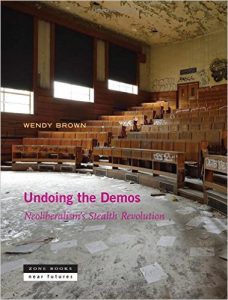

Brown, Wendy. Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution. New York: Zone Books, 2015. ISBN-10: 1935408534. Hardcover. 296 pages.

Brown, Wendy. Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution. New York: Zone Books, 2015. ISBN-10: 1935408534. Hardcover. 296 pages.

Almost every day since Election Day, 2016, a flood of think-pieces, editorials, and election post-mortems have sung a cacophonous and angry dirge. They scold an inept, divided left, and fume at the masculinist, authoritarian right now empowered and validated. American democracy, it seems, is all but buried (or, as researchers at The Economist delicately put it, “flawed”). Yet the identity of these commentaries’ real enemy remains unclear, and even among the left’s clarion voices consensus is hard to come by. The cause of Donald Trump’s ascendency, and the resultant intensification of racism, Islamophobia, and political discord across the country, has born the names populism, white nationalism, fascism, the electoral college, white racism, and—in a growing strain of commentary—neoliberalism.

Neoliberalism’s usual association with technocracy and finance seems off-base as a way of thinking about real estate mogul Donald Trump, the unsophisticated master of what Marxists call “primitive accumulation.” After all, was not Hillary Clinton neoliberalism incarnate? Did she not promise to maintain U.S. interventions abroad, and to center global trade and finance capital in the U.S. economy, all buttressed by watered-down, middle-class cosmopolitanism? And was not Trump, in strict contrast, the neo-fascist candidate? The self-serving autocrat who promised an anti-technocratic, economic-isolationist and xenophobic White House? Trump’s victory prompted Cornel West to speak of “the end of the neoliberal era” in the United States.[1] Others saw neoliberalism as “the deep story” behind Trump’s rise to office.[2] Is neoliberalism’s reign over international politics, once taken for granted, affirmed or thwarted by Trump’s repeated threats against democratic values and process?

Through these pieces and many more, we learn of the analytic potential, and pitfalls, of naming our troubles “neoliberal.” Despite, or perhaps because of its opacity as a concept, neoliberalism has emerged as a way of seeing the world’s political, economic, and social problems as interconnected. As political theorist Wendy Brown argues in her latest book, Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution, it is “globally ubiquitous, yet disunified and nonidentical with itself in space and over time” (21). Neoliberalism is both immanent and utterly submerged, now here and nowhere.

How, then, to understand and productively deal with a reality named neoliberal? According to Brown, it is not enough to say that economies are global, or that capital infects all social reality. On the one hand neoliberalism constitutes “specific economic and political reactions against Keynesianism and democratic socialism,” dismantling regulatory roadblocks for domestic and international markets (17). On the other hand, it converts “the distinctly political character, meaning, and operation of democracy’s constituent elements into economic ones” (Ibid.), producing marketized affects, discourses, and subjectivities that colonize other regimes of value. Although these interventions play out most notoriously in so-called “developing countries,” Undoing the Demos devotes its attention to neoliberalism’s stateside workings. Though published before Trump’s candidacy, Undoing the Demos offers an important diagnosis of contemporary American politics and ethics, a useful manual for understanding the insurgent force of economic reason in American life, and a warning about neoliberalism’s antagonistic relationship to democracy.

As if to anticipate Trump-era nostalgia for American progressive politics, Brown’s first chapter examines President Barack Obama’s social policy discourse as a neoliberal masterclass. In the speeches she examines, Obama links the country’s most pressing social justice issues, including racial discrimination, violence against women, and harassment of undocumented immigrants, with victims’ potential alternate futures as self-helping and self-realizing entrepreneurs. Brown writes: “In a neoliberal era when the market ostensibly takes care of itself, Obama’s speech reveals government as both responsible for fostering economic health and as subsuming all other undertakings (except national security) to economic health” (26). Neoliberalism means that socially progressive commitments “can no longer stand on their own legs” if “democratic state commitments to equality, liberty, inclusion, and constitutionalism” become “subordinate to the project of economic growth, competitive positioning, and capital enhancement” (26). The Obama fan club may grow substantially during the Trump administration. Yet years before prosperity gospel preacher Paula White blessed Donald Trump’s inauguration, he drew the often-tendentious messages of justice and accumulation close together.

Barack Obama’s social policy discourse as a neoliberal masterclass. In the speeches she examines, Obama links the country’s most pressing social justice issues, including racial discrimination, violence against women, and harassment of undocumented immigrants, with victims’ potential alternate futures as self-helping and self-realizing entrepreneurs. Brown writes: “In a neoliberal era when the market ostensibly takes care of itself, Obama’s speech reveals government as both responsible for fostering economic health and as subsuming all other undertakings (except national security) to economic health” (26). Neoliberalism means that socially progressive commitments “can no longer stand on their own legs” if “democratic state commitments to equality, liberty, inclusion, and constitutionalism” become “subordinate to the project of economic growth, competitive positioning, and capital enhancement” (26). The Obama fan club may grow substantially during the Trump administration. Yet years before prosperity gospel preacher Paula White blessed Donald Trump’s inauguration, he drew the often-tendentious messages of justice and accumulation close together.

Following these reflections on her own definition of neoliberalism, Brown offers a critical reading of Foucault’s as offered in his 1978-9 Birth of Biopolitics lectures. She and Foucault agree that neoliberalism is a form of “governing rationality,” meaning that it shapes the conditions of possibility for social, political, and economic relations, but she offers three modifications to his framework over the course of four chapters (though they are primarily concentrated in chapters two through four). She argues first that Foucault, writing within neoliberalism’s quiet, emergent swell in Europe, remained more concerned with the forms of reason neoliberalism offered to political subjects. In other words, he did not, and perhaps could not, imagine that political subjectivity as such might get colonized by economic subjectivity (65, 81). Foucault thus failed, according to Brown, to anticipate the ways human subjects as envisioned in the canon of economic and political theory—the one motivated to truck, barter, and exchange by their natural interest in the polis—would become ensnared, and their interests subsumed, within the unquestioned project of macroeconomic growth (85).

Brown’s third, more implicit critique of Foucault gnaws at the foundations of his famous claim that modern states concern themselves with the protection, division, and surveillance of human populations. By positing contemporary nation-states as subordinate aides to supra-national markets (27), wherein “every aspect of human existence is produced as an entrepreneurial one,” she suggests that individual humans find themselves in a flat field of capital alongside other laborers, consumers, as well as nonhuman means of production (65). If we take this analysis seriously, long-standing liberal concerns about human alienation from nature, or their replacement in the work force, each by way of machines, should give way to an excavation of how deeply devalued human life has become relative to the commodities that announce themselves, day by day, as more essential for life. Undoing the Demos contains a demand, however deeply submerged, for vigilant attention to the nation- and market-level re-coding of human value relative to non-human things, as well as the value of difference among humans, particularly in the Trump era.

Brown does not venture very far in this direction, for in her view if neoliberalism militates against the distinction between human life and capital, it does similar work on human differences and regimes of normativity.

As subjects continually code their lives in entrepreneurial and managerial terms, Brown argues, they come to disavow already-existing and continually-intensifying inequities that rig capital’s competitive fields, as well as their dependencies on other people and on social infrastructures (107). “Disavowal” figures centrally in legal discourses that have codified corporate personhood and chipped away at the conditions of possibility for collective organizing against exploitative employers and structurally-violent laws. Brown addresses and critiques the legal arguments that have allowed this to happen in cases such as Citizens United and Buckley v. Valeo in chapter five (see especially pp. 154-164).

As subjects continually code their lives in entrepreneurial and managerial terms, Brown argues, they come to disavow already-existing and continually-intensifying inequities that rig capital’s competitive fields, as well as their dependencies on other people and on social infrastructures (107). “Disavowal” figures centrally in legal discourses that have codified corporate personhood and chipped away at the conditions of possibility for collective organizing against exploitative employers and structurally-violent laws. Brown addresses and critiques the legal arguments that have allowed this to happen in cases such as Citizens United and Buckley v. Valeo in chapter five (see especially pp. 154-164).

Brown’s entire book is couched in the frame of neoliberalism as a threat to the very idea of “the rule of the people” as a fully-formed political possibility, let alone as a preferential option to corporate utopianism or security-state fascism. That provocative framing is in itself enough to open up specific and serious conversations about neoliberalism in religious studies research, in the classroom, and in the training of graduate students.

If Brown is even partially right about neoliberalism’s dramatic “stealth revolution,” then faculty and graduate students in religious studies must think clearly and specifically about how to contend with the weight it lays upon us, our colleagues, and our students. Graduate students, in particular, are no strangers to implicit pressures or even explicit injunctions from colleagues and professors to get exposure via conference presentations, regular blogging, and other entrepreneurial activities. We are encouraged to self-invest by working long hours with troublingly low compensation, and to divest from unprofitable activities like activism and romantic partnerships. Our non-male colleagues and colleagues of color suffer the brunt of these particular neoliberal pressures as they find themselves bearing the brunt of the “unprofitable” work of activism, child-care, and troubling gendered negotiations in the workplace.

None of us is a stranger to this seemingly distant phenomenon called “neoliberalism,” and so it must not remain a stranger to us. And it does not have to—Undoing the Demos is not a policy manifesto, nor is it overly populated by opaque philosophical terms; it articulates the underpinnings and effects of the phenomenon known as neoliberalism in accessible and workable terms. It thus stands, along with important works by Kathryn Lofton (2011; 2015), Craig Martin (2014), among others, as the foundation for a study of religion in our neoliberal era. These studies gesture in important ways towards the new and dangerous formations Brown outlines by shedding light on the commodification of religious things, the economization of the cultural idioms by which we seek fulfilment, and the enchantment of the secular world via the preacherly exhortations of tech-CEOs and media icons (see Lofton 2011).

Yet the needs of the day seem to demand more from us than fresh scaffolding on the study of religion and capitalism, religion and politics, religion and migration, or the study of evangelicalism. Perhaps they demand we intensify the kind of research Lofton and Martin’s work embody. Perhaps they call for a “post-Trump” study of religion, foregrounding neoliberalism’s role in the erosion of democratic values around the world, perhaps overturning current analyses of the interactions of religious systems with what we might call democratic values. After all, Donald Trump is on the tip of everyone’s tongue, and to a certain extent he must be, for a while at least. Perhaps neoliberalism, the neoliberal, and “neoliberalization” should, with Brown’s help, become watchwords on the job market and the lecture circuit, and all analytical maneuverings will bend their course toward that foggy terrain.

Yet the needs of the day seem to demand more from us than fresh scaffolding on the study of religion and capitalism, religion and politics, religion and migration, or the study of evangelicalism. Perhaps they demand we intensify the kind of research Lofton and Martin’s work embody. Perhaps they call for a “post-Trump” study of religion, foregrounding neoliberalism’s role in the erosion of democratic values around the world, perhaps overturning current analyses of the interactions of religious systems with what we might call democratic values. After all, Donald Trump is on the tip of everyone’s tongue, and to a certain extent he must be, for a while at least. Perhaps neoliberalism, the neoliberal, and “neoliberalization” should, with Brown’s help, become watchwords on the job market and the lecture circuit, and all analytical maneuverings will bend their course toward that foggy terrain.

At the very least, Brown’s work demands we take up neoliberalism on three basic analytical levels: the relationships subjects bear to each other, to their social worlds, and to the things they exchange; how those relationships sustain themselves within particular state formations that enshrine inequality and demand sacrifice of their citizens; and how state and non-state actors at all scales locate capital in landscapes of humans, objects, buildings, and communities coded as “religious” or “secular.”

Undoing the Demos is a startling book. In taking it to heart, we may run the risk of obscuring its utility by operating one-trick analyses, of finding the neoliberal in everything. A small price to pay, perhaps, for avowing what would otherwise be disavowed as simply the order of things. Where neoliberalism seems to be nowhere, our dialectical mantra must be: Neoliberalism is now here.

Isaiah Dylan Ellis is a doctoral student in religious studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. His current work on spiritual idioms in modernist architecture feeds his broader interest in the intersections of religion, economy, and urbanism in the Americas.

Notes

[1] Cornel West, “Goodbye American Neoliberalism. A New Era is Here,” The Guardian online, November 17, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/nov/17/american-neoliberalism-cornel-west-2016-election.

[2] George Monbiot, “Neoliberalism: The Deep Story that Lies Behind Donald Trump’s Triumph,” The Guardian online, November 14, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/nov/14/neoliberalsim-donald-trump-george-monbiot.