quickly by focusing more precisely on problems with each thinker’s system rather than extending those systems forward, a move that seems fair but also somewhat disappointing.

Part II explores the space between faith and belief (and also between strong and weak theology), with an emphasis on Caputo’s theology (as read against both Derrida and Marion). As above, the section is filled with illuminating readings that falter on too weak an initial formulation of what “faith” might mean as a way to more generously explore what Caputo might mean by a religion “without” religion. The conclusion of Part II also shows the inadequacy of Caputo’s path by pointing to the tendency to overlook particulars, both in terms of community and in terms of the particularity of another being—the “moment of incarnation, of an ontic figure filling in the gap between the conditional and the unconditional” (219).

Both part I and part II seem designed to point out “problems” in the respective perspectives described such that part III, focused on Binswanger, will provide a “solution.” Overall, then, the first two headings seem primarily to function as guides to the third—in other words, it is important to understand “without” and “between” as positional contrasts to “within,” rather than positions on their own.

The book truly is framed around part III beginning with the second paragraph of the introduction, which states clearly and accurately that “The book primarily wants to communicate its enthrallment with Binswanger’s thinking of love’s presencing” (xi), and, indeed, the book’s framework pushes readers in this direction. One can hardly fault Schrijvers for this desire: Binswanger’s phenomenology of love, as recounted by Schrijvers, truly is a satisfying alternative to post-Heideggerean thinking.

In fact, one of the great virtues of the book is its reintroduction of Binswanger: the third section of the book, which addresses the flaws carefully named in the “without” and “between” sections. Choosing to introduce Binswanger by means of precise contrast (against Heidegger, against Levinas, against Freud) allows readers familiar with the landscape of 20th century continental philosophy to quickly understand—and likely join in—Schrijvers’ excitement.

Binswanger was a Swiss psychiatrist who became enamored of phenomenology, making the move from Husserl to Heidegger after the publication of Being and Time. Rather than maintain a focus on Dasein in itself, Binswanger focused on what Schrijvers translates as “loving togetherness.” This anticipates Nancy’s phenomenological emphasis on egalitarian communities, which works to expand Levinas’ ethical demand from an “Other” to “Others.”

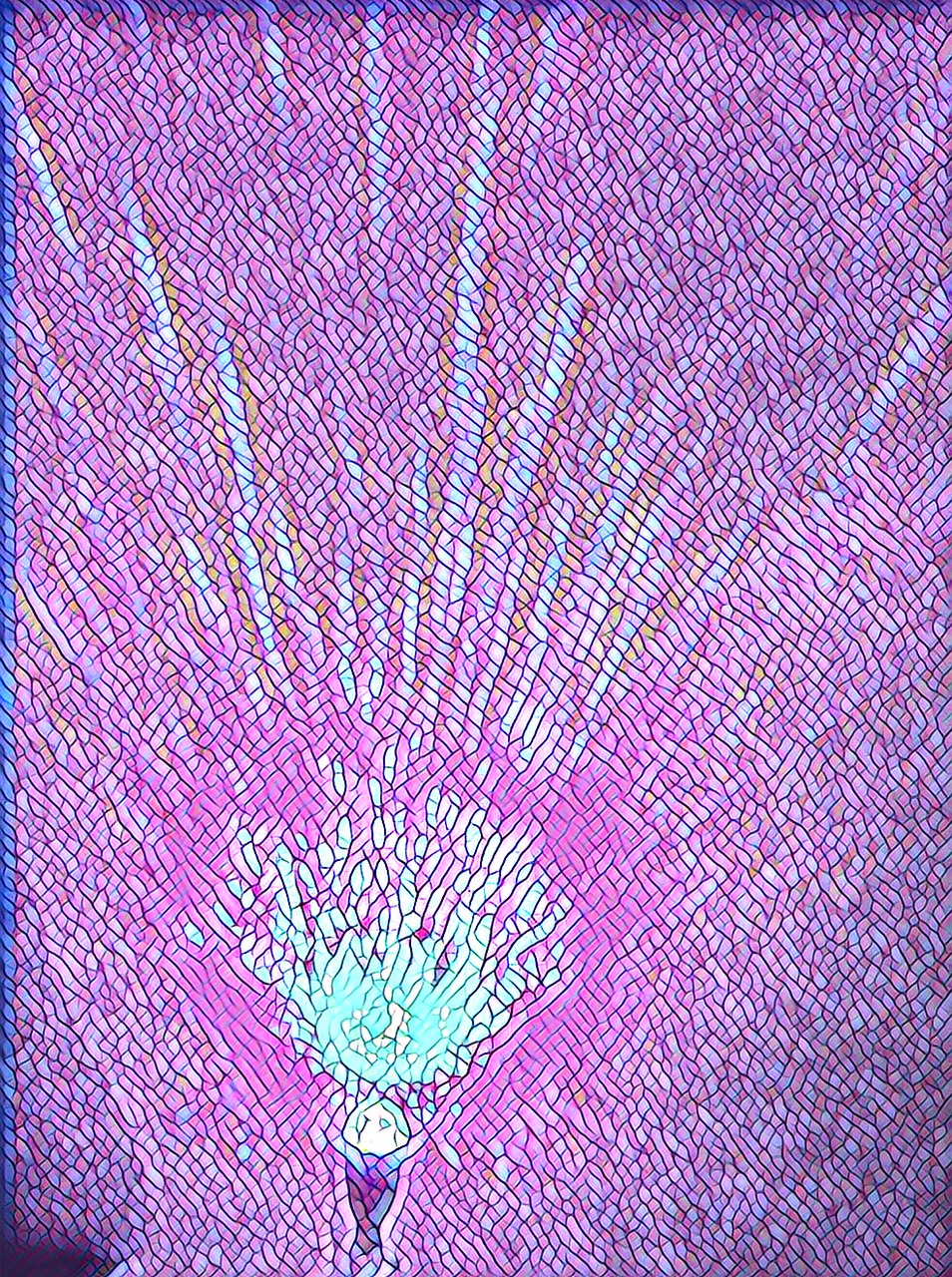

Following the thinking of the poet Von Hoffmansthal, Binswanger, in Schrijvers’ words, shows “the passageway from the ontic embrace to the ontological universality of beings saluting beings” and discloses how “it is love that unites identity and difference” (231) without collapsing differences. Love provides an antidote to Heidegger by presenting a space beyond the world: dissolving all boundaries and differences, love introduces a sense in which world becomes both that which contextualizes the spaces where lovers meet, but also that which love, met, surpasses and redefines.

Love is anchored in a particular beloved, whom Binswanger argues represents “one particular You and You-ness in general” simultaneously. The ontic manifestation of the particular beloved is our entry point into loving—not love—but all beings. This, Schrijvers argues, is where the ontic experience of love merges into an ontology of love—and where Binswanger shows a deficiency in the ontology offered by Being and Time, for “in love, what matters most is not this being that I in each case am and have to be but rather the togetherness that we always and already are, have been, and will be” (240). We encounter being in reciprocity: “I give myself to you because we have given and received ourselves to and from one another” (241).

Schrijvers deftly highlights how Binswanger anticipates many foci within contemporary philosophical theology: how love replaces death as that which posits the equality of all beings, the relation of love to questions of language (and silence) and community, and the question of what friendship means relative to Binswanger’s notion of love. Friendship becomes a form of love that allows for a more independent form of love than loves engaged erotically, a kind of togetherness that still provides a taking part in the destiny of the other, and one that allows for a plurality of “we,” each instance of which remains tied to love’s ontological significance.

Again diverting from Heidegger, Binswanger argues that love is what provides death its significance, and that death does not alter the sense of belonging grounded in the “we” of friends or lovers. This is good, as Binswanger also finds that the self is produced out from love, meaning, in part, that the truth of the self (like the truth of the ground of love) remains a questioning, and a mystery.

The general conclusion of Schrijvers’ book, based heavily on the Binswanger preceding it, provides a preamble toward a contemporary phenomenology of religious life. Although it builds on what precedes it, Schrijvers doesn’t fully articulate all of the potential that comes before. The beginning of the conclusion is important, stipulating (along with Hägglund) that we need to understand that our world is grounded on a lack of being. Whether understood as a lack of love we perceive in the world or the bad conscience with which we believe ourselves to be more open to the Other than we are, the lack of being persists.

Schrijvers writes: “The human being…is in default…because the human being fails to love properly,” which is why the world remains lacking in love. Schrijvers supports this with a meditation on language (through Heidegger, Levinas, and Derrida), finding that the necessity of language means that the possibility of erring about being is co-equal to the possibility of speaking about them properly.

The ontology of lack is important for Schrijvers because, relative to our religious and spiritual condition, it is necessary to conclude that “one does not know about the ultimate. The lack of such knowledge is what gathers and opens onto others who, equally, share such a lack,” although this lack “entails the joy of a humble recognition that no one really escapes such being in default. We all have an equal share of not-knowing” (311).

Schrijvers visits Heidegger’s Phenomenology of Religious Life to find that early Christians engaged in “a continuous attempt to safeguard the “When” of the coming” of God, which problematically rendered salvation as vorhanden, “a matter of instrumentalized, objective time.” Schrijvers walks through Heidegger’s argument, focusing on how inauthenticity blooms in the negative moment when the Christian fears “being unable to endure the wait and of not being granted one’s salvation” (314) and thus engages in a tranquilization that differentiates the saved and the damned.

Schrijvers wants to suggest the alternative of holding to an “unredeemedness” that squares with the “humbleness and the modesty that the phenomenology of finitude of this work prescribes” (314). This keeps salvation as uncertain, especially as it remains humbling to note that Christians are never perfectly so—it’s impossible to “eradicate all instrumentalization when it comes to the question of the divine” (315). This impossibility, for Schrijvers, is what keeps Christians in community with heathens, which opens up a space for dialogue (and a point of community, or commonality) predicated on equality. It’s an inclusive stance, and one that keeps the possibilities of world and salvation as inevitabilities.

Schrijvers wants to suggest the alternative of holding to an “unredeemedness” that squares with the “humbleness and the modesty that the phenomenology of finitude of this work prescribes” (314). This keeps salvation as uncertain, especially as it remains humbling to note that Christians are never perfectly so—it’s impossible to “eradicate all instrumentalization when it comes to the question of the divine” (315). This impossibility, for Schrijvers, is what keeps Christians in community with heathens, which opens up a space for dialogue (and a point of community, or commonality) predicated on equality. It’s an inclusive stance, and one that keeps the possibilities of world and salvation as inevitabilities.

The conclusion is a fitting ending of the book, consistent with the virtues and blemishes of the whole. It provides a nice illumination of Heidegger’s text and draws into the end most of the thinkers whose reflections have inhabited the book. On the other hand, it still fails to provide a clear or explicit position on how this work relates to questions of faith and belief.

This is a disappointment, not only aesthetically (as it weakens the relationship between text and title, defaulting on the title’s promises), but also because it would seem easy for Schrijvers to have made the connections necessary to relate the work to how faith and belief relate. The introduction of Binswanger is a brilliant, but unfortunate, insertion of the space between faith and belief that ends up obfuscating instead of clarifying the nature of that relationship.

Schrijvers makes three formulation of the relation of faith and belief but fails to do much more than assert them. The first is his assertion that “faith without belief is…blind” (77), backed up with a quick example of the virgin birth that shows the role of faith as actualizing the belief’s contents. This, for Schrijvers, trumps Nancy’s argument for the primacy of faith over belief.

What it doesn’t do, however, is account for Nancy’s possibility of faith as “adhesion to itself,” that which maintains itself in enduring as a possibility even when the contents of a belief break or crumble. In other words, Schrijvers is correct in identifying how faith can follow a belief but moves too quickly from the subject to explore its more rich possibilities.

The second claim made about the relation of faith and belief comes at the conclusion of the second section, framed by his analysis of Caputo. Schrijvers asks two questions about the relation of faith and belief, wondering what would happen if we only had extant religious revelations as intimations of a “Christianity to come,” if we could only explore faith through extant beliefs. He concludes as though these were proven: “Then there would be no such thing as a foi that is ‘more pure’ than any other mixture of faith and belief. At best, one would arrive at a less impure faith…mixed with beliefs that one believes are all too improper” (183).

The problem is that Schrijvers has no faith in moving beyond belief, a problem that makes me wish there had been a bit more breadth in the study—looking to the work of Paul Tillich or Paul Ricoeur on the question of faith would have led to a more nuanced sense of the possibilities of faith against belief. One wishes to see how Schrijvers would treat such figures. Even if Schrijvers is not wrong on this point (and I disagree with him on this point: in full disclosure, I have faith that one can indeed move beyond belief), he needs to provide far better argumentation to uphold his perspective.

The third claim about faith is the most confusing. In discussing “Faith in Love” at the end of chapter eight, Schrijvers states: “it is not that you need to have faith to believe Binswanger’s phenomenology here; it is rather that without this belief (in loving togetherness) you will have no (religious or otherwise) faith” (242). It’s at this point that one with a focused interest in matters of faith and belief wish for far more clear distinctions between the titular terms later on.

One could switch “belief” and “faith” in this sentence and have a sentiment closer to Nancy and Caputo—and it is difficult to understand why this is not an equally valid argument to the one Schrijvers presents. Faith, not belief, is what Nancy would connect with possibility and the imagination. When Schrijvers himself concludes on that an ultimate love requires ““a knowing that one does not know about the ultimate stakes” (255), he provides a strong case for how an unknowing that Nancy, Caputo, and Derrida would recognize as “faith” interacts with love—but is less interested in this connection.

Schrijver’s larger point is the importance of love—the actual relation of faith and belief is relatively unimportant—but in dismissing it he misses an opportunity to clarify, and instead confuses, one of the major issues in contemporary continental theology.

Overall, what I feel is most unfortunate about the book—and this is my only significant criticism of it—is the choice to deal so lightly with the titular subjects as to make them almost tangential to the book. In some ways, perhaps, this is the trade off for the depth of reading that Schrijvers offers, or the choice to quilt together a series of readings in ways that illuminate overlaps between them—even if the chosen framework, that of “faith and belief” and a “contemporary phenomenology of religious life” don’t exactly come to the foreground in a satisfying way.

In some ways this makes sense: Schrijvers operates as a DJ, sampling the deep cuts of others into new melodies, rather than creating music of his own. The book itself thus serves best, perhaps, as a helpful foundation for future works about faith and belief or contemporary phenomenologies of religious life.

Daniel Boscaljon received his Ph.D. in Religious Studies (2009) with a focus on modern religious thought and postsecular theology, and his Ph.D. in English (2013) with a focus on nineteenth-century American literature. Boscaljon’s interest in kindling an awareness of wonder and awe in the everyday world, first displayed in his book Vigilant Faith, has grown in his work with the Center for Humanist Inquiries (CHI) and his involvement with thesacredprofane podcast. Currently teaching at both the University of Iowa and Cornell College in addition to his work with CHI and the local arts community, Boscaljon is working on a second book, Gothic Haunts, which will be published in 2017.