This is the eighth lecture in an eight-lecture series. The most recent lecture can be found here.

The paper these lectures support is entitled “God, Christ, and Salvation”, but of these it seems that only the first two are actually addressed. You have heard eight lectures about “God”. So, what about salvation? Is this at all addressed, or is this as an issue simply relegated to the sidelines?

This would be strange indeed given the centrality of this concept within Christianity and, consequently, within Christian theology. One way of avoiding this difficulty is to show how salvation is actually woven into accounts given of God and into accounts given of the person of Jesus Christ. The latter in particular would appear evident. How could any Christology make sense if it doesn’t explain how this particular individual can be the cause of human hopes for salvation?

The same has, however, also be argued with regard to the doctrine of God. In particular where theologians have been wary of the confusion of the Christian God with the so-called God of the Philosophers (B Pascal) or the God of the metaphysical or the ‘ontotheological’ tradition they have emphasised the need to link Christian theology in every place to the underlying belief in salvation. The question then is not so much, “Is there a God?” or, ‘What are God’s attributes?’ but “Who is the God who made a covenant with his people?” and, “Who is the God who, in Jesus Christ, has revealed himself to enable salvation for all those who believe in him?”

These questions can of course be understood in a way that makes them not mutually exclusive, and generally speaking this view has been predominant while the existence of a supreme being was taken for granted by most. Thus, in most medieval and early modern theologians the doctrine of God progresses from the former to the latter on the assumption that those express knowledge about God universal to all humanity while the latter draw on knowledge that was obtained only through the Christian revelation.

The more recent history has been somewhat complex and cannot be recounted within a few words, but one may say that first the notion of revealed knowledge of God became problematic leaving natural knowledge as the only reliable source of ‘revelation’; in a second step the validity of such ‘natural’ knowledge of God was radically questioned. This then led to renewed interest in the God specific to the Christian message of faith in salvation through Jesus Christ.

This story by now is rather well known to you, and I merely allude to it here in order to emphasise once again to what an extent modern approaches to God are conditioned by the challenges to theistic belief that became prominent since the late 18th century. It is important to see that the nature of these responses could vary: while some would seek to withdraw to notions of God that could (seemingly or actually) be reconciled with modern criticism, others sought to defend specific Christian ideas about God in the teeth of this kind of criticism by maintaining that the criticism had been aimed at the wrong kind of target in the first place (even though they would concede that Christian theology had some responsibility for this mistake on account of its alliance with the metaphysical tradition).

What does this mean especially for the connection between the notions of God and salvation? The trajectory followed by theologians to be considered during today’s lecture is broadly described thus: they argue that our concept of God is strictly based on an inference from the Christian experience of salvation. Theological God-talk then is not really interested in ‘God’ as he may (or may not) ‘exist’ or ‘be,’ but in the God who exists or is ‘for us.’

God for us therefore is, quite aptly, the title of one of the most influential books devoted to this approach recently. That naïve reply to this will, I assume, inevitably be, ‘How can God be there for us if we don’t know whether he exists in the first place?’ We shall see in more detail later how theologians respond to this question – in many ways the quality of their answer to it determines the quality of their theological attempt. However, quite generally it seems clear that the answer must be given along the following lines. Of course, the God who is there for us must also ‘exist’ in some absolute sense.

Still, it makes for a substantial difference whether this fact is, as it were, deduced from his attitude to us about which we are certain prior to any abstract theological or philosophical ‘knowledge’ about his existence or whether we start from an attempt to establish God’s being hoping to move from there towards the assertion that this ‘God’ is also benevolent and in a loving, personal relation with human beings.

The claim is that the latter is definitely impossible whereas the former is not. In other words, it is one thing to argue that the God on whom believers are willing to stake their present and future existence, in whose providential guidance they trust and in whose salvific will they have faith must also exist and be omnipotent, omniscient etc. (because otherwise all these assumptions could not be maintained), quite another thing to claim that the cosmological principle allegedly established through the cosmological argument is also the loving God of the Christian tradition.

It appears then that thinking about God from a soteriological point of view avoids two major problems: it circumnavigates the failure of philosophical arguments for his ‘existence’ (insofar as this can be abstracted from religious experience of him), and it is firmly and solidly built on the fundamental assumptions of the Christian faith.

To gauge the extent to which this approach can or cannot stand in the face of modern challenges it is, however, important to see a further aspect here. Modern critique of theism targets, in one of its forms, specifically this type of theological argument. You may remember Feuerbach. He had argued that human beings project their own notion of perfection into an external being from whom they therefore expect the blessings which (Feuerbach thinks) they ought to work for themselves.

The soteriological foundation of theology is therefore in itself in danger of falling into the trap of modernist critique where it argues that simply from the fact that human beings trust in God and put their hopes into him it follows that belief in God is reasonable. Feuerbach (as well as later psychological critique) replies to this that from a human ‘need’ for God his reality does not follow – for human beings may well dream up an answer to their needs and desires.

It is partly for this reason that some influential 20th century theologians – not least Karl Barth – have been extremely reluctant to sign up to a direct short circuiting of theology with soteriological hope. Once again, to gauge the extent to which attempts in this direction have been successful it will be important to see how they manage to avoid what one may call the ‘Feuerbachian trap.’

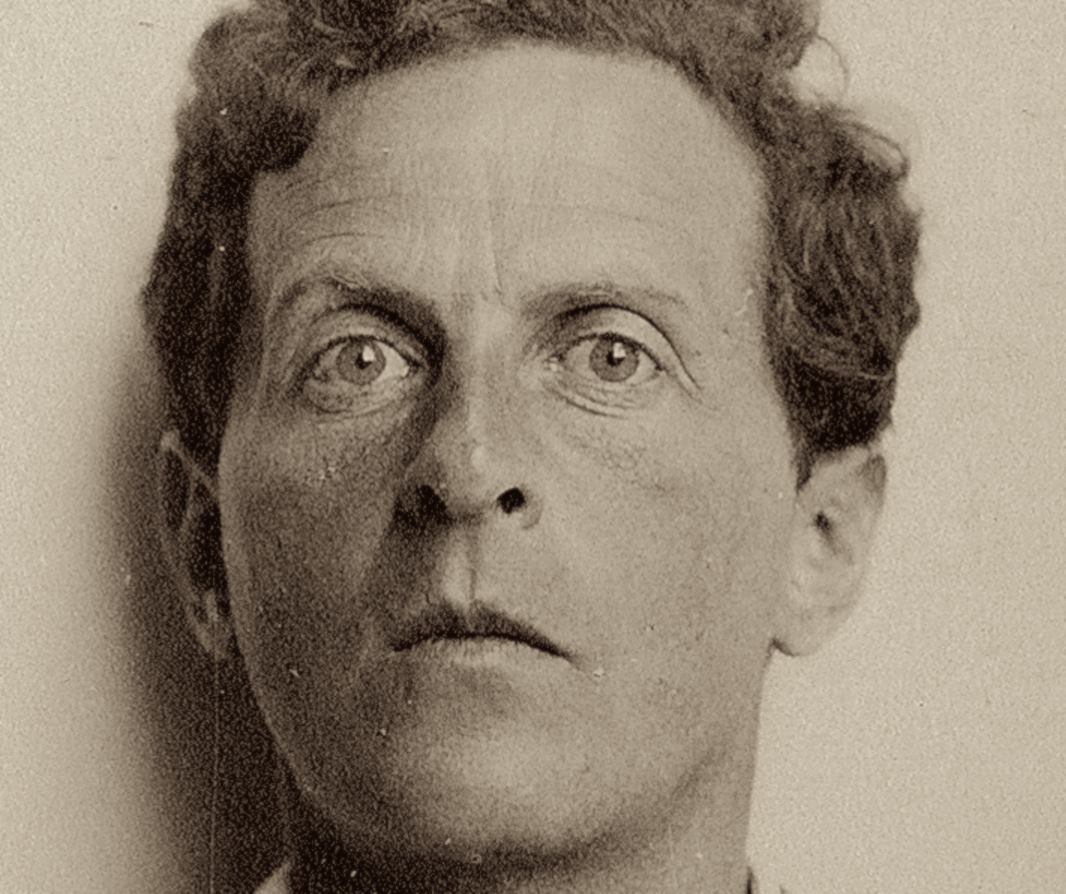

Of the three theologians we will look at today two, Karl Rahner and Catherine Mowry Lacugna, have framed this soteriological approach to the doctrine of God consciously in trinitarian terms. This gives us yet another chance to catch a glimpse of what has often been called the ‘trinitarian revival’ in 20th century theology. Before I come to these two Catholic theologians, however, I suggest casting a brief glance at Dietrich Bonhoeffer, arguably one of the most influential theologians of the 20th century, and his influence shows no sign of abating.

Bonhoeffer famously (and paradoxically) stated that a God who ‘exists’ does not ‘exist.’ This is perhaps the strongest version of the principle I have been expounding up until now. To see what Bonhoeffer means by it, we have to set it into the context of some of the novel ideas explored by him in his Letters and Papers from Prison. The challenge he seeks to address there is this, ‘What do a church, a community, a sermon, a liturgy, a Christian life mean in a religionless world?’

What does Bonhoeffer mean here by ‘religionless world’? This is not so easily decided; insofar as he seems to apply this to a process of secularisation and, on account of that, a gradual disappearance of ‘religion’ he may have been misled by some developments at his time, which later were not carried on in the same manner. Yet I think that for the core of Bonhoeffer’s insight the questions of whether religion in the modern world has actually come to an end and, if so, what kind of ‘religion’ this would be, are of limited importance.

For what Bonhoeffer wants to argue is in a sense independent of any such development. His point is that for Christians to approach God is to approach him through Jesus Christ. This means to see him in the context of salvation, but not so much our own individual salvation, but the salvation of the other, the salvation of the world. To find God through the encounter with Jesus leads, according to Bonhoeffer, to paradoxical thinking. God must be sought where God seems absent – in the unassuming human person from Nazareth and today perhaps in the middle of a seemingly secular world.

Bonhoeffer thinks that the God of traditional religion – as much as the God of metaphysics or of philosophy – is ultimately a way for Christians to avoid facing the really difficult and challenging issue of relating to God in the world. Locating God somewhere in the transcendent realm, defining him in a way independent of our relationship with him is not merely failing to understand him but is failing to respond to his call.

The task of the Christian is to follow Jesus, but to follow Jesus means to follow him into the world which – as the gospel of John calls it – ‘did not know him.’ This is not a pleasant endeavour, and it is therefore quite understandable that people try to avoid it. ‘Religion’ with its notion of divine remoteness is essentially one efficient and successful strategy for this Christian task, and it is for this reason that Bonhoeffer saw a glimmer of hope in a world that became ‘religionless.’

It is, nevertheless, absolutely crucial to see that his ideas were utterly different from those of the 60s liberals who claimed to follow in his footsteps. They thought Christianity was liberated from its fetters by giving up on traditional, ‘religious’ ideas, which happened at their time anyway. They felt they could buy into a zeitgeist while rejecting its seemingly anti-Christian character. They essentially affirmed everything about post-WWII secularisation, but claimed that this was not opposed to Christianity, but its realisation.

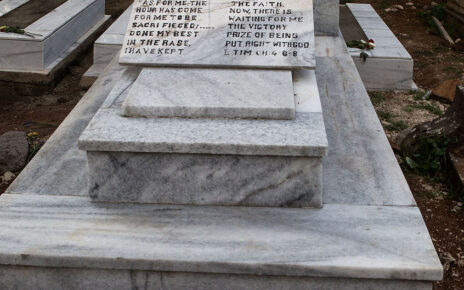

We merely have to recall that Bonhoeffer wrote his lines in a prison cell at the height of World War II to realise that he clearly cannot have been enthusiastic about the direction of contemporary developments. The godless world he calls upon Christians to embrace really is a bleak reality, and serving the zeitgeist in his case surely would have meant offering the comforting function of religion as an antidote against it.

So, the task of finding God in the world that does not seem to know him is, for Bonhoeffer, as difficult and paradoxical as it sounds. It is, once again, totally different from the identification of Christianity with historical or social progress. It is a way of understanding the call of Jesus to his followers that they must be prepared to ‘take up the cross and follow’ him (Mt 10, 38) based on the assumption that the world that rejected and crucified the Son of God cannot be expected to be a friendly place.

[Religious man] must therefore live in the godless world, without attempting to gloss over or explain its ungodliness in some religious way or other. He must live a “secular” life, and thereby share in God’s sufferings. He may live a “secular” life (as one who has been freed from false religious obligations and inhibitions). To be a Christian does not mean to be religious in a particular way, to make something of oneself (a sinner, a penitent, or a saint) on the basis of some method or other, but to be a man–not a type of man, but the man that Christ creates in us. It is not the religious act that makes the Christian, but participation in the sufferings of God in the secular life.

What does all this tell us about God? Is Bonhoeffer saying that Christianity must be prepared to give up God within a modern world that does not understand him any longer? It is easy to misunderstand him there. Christians must indeed be prepared to follow the path trod by Jesus to the point where he said, ‘My God why hast thou forsaken me?’ In this sense they must be prepared to give up God as a crutch to prop up their self-esteem or their orientation in the world or whatever other benefit bestowed by such a concept. They must be prepared to let go of the God of traditional religion.

Yet Bonhoeffer is confident that by accepting that practice they will discover God in a new and ultimately more meaningful sense. By sharing in the suffering of the world they will come to understand the God who because of his love for humanity shared in its suffering through his own Son. Thus, the expectation is that this particular practice is opening up to human beings an understanding of God in Christ drawn from the notion, developed specifically in the gospel of John, that God reveals himself in and through the abasement of Jesus in his passion and in his death.

God then cannot be known independently of Jesus and this for Bonhoeffer means independent of his suffering and his death. God then cannot be known except through his relation to the world and more specifically to us. Yet this relationship is only experienced by joining in a practice that shows the same solidarity with a world estranged from God that God himself showed in the Incarnation and which is sharply to be distinguished from an acquiescence or even an enthusiasm for its godlessness.

When we move from here to Karl Rahner (1904-1984) approaches our problem from a very different angle. For him the problem of the relationship between God and salvation is closely connected with what he perceived of the eclipse of trinitarian theology. He starts his famous essay on the Trinity, published at the time of the 2nd Vatican Council in 1967, with the observation that while the Church has maintained the trinitarian formula developed by the Church Fathers and codified by the Ecumenical Councils, much of Catholic theology and much of modern Christian life has become in fact merely ‘monotheistic.’

The dogmatic tract On the triune God is isolated from the rest of dogmatics which start from the much more foundational considerations about the oneness of God, and it is this tenet which is then carried through in the treatises on Incarnation and salvation. It is, Rahner observes, essentially ‘God’ who becomes human, bestows grace upon believers etc.

Why is this the case? Well, one important reason Rahner believes is that Western trinitarian development has actually cut off the inner life of the Trinity from essential theological questions concerned with the history of salvation. This is (at least partly) due to the sharp differentiation between what has come to be called the immanent and the economic Trinity.

What does this mean? At first sight, the differentiation is innocent enough and would seem almost inevitable. Once the complete equality between the divine Persons in the Trinity had been secured it was recognised as a danger that these Persons had, more traditionally been associated with various stages in the history of salvation: the Father with creation, the Son with Incarnation, the Spirit with the Church. Such an identification could be seen as reintroducing a hierarchy (after all the Father comes first!), but it could also seem to amount to a separation between them in their respective activities in relation to the world.

To avoid these unwelcome conclusions, the distinction was introduced between the activities of the Trinitarian persons in relation to the world and their mutual interrelation, which is in a sense indifferent to the latter. All the traditional language about substance and Person, about the origin of the Son through generation and so forth was now restricted to this latter notion of the immanent Trinity, which was strictly separated from its function within the history of salvation (economic).

The formula developed on the basis of Augustine’s trinitarian theology was that ‘the works of the Trinity are divisible on the inside, but indivisible on the outside.’ Yet this meant, according to Rahner, that any differentiation between the Persons was carried out in complete abstraction from human experience of God. Insofar as we are in relation to God in the history of salvation differences between the Persons are merely notional, not real. Yet this, Rahner argues, must mean that the Trinity itself becomes restricted to the abstract musings of theologians and separated from the spiritual life of the Church.

It is for this reason, then, that he introduced his most famous maxim into trinitarian theology that ‘the economic Trinity is the immanent Trinity, and the immanent Trinity is the economic Trinity.’ The fundamental idea of this seems clear enough; against the long-standing tradition of separating off the inner life of the Trinity from its involvement in the history of salvation, Rahner maintains that whatever the Trinity is, is revealed in its interaction with the world, and whatever God reveals of his own trinitarian being in that history, this is his own being. Theology must (and can only) draw on the resources of salvation history for understanding God, and it is, consequently, from this source that it has to establish whatever trinitarian theology it could ever have.

What does this mean in practice? Crucially, Rahner believes we need to develop a trinitarian interpretation of the Christ event itself. This ‘absolute self-communication of God to the world’ according to Rahner ‘symbolises’ the Trinity. It reveals God as Father in his absoluteness, as Son as the principle active in history, as Spirit who has been given to us and is accepted by us.

It is in this way that Rahner thinks his fundamental axiom of the identity of immanent and economic Trinity will help re-establish trinitarian thinking at the very heart of theology. Once again, God’s being is anchored in his salvific relationship with us. Rahner’s theology has received its fair share of criticism. It has been argued that it reduces God to a function of human religious experience. This is what I called earlier the ‘Feuerbachian trap’ in any such attempt. If God is essentially nothing but the fulfiller of our needs, desires and wishes, this may make him irreplaceable for us, but it doesn’t prove his reality nor the justification of Christian faith.

It is, of course, often overlooked that Rahner’s statement is not merely saying that the Trinity is nothing but the economic Trinity. He carefully formulates two symmetric statements: the immanent Trinity is the economic Trinity, and the economic Trinity is the immanent Trinity. He certainly attempts to identify the two, not reduce one to the other. His intention is to make God in his trinitarian being relevant again, not reducing the Trinity to a postulate of our human experience.

This Rahnerian intention has been emphatically affirmed and carried forward by the American feminist theologian Catherine Mowry LaCugna in her 1991 book God for us: The Trinity and Christian Life. In many ways it may be fair to say that she is merely drawing out the consequences of Rahner’s idea though with some modifications. She devotes much space to an exploration of Patristic trinitarian doctrine and attempts to show that the separation of immanent and economic Trinity really is the problematic Western heritage from Augustine. By contrast, the self-communication of divine Persons encountered in the Cappadocians would give much more significance to trinitarian theology today.

LaCugna is quite explicit about a soteriological foundation of the Christian doctrine of God (which for her is trinitarian). Yet her ultimate objective lies elsewhere:

The doctrine of the Trinity is ultimately a practical doctrine with radical consequences for Christian life. Trinitarian theology could be described as par excellence a theology of relationship, which explores the mysteries of love, relationship, personhood, and communion within the frame of God’s self-revelation in the person of Christ and the activity of the Spirit.

In other words, more than Rahner whose paradigm is ultimately Ignatian spirituality, LaCugna thinks of practice as the end of the Christian faith. This in a way links her with Bonhoeffer even though the latter did not develop the trinitarian aspect of his theology in the same way. Divine life is also our life, LaCugna states – once again the borderline between transcendence and immanence is intentionally blurred. Thinking God in a trinitarian way, for her more arguably than for others, really is tantamount to thinking him from a soteriological and practical point of view.

It is probably fair to say that much of the criticism directed at Rahner fits LaCugna’s trinitarian theology much more than it does his. In order to explain how God can be the ground of Christian life she essentially reduces him to a dimension of the human experience of salvation. Admittedly, this explains how he can be ‘useful’ for our own lives and relevant to modern Christian existence, and this is no small thing. Yet there is very little safeguard in Lacugna’s theory against the ‘Feuerbachian trap’ of a functional reduction of God.

Let me add a few words in conclusion of this series of lectures. They have given not much more than a glimpse of modern thinking about God. Much has remained unexplored – and I shall not give you a list of that for otherwise you might feel cheated!

And yet even this cursory exploration should have shown how much God is still on the modern mind. The fact that belief in him has been challenged has not eclipsed intellectual interest in him; on the contrary, it has if anything increased it.

At the same time, it has become clear to what an extent modern challenges have shaped debates and theories about God. And this not only in the sense that attempts to think and talk about God had to defend themselves against various forms of criticism directed against all such theories, but also in a more positive way. I think it would be a grave mistake to see modern theology essentially as a battle between forces inimical to religion and those who seek to defend it.

Much of what has been said against traditional theology has resulted from sincere reflection on what the Christian God should be; and much of what has been written in defence of Christianity has been built on those reflections even if, in the final consequence, the conclusions inevitably differed. I should therefore encourage seeing modern reflections on God neither as the last stand of confessional apologetics nor as a sell-out to modernist ideas, but as fruitful reflections on what is perhaps the greatest question ever to have occupied the minds of human beings.

Johannes Zachhuber is Professor of Historical and Systematic Theology at the University of Oxford. He is a Fellow of Trinity College. He earned his DPhil from Oxford in 1998 and obtained a habilitation in systematic theology at Humboldt University, Berlin, in 2011. His areas of specialisation include the history of Christian thought in late antiquity and the nineteenth century; secularisation theories; and religion and politics. He has authored or co-authored five books and edited or co-edited nine. He has written many articles and book chapters in all his research specialisations.