Giorgio Agamben. What is Real? Trans. Lorenzo Chiesa. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2018. 88 pages. ISBN: 978-1-5036-0737-8

Every mysterious disappearance assumes mythical tones, the subsequent fate of the missing person remaining indefinitely suspended when concrete and sufficient information is lacking: perhaps a second life somewhere far away, under an identity as new as false, as ‘real’ as unproven; perhaps the death somewhere else, which in the absence of a corpse cannot but remain presumed, ‘real’ only on the base of conjectures. This is especially the case of Italian physicist Ettore Majorana’s disappearance in 1938, whose mystery is thickened by a network of enigmatic correspondences and enriched by further mythical connotations, relating as much to his precocity and prodigy as to 20th century history and science.

In 1975 Leonardo Sciascia devoted a captivating book to this singular episode[1]. By carefully recollecting the fragmentary reports, the Sicilian writer retraces the physicist’s life, from the years as a promising member of the group of scientists gathered around Enrico Fermi, to his brief but intense trip to Germany in 1933, to study with Werner Heisenberg and Niels Bohr; from his long period of work in a state of voluntary reclusion, to his return to “normal life” in the late 1937, when he is appointed to the Chair of Theoretical Physics of Naples on the sole basis of his reputation. According to Fermi himself, Majorana is a scientist of neither second nor first category: he is a genius like Galileo and Newton[2]. And as in the case of many other geniuses, Sciascia is able to discern in his personality as much the intellectual sharpness and the prophetic vision, as the taste for theatricality and the exasperated sensibility[3].

When on the evening of March 25th 1938, the thirty-one year old physicist boards the Naples-Palermo mail-boat and vanishes forever, most think of a suicide, others of a retreat in some monastic area of southern Italy. Following this second trail, Sciascia advances a suggestive hypothesis: Majorana would have perceived what the scientists of second and first category failed to perceive, that the experiments on radioactivity carried out at the Physics Institute in Rome could lead to nuclear fission; Majorana, who in the years preceding his retreat from the world often said that physics was “on the wrong track,” would have glimpsed the terrifying and catastrophic consequences of the splitting of the uranium atom into smaller fragments. Hence the disappearance in terror and dismay, through which the physicist, according to Sciascia, turned his figure into a myth – a myth of the rejection of science[4].

In the recent What is Real? Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben returns to this unsolved enigma, offering a reading of it which, differently from the moral-psychological one put forward by Sciascia, is of a purely philosophico-metaphysical character[5]. By interrogating, with the clarity that distinguishes his style, the shift in the conception of reality brought about by modern physics, Agamben sheds further light on the case: with his decision to disappear – this is the suggestive idea at the core of the thin book –, Majorana would have turned his own person into the cipher of the statute of reality as it is expressed by quantum theory.

To corroborate this hypothesis, Agamben begins by analysing the content of the three letters written by Majorana on the same day of his departure and in the following day. While being the only certain documents at our disposal, these are permeated by a profound ambiguity which seems largely intentional and leaves them open to divergent interpretations. In the first letter, to his colleague Antonio Carrelli, Majorana announces his “sudden disappearance,” without however really disappearing right after it; in the second one, to his parents, he suggests a suicidal intent that is however denied in the following letter (“the sea rejected me”); in the third, again to Carrelli, he speaks of an immediate return to Naples, without however reappearing again.

The events evoked in the letters, then, never really correspond to the reality of facts. The only identifiable constant remains the accent on the neither subjective nor psychological motives of his decision to disappear (“it does not contain a single speck of selfishness”) and reappear (“do not think I am like an Ibsen heroine, because the case is different”). While the only real, albeit inexplicable, fact is Majorana’s irrevocable disappearance: “Equally certain and improbable”, writes Agamben, “in the literal sense of the term, it cannot be proved and ascertained at the level of facts[6].”

Keystone of Agamben’s argumentation is an article by Majorana, entitled “The Value of Statistical Laws in Physics and Social Sciences”(included as an appendix to Agamben’s text)[7]. Written during the four years of intense study between 1933 and 1937, but published only in 1942, four years after his disappearance, this essay deals with the passage from the causal determinism of classical mechanics to the purely probabilistic conception of reality introduced by quantum physics.

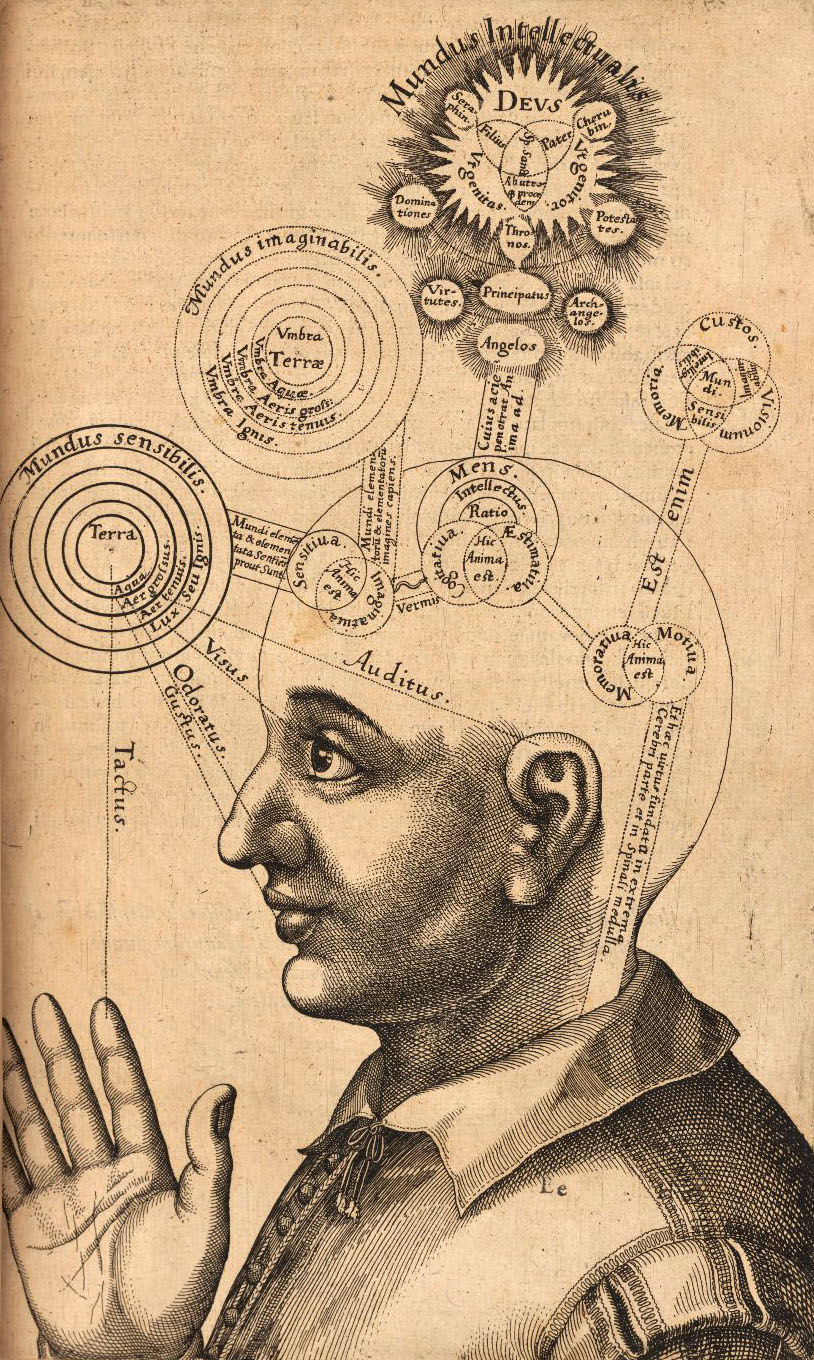

Two aspects of this transition are particularly highlighted by Majorana. First of all, a radical transformation of the notion of ‘law’, which within the new conception of nature assumes a purely probabilistic character. Natural laws – writes the Italian physicist – do not express an inevitable sequence of phenomena; rather, they possess a statistical character which only allows us to establish “the probability that a measure performed in a prepared system will give a certain result[8].”

Secondly, an aspect that just some years earlier brought Heisenberg to formulate the uncertainty principle: the lack of objectiveness in the description of an atomic system, as a consequence of the finite perturbation invariably exerted on it by scientific observation itself. This is the characteristic of quantum physics that Majorana holds to be the “more disquieting, that is, farther from our customary intuitions, than the simple lack of determinism[9].” Measurements are only able to grasp the state in which a system is led to by the experiment itself, rather than the unperturbed state of the system which remains unknowable[10].

Agamben carefully lingers over the conclusive passage of the article, where Majorana reveals the profound significance of the formal analogy between the statistical laws of physics and the statistical laws of social sciences. At first glance, the substantial difference between the unpredictable and isolated fact of an atom’s disintegration and the macroscopic facts registered by social statistics would seem to impede such analogy. However, Majorana argues that this does not constitute an “insurmountable objection:”

The disintegration of a radioactive atom can force an automatic counter to record it as a mechanical effect, which is made possible by an appropriate amplification. Ordinary laboratory devices are therefore sufficient to prepare a complex and conspicuous chain of phenomena that is commanded by the accidental disintegration of a single radioactive atom. From a strictly scientific point of view, nothing prevents us from considering it plausible that an equally simple, invisible, and unpredictable vital fact lies at the origins of human events. If this is the case, as we believe it is, then the statistical laws of the social sciences enhance their function, which is not only that of empirically establishing the outcome of a great number of unknown causes, but especially that of providing an immediate and concrete testimony of reality. The interpretation of this testimony requires a special art, which is not the least significant support of the art of government[11].

Sciascia found this conclusion “disturbing and alarming,” defining it as a “terrifying epigram[12].” Agamben, instead, thinks it is possible to identify within it something that goes beyond a subtle allusion to the destructive potentials of nuclear fission. The term “commanded” and the rather evocative final line, in particular, represent for the philosopher a crucial extension of the two aspects of quantum physics earlier highlighted. In fact, here Majorana seems to suggest that the defect of determinism of natural phenomena authorizes the investigator’s intervention, in order to command the phenomena themselves in a certain direction.

Once reality, as a deterministically causal sequence, is “suspended”, the intervention of the command becomes not only legitimate but necessary. If this is the case, the principle of uncertainty acquires a different meaning, representing not simply a stop sign on the itinerary of scientific knowledge, but rather an invite, for the investigator, to hold the reins of the experiment. The prospect of quantum physics is not really the knowledge of an atomic system, but rather its active determination. According to Agamben, what Majorana understood is that “science no longer tried to know reality but – like the statistics of social sciences – only intervene in it in order to govern it[13].”

In the middle sections of the book, Agamben dedicates intense pages to the history of the concept of probability (Gerolamo Cardano, Blaise Pascal, Pierre de Fermat) which will undoubtedly interest philosophers and historians of science alike. A conspicuous part of his attention, however, is dedicated to the contestation of the concept’s assumption by quantum theory. In particular, Simone Weil’s 1941 essay, “La science et nous,” allows Agamben to further expand Majorana’s considerations and connect them to coeval writings by Max Planck, Albert Einstein and Erwin Schrödinger.

The transition from classical physics to quantum physics entails, for Weil, the abandonment of science itself: “Without noticing, we lost science, or at least the thing that had been called by that name for the last four centuries[14].” More specifically, what we lost, according to Weil, is the formal analogy between natural laws and the image of the world founded on the experience of work, together with the notion of energy that from this derived. In the world considered as a continual juxtaposition of phenomena, quantum theory has suddenly introduced the discontinuity of atomic systems and the probabilistic character of the laws which regulate them. Weil’s fundamental intuition is that once science renounces to the paradigm of necessity and cause-effect relation, thereby assuming the unknowability of the realstate of a physical system, then reality is replaced by probability and statistical models.

This is what, according to Agamben’s reading, Majorana had foreseen just a few years earlier. And this is why his case demands a different reading. As one can infer from his article, rather than the historico-political implications of nuclear fission, Majorana realized the epistemological implications of an exclusively probabilistic conception of reality. His disappearance, then concludes Agamben, needs to be tied to this realization, as a strong objection to the probabilistic nature of the quantum universe.

As an event that is “at the same time absolutely real and absolutely improbable”, disappearance is “the only way in which the real can peremptorily be affirmed as such and avoid the grasp of calculation”[15]. With this event – as real as indeterminable and thus ungovernable – Majorana asked science the question that still awaits its answer: What is real?

In a letter to Max Born dated 29 April 1924, Einstein – another genius like Galileo, Newton and Majorana – wrote: “I find the idea quite intolerable that an electron exposed to radiation should choose, of its own free will, not only its moment to jump off, but also its direction. In that case, I would rather be a cobbler, or even an employee in a gaming house, than a physicist”[16]. Perhaps, one could speculate, Majorana really did end up being a cobbler or a croupier after vanishing into thin air.

Agamben, however, arrests his reflection before any conjecture on the brilliant physicist’s whereabouts. What we are left with is the fact of his disappearance. Not – as Sciascia maintained – as the epilogue of a religious drama, ultimate gesture in front of the premonition of the religious dismay that soon science would lead to with the creation of the atomic bomb. Rather, as a metaphysical drama, inspiration of a fundamentally philosophical question and, until now, sole answer to the question itself; event as real as improbable – exactly like the free jump of an electron exposed to radiation.

Filippo Pietrogrande is a PhD candidate in Philosophy of Religion at the University of Groningen. His current research interests primarily concern contemporary French philosophy and literary criticism.

______________________________________________________________________________

[1] Leonardo Sciascia, The Moro Affair and The Mystery of Majorana, trans. Sacha Rabinovitch (Manchester: Carcanet, 1987), 121-175.

[2] Ibid., 170.

[3] One example among many: Majorana who, one year before Heisenberg, formulates the theory of the nucleus made of protons and neutrons, only to then cast it into the waste paper basket and forbid Fermi to even mention it at a congress in Paris (ibid., 138-139). The complicated relation between Majorana and Fermi is also at the centre of director Gianni Amelio’s 1989 movie I ragazzi di via Panisperna (The Panisperna Street Boys).

[4] Ibid., 168-170.

[5] Giorgio Agamben, What is Real? trans. Lorenzo Chiesa (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2018). The subtitle of Agamben’s book, La scomparsa di Majorana (“the disappearance of Majorana”) – omitted from the English translation – is the original title of Sciascia’s book.

[6] Ibid., 6.

[7] Ettore Majorana, “The Value of Statistical Laws in Physics and Social Sciences”, in: Agamben, What is Real? 45-65.

[8] Ibid., 61-62.

[9] Ibid., 62.

[10] Agamben, 10.

[11] Ibid., 11-12.

[12] Sciascia, 155.

[13] Agamben, 14.

[14] Ibid., 15.

[15] Ibid., 42-43.

[16] Max Born, The Born—Einstein Letters 1916-1955: Friendship, Politics and Physics in Uncertain Times, trans. Irene Born (New York: Macmillan, 2005), 79.