Georges Bataille, The Limit of the Useful. Translated and edited by Corey Austin Knudson and Tomas Elliott. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2022. Hardback. 360 pages. ISBN 978-0-262-04733-3.

The Accursed Share, one of the more enduring literary and philosophical projects undertaken by Georges Bataille, started a decade before its eventual 1949 publication as what he had been calling in notes, drafts, and correspondences The Accursed Share, or the Limit of the Useful (at times simply The Limit of the Useful).[1] In the Oeuvres Compléte, Gallimard editors used The Limit of the Useful to refer to what they considered an “abandoned” version of the text.

Previously unavailable to many readers, it offers a window into a transitional period for Bataille. One of those transitions is away from the “intense fragmentary accounts of experience within an ongoing series of philosophical and quasi-mystical speculations” that had been predominant in his earliest works (and never wholly dissipated), toward the somewhat more formal kind of academic writing that one finds in subsequent works.[2] The transitional nature of The Limit of the Useful is punctuated by the fact that its writing coincided with the production of two other texts, Inner Experience (1943) and Guilty (1944), which still indulged in the fragmentary, eccentrically self-reflective style of works that he had produced in the late 1920s and early 1930s (with passages that Bataille characterized as “not written in possession of myself”).

Other important transitions include his relationships with surrealism and with Communism, both of which will need to be seen in their respective historical contexts. Shedding new light on the outcome of The Accursed Share, Corey Austin Knudson and Tomas Elliott provide the first English-language translation of The Limit of the Useful, which should prove compelling for those with a particular interest in Bataille, in the intersections between Continental thought and religion, and for scholars of religious and cultural theory more broadly.[3]

Despite having worked at the margins of philosophy and in many ways being more personally involved with France’s art world than with its intelligentsia, Bataille is among the most prominent Continental theorists of the 20th century who consistently placed religion at the center of his thought. There are deep debts to Durkheim, Weber, and Mauss regarding the sacred, sacrifice, ritual, ecstasy, and community. Even so, his status among religion scholars today, though not insubstantial, remains understated and tends to attract those with specific interests in such things as medieval religion, eroticism, and mysticism – topics that he routinely addressed but that by no means exhaust his theoretical contributions.

To the extent that there is, for some, a degree of reticence toward his work, this may stem from a variety of factors: his reliance on centuries-old missionary ethnographic writings; what can seem like a tendency to valorize sacrifice and war; a pornographic bent; lack of lucidity in many of the pre-Accursed Share works; Nietzschean antagonism toward conventional notions of morality; questions about his relationship to Marxism and capitalism; and, although such things cannot be controlled, that his influence extends beyond the comfortable lineage of French intellectuals (Blanchot, Kristeva, Foucault, Derrida, Barthes, Baudrillard, Deleuze) to post-Deleuzian accelerationist strands (Nick Land, for example) that both attract and affirm elements of alt-right thought and by some accounts are its direct predecessor (Land’s only conventional monograph is The Thirst for Annihilation: Georges Bataille and Virulent Nihilism).[4]

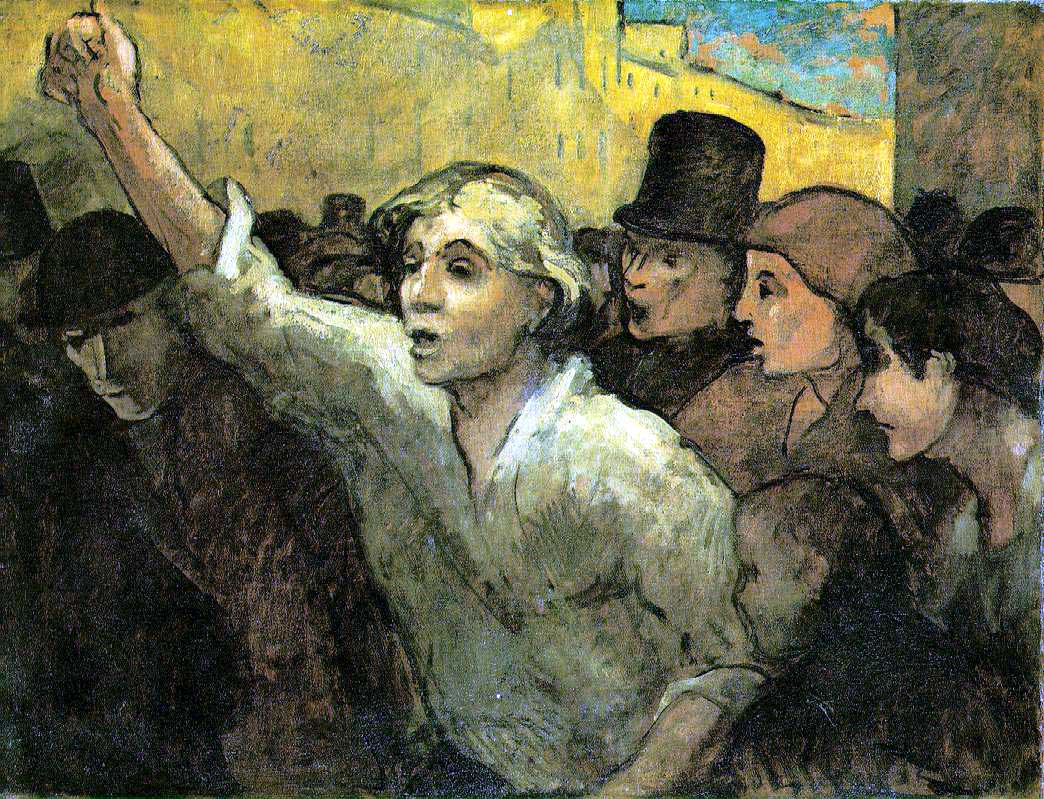

Part of what makes Bataille enigmatic owes to a mode of surrealist thought and expression with which The Limit of the Useful can be seen as grappling. Although much is made of Bataille’s falling out with André Breton, the preeminent surrealist spokesperson, the depth and duration of the friction between them and the degree to which Bataille was ever not engaging in surrealist practices is easy to overstate.

One way this is true is that while there are some differences between The Limit of the Useful and The Accursed Share (which will be discussed), long sections on primitive ethnography are common to both, as is a propensity to want to discover evidence within it of an approach to life, nature, and community whose suppression in modern societies Bataille sees as a sign of decay.

The temptation to read Bataille’s interest in primitivism as another instance of 19th-century-style anthropological romanticism is complicated by the role of ethnography in surrealism. Bataille’s central theme of “nonproductive expenditure,” which assigns value to that which surpasses utility, appears as early as 1933 in The Notion of Expenditure, at a time when he was deeply involved in France’s post-World War I surrealist scene. Amid surrealism’s many complex fissures and ex-communications (often owing more to temperament than ideological differences), Bataille spent the years 1929-1933 as the driving force behind a dissident strain of surrealism whose vehicle of expression was the journal Documents, which he edited.[5]

The differences between the fractious strands of surrealism are less important for an understanding of Bataille’s writing in texts like The Limits of the Useful than a recognition of key commonalities he shared with the surrealist project in general: a critique of that which is rational and socially useful; a willingness to shock with jarring juxtapositions and material regarded by bourgeois society as filthy and profane; an interest in primitivism and non-Western cultures as foils for the rational-scientific paradigm; and an ardently (it must be said) Left-wing sensibility, although not an entirely conventional one.

In addition to drawing from Mauss (whose studies of the gift and sacrifice are clearly prominent here), Bataille’s ethnographic source material in both The Limit of the Useful and The Accursed Share draws heavily from the 16th-century Spanish friar Bernadino de Sahagún, who wrote at great length about the people of present-day Southern and Central Mexico. Sahagún is often called the “father of ethnography” and was, to be sure, part of Spain’s settler colonial New World apparatus. Although endemic to the rise of European colonialism, by the early 20th century ethnography still had not yet fully professionalized. The manner in which surrealists took inspiration from African, Oceanian, and Mesoamerican artifacts collected in the Musée du Trocadéro in Paris reflects a situation in which neither surrealism nor ethnography were fully bounded or unified.

For issues of Documents, Bataille solicited works by intellectuals such as Mauss, who was at that time laying the groundwork for modern ethnological methodologies; artists such as Masson, Klee, Giacometti, and Picasso, whose 1907 Les Demoiselles D’Avignon is the product of time spent at the Trocadéro; and Marcel Griaule, who led the Dakar-Djibouti exhibition of artists and anthropologists to gather what the museum’s commission stipulated should consist of “ordinary” and “everyday” items from Africa, as opposed to items of a more formal “artistic” or “religious” nature that would have conflicted with the purview of the city’s more established museums.[6]

The resulting fragmentation and juxtaposition of the Trocadéro’s exhibits, combined with its displays of cultural sensibilities that cut against the grain of Western reason, lent themselves to surrealism’s aesthetic and political intuitions. Particularly when set against the backdrop of a world war that Lenin had described as “imperialist,” this encounter with cultural otherness took on resonances that ran counter to the logic of its 19th-century, colonially-inflected ethnographic and anthropological counterparts.

As James Clifford argues in “On Ethnographic Surrealism,” the war had cast into doubt the narratives of progress and order, compelling the early 20th-century avant-garde (from Cezanne’s fragmented landscapes to Cubism, Dada, and surrealism) to look to alternatives – psychologically within and geographically without – that better reflected the fractured realities they experienced. “Unlike the exoticism of the nineteenth century,” Clifford suggests that “modern surrealist ethnography began with a reality deeply in question … [As] artists and writers set about after World War I putting the pieces together in new ways, their field of possible selection had drastically expanded. The ‘primitive’ societies of the planet were increasingly aesthetic, cosmological, and scientific resources.”[7] In these respects, one can read The Limit of the Useful and The Accursed Share as surrealist texts.

What Clifford describes as surrealism’s “ironic experience of culture” is as evident in the essays and visual displays of Documents as it is a structuring mechanism for the arguments of The Limit of the Useful, where Bataille goes straight away into something that is only introduced a few pages into The Accursed Share (doing so at greater length and arguably to greater effect). Chapter 1, “The Galaxy, the Sun, and Man,” establishes what will be at once the Nietzschean starting point and the basis of an ongoing dialogue with modern science and primitive culture.

Bataille employs a cosmic framework to suggest that 1) like celestial bodies, life is not based on anything fixed but consists of energy and movement, so that reality is in fact a “dizzying,” foundationless “whirlpool,” 2) due to the activity of the sun, with its seemingly limitless expenditure of energy, in the “general economy” of life there is always an excess of energy that cannot be completely absorbed in utilitarian ways, and 3) whereas in Modernity the attempt to make all such expenditures productive tends either toward catastrophic ends, such as war, or toward nihilistic states that lack a genuine experience of life and freedom, primitive cultures were more circumspect. They understood better and acted upon the need to engage in nonproductive expenditure, primarily through religion, ritual, sacrifice, and cultures of the gift.

Part of what Clifford is calling the “irony” of these procedures is produced by the way Bataille’s argument incongruously pairs recent scientific discoveries about the cosmos (e.g., Einstein’s relativity) with the cosmological knowledge and practices of non-Modern and non-Western cultures, both of which he saw as challenging conventional scientific attitudes and their corresponding political and economic rationalities. Bataille’s discourse remains surrealist in its juxtapositions – at once empirical and mystical, scientific and religious, contemporary and primitive, Western and not – gesturing toward a porous boundary that subverts the solidity of the kind of rational utility at which The Limit of the Useful takes aim.

In the clearest statement of a thesis that one finds in The Limit of the Useful, Bataille stresses that losing oneself in relation to life’s energy economy is more natural and meaningful than a life lived in view of the ends of self-interest, self-preservation, and accumulation: “Loss is necessary not to gain some kind of result but for the glory of losing oneself.”[8] The sun, as in so much of Bataille’s writing, plays a central role throughout. Its radiance “lavishes” energy, making it, for Bataille, the consummate symbol of non-recuperable self-loss, expenditure in the form of a pure excess that cannot be assimilated and necessarily has to be squandered, which he describes as a kind of luxurious wastefulness.

Primitive culture responds to the sun by partaking in its “glory” through rituals of unreciprocated giving, whether through sumptuous feasts and festivals or through the sacrifice of wealth and life. Like solar imagery, the language of “gloriousness” to describe the ecstasy of self-loss and unproductive expenditure is more prominent in The Limit of the Useful than in The Accursed Share. Bataille’s rhetorical choices are at this point closer to the poetic form of prior works like The Solar Anus, paradoxically in search of ways of using language to convey what is beyond the limit of experience and comprehension.

In contrast with primitive culture, conventional modern attitudes and social arrangements draw on “the common idea of the ground as a foundation for real things.” The “error of a fixed earth” and the “illusion of an immutable foundation” deprive the modern attitude of an awareness that “there is no isolable state that it could belong to.” The non-isolability that Bataille conjures through science-myth metaphors of the sun and the earth, ground, or soil sets in motion a whole range of implications for what it means when people instead “open themselves up, lose themselves,” orienting life around the “gift of self” rather than utilitarian self-interest. Such an orientation de-objectifies reality and deindividuates subjectivity. It appeals to that which is non-autonomous, fully relational, and contrary to the compulsion to accumulate. “The star is radiant, and our soil is cold. The star lavishes its power: our soil divides itself up into particles that are greedy for power” (Bataille’s emphases).[9]

As it evolved into the final form of The Accursed Share, Bataille’s way of expressing these claims began to synthesize self-loss with nonproductive expenditure in a more analytical fashion, so that what comes to the fore is a critique of the notion of unlimited growth. In The Accursed Share, what had initially been given the form of the quasi-mystical gloriousness of losing oneself in the sun (as an image of nonproductive expenditure) has taken on the feel of a text on political economy, which is how Bataille began describing the project in its later stages.

And yet, there is no total metamorphosis from myth and mysticism into science, philosophy, or political economy, nor would there ever be such neat distinctions for Bataille. It should be noted that, to the extent that either text is engaging with political economy, they do not make strong distinctions between ecology and economy. The central claim of Bataille’s “general economy” is not only that it prioritizes loss over gain and nonproductive over productive expenditure. It is also to be understood as inclusive of, and therefore more encompassing than, economies of wealth.

All expenditure, whether of wealth or life, ultimately derives from the play of forces enlivened by the energy that permeates the cosmos through the radiance of stars: “The living organism,” Bataille would later write in The Accursed Share, “in a situation determined by the play of energy on the surface of the globe, ordinarily receives more energy than is necessary for maintaining life; the excess energy (wealth) can be used for the growth of a system (e.g., an organism); if the system can no longer grow, or if the excess cannot be completely absorbed in its growth, it must necessarily be lost without profit; it must be spent, willingly or not, gloriously or catastrophically.”[10]

This is the shared premise of both “books” – the necessity of self-loss, of expending energy and wealth without profit or gain. In The Limit of the Useful, Bataille’s initial focus on sacrifice and potlatch is only the beginning of a narrative about the historical decline of nonproductive expenditure and its “catastrophic” consequences for modern society. He finds evidence of a decline in the transition from medieval Catholicism to Protestantism, with its austerity, frugality, and utilitarian work ethic, and in industrialization, in which unparalleled growth depends on the reduction of life to labor and in which excess profit, or surplus, is not enjoyed or squandered but recirculated into projects whose sole purpose is the continuation of self-perpetuating growth.

Another noteworthy difference between the two texts stems from the fact that The Limit of the Useful, which he started in 1939, was written in the shadow of the Great Depression and responds directly to it. Today’s reader will likely find relevant and compelling Bataille’s discussion of financial speculation, which is largely absent in The Accursed Share. Bataille sees the economic crisis of the early 1930s as an example of the kind of catastrophic effect that can be attributed, in at least two ways, to the principles set forth by his thesis. The first is what Marx, who saw its irony as a symptom of capitalism’s inherent contradictions, called crises of overproduction.

When overproduction leads to decreasing profits, capitalists are forced to turn against their own forces of production by destroying inventory and shedding labor. “Lost without profit,” excess “must be spent, willingly or not, gloriously or catastrophically.” Bataille also examines the element of play and “the gamble” at work in financial speculation, whose willingness to risk everything he sees as a latent expression of the “glory” of nonproductive expenditure (comparing Wall Street’s frenzied atmosphere to the feasts and festivals that once embodied the sumptuous squandering of wealth), but one that is misplaced and still circumscribed by what is otherwise an economy of limitless growth that reduces human life to the status of useful things.

Bataille’s critique of capitalism in The Limit of the Useful tracks closely with Marx’s criticisms of its artificially limitless, self-perpetuating growth and its dehumanizing qualities, with Marx’s view of humans as fundamentally social beings, and with Marx’s vision of forms of community in which the individual is fully realized and in which the goal is not greed, wealth, or growth. It would be a mistake to read Bataille too strongly in the direction of a lapsed Marxist since these themes remain resonant throughout his lifetime. On the other hand, there is some friction between Marx’s emphasis on basic need satisfaction and Bataille’s sense that there should be occasions in society for forms of extravagant expenditure that are not tied to uses.

In that sense, Bataille could say that the problem with capitalism, particularly in the decadent era of speculation leading to the Great Depression, is not its propensity for lavish indulgence, but that its “luxury is off kilter.”[11] Similarly, it is not the fact that crises of overproduction periodically compel capitalism to sacrifice its own wealth and resources. Rather, the problem is with its “failure to recognize necessity behind certain acts of squander.”[12] Reminiscent of Heidegger (with respect to Being), Bataille suggests that in capitalism, there is a kind of latent memory of the glory of nonproductive expenditure, but it is masked by forms of cultural forgetting.

We have fallen into ignorance “that we must resolutely waste the excess energy that we produce,” and as a result of our forgetting, “this excess wastes us more than we waste it” (70). As such, we have arrived at a tautological place where we produce too much for no other purpose than what is useful for growth alone. And yet, capitalism – a “tentacular system [that] does not expend except on the condition that it absorbs more than it loses” – continually finds itself, “willingly or not,” compelled to submit to states of loss.[13] Of that fact, the Great Depression was a case in point for Bataille.

By 1949, when what began as The Limit of the Useful was finally published as The Accursed Share, Bataille’s thinking had become less oriented by the Depression than by a postwar situation in which capitalism had rebounded, on the one hand, and in which, on the other hand, reports about Stalin’s ruthlessness were becoming increasingly widespread (soon to be disclosed by Khrushchev in a speech at the 20th Congress in 1956), adding to what was already known about the conditions in Russia and the change of course away from Lenin’s “world revolution” toward the policy of Socialism in One Country.

Bataille’s discussions of Stalinism and the postwar global economic system (under the heading of the Marshall Plan) at the end of The Accursed Share do not appear in The Limit of the Useful, but they accentuate the ways in which both versions of the text are attempts to weave together domains – from nature to politics and economics – that Bataille argues have been too narrowly defined and that participate in entangled ways in a much larger set of relations encompassing all of life – a “general economy.”

Despite its absence in The Limit of the Useful, it is worth recalling Bataille’s reading of Stalinism and postwar capitalism in The Accursed Share, because these interpretations of mid-century geopolitics help to clarify the nature and scope of the project that Bataille was imagining ten years earlier as he set about writing a book that began with “the galaxy, the sun, and man.” Like other surrealists, Bataille had for some time already distanced himself from Stalin’s Communism. In the final version of The Limit of the Useful (The Accursed Share), we are given justifications for those misgivings in a way that integrates them with his “general economic” outlook.

“Soviet communism closed itself firmly to the principle of nonproductive expenditure,” writes Bataille about what was required for the rapid development of what had previously been an industrially backward nation. “It did not do away with the latter by any means, but the social transformation it brought about eliminated the most costly forms of such spending and its incessant action tends to demand the maximum productivity from each individual, at the limit of human powers.”

Referring to Stalin’s state capitalist reversion of proletarian dictatorship (rule of the proletariat) into a dictatorial relationship over the proletariat aimed at maximum productivity, Bataille went on to argue that “the very nation that had almost perished from its inability to reserve a large enough share for growth, by a sudden inversion of its equilibrium reduced to a minimum the share that used to be given over to luxury and inertia: Today it only lives for the limitless growth of its productive forces … An immense machinery was assembled in which individual will was minimized with a view to the greatest output. No room was left for whimsy.”[14]

Bataille’s footnotes indicate that everything he wrote for these final “political” sections of what would become The Accursed Share was based on his (evidently voracious) reading of recent texts published between the years 1944 and 1949. Full of current data, they allow him to form an idea of the United States, in its role as a facilitator of the new global economic order (through the Bretton Woods system), as somewhat ironically playing a part that was the contrary of Stalin’s resort to purely productive expenditure. To rebuild Europe and to create a more stable world economy, and in what amounts to “the negation of the rule of profit,” it “was necessary [for the US] to deliver goods without payment: It was necessary to give away the product of labor.”[15] Through the Marshall Plan, in other words, the US “offers an organization of surplus against the accumulation of the Stalin plans.”[16]

Having previously examined in both versions of the text the role of Aztec kings in lavishing their people with extravagant feasts and festivals, Bataille is suggesting that the general economy of the planet has led to a situation in which the new superpower is compelled to lavish Europe with the costly “gift” of cheap loans and development aid money, for allies and former enemies alike, through “a mobilization of capital and its exemption from the common law of profit.” He knows that the US does not approach this new role without an eye toward self-interest: “The contribution of five billion dollars is vitally important for Europe, but the sum is less than the cost of alcohol consumption in the United States in 1947.”

But what is important is that the expenditure of 2% GDP represents a loss that would otherwise have abided by the law of a “restricted economy,” an economy of profit, utility, and self-interest: “Without the Marshall Plan, this 2 percent could have gone in part to increase nonproductive consumption, but since it is chiefly a matter of durable goods, in theory it would have been used for the growth of the American forces of production, that is, for increasing the wealth of the United States.”[17]

Bataille is uncharacteristically sober in his assessment that what appears to be “in the world’s interest” is very likely to emerge as being “in America’s interest” – astute for a text published one year after Keynes’s failed negotiations with the American Harry Dexter White, at Bretton Woods, solidified the US dollar as the world’s reserve currency. In any case, he concludes that “a general point of view requires that at an ill-defined time and place growth be abandoned, wealth negated, and its possible fecundation or its profitable investment ruled out,” for that is the inescapable nature of the general economy.[18]

Critics have argued that Bataille’s affinity for luxurious waste and his seemingly favorable remarks about postwar America’s world-stabilizing “nonproductive expenditure” mark him as overly endeared to capitalism. This seems off given Bataille’s further suggestion that US postwar expenditure would only have happened because of the role of a revolutionary Marxism: “A primary error is in thinking that a moderate, reformist agitation would ensure this evolution by itself. If the agitation that is due to the communist, revolutionary initiative did not take a threatening turn, there would be no more evolution. [One] would be wrong to imagine that the only successful effect of communism would be the seizure of power. Even in prison, the communists would continue to ‘change the world.’”[19]

I include these recollections of the text that The Limit of the Useful laid the groundwork for and ultimately became because they help clarify Bataille’s standing in two respects. The first is that he never stopped being a surrealist, despite references to Breton as an “old religious windbag” whose “swollen abscess of clerical phraseology” and “degrading idiocies” are those of a “false revolutionary.”[20] Bataille would go on to collaborate with Breton again after these exchanges, but more importantly, even in its most (more or less) refined states, Bataille’s writing consistently dealt with the themes and luxuriated in the juxtapositions that surrealism marshaled to undermine reality and champion everything that refuses to conform to the useful.

The second is that Bataille never stopped being a Marxist and a revolutionary thinker, despite sharing the same misgivings that almost every serious thinker had about Stalin, and despite an effort to place postwar US capitalism within a dialectical theory of historical change. His ruminations in The Limit of the Useful about the nature of limitless growth are not far, after all, from Lenin’s attempt to show (in Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism) that capitalism had entered a phase in which unrestricted growth was exhibiting its own internal contradictions by becoming imperialist, anti-competitive, and monopolistic.

If there is a consistent thread throughout The Limit of the Useful, one whose relevance should persuade today’s reader to take seriously its enduring value, it is that, in Bataille’s own words, “life or wealth cannot be indefinitely prolific and that the moment always arrives when they must stop growing and begin to spend” – not on that which is instrumental or profitable, but on that which serves no other purpose than to enliven the human experience.[21]

Matthew Waggoner is Director of the Urban Studies Program and Chair of the Department of Philosophy and Religion at Albertus Magnus College in New Haven, Connecticut. He is the author of Unhoused: Adorno and the Problem of Dwelling (Columbia University Press, 2019) and co-editor of Readings in the Theory of Religion: Map, Text, Body (Routledge, 2016).

[1] Georges Bataille, The Accursed Share: An Essay on General Economy, Volume 1: Consumption (New York: Zone Books, 1988). References hereafter to The Accursed Share are to volume 1 only.

[2] Fred Botting and Scott Wilson, “Introduction: From Experience to Economy,” in The Bataille Reader (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 1997), 8.

[3] Georges Bataille, The Limit of the Useful, translated and edited by Corey Austin Knudson and Tomas Elliott (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2022).

[4] There was much reporting in the late 2010s about Nick Land’s drift toward “intolerant opinions,” leading to his departure from the University of Warwick, and about the affinities that Steve Bannon saw between his own ideas and those of Land and his accelerationist collaborators. See Andy Beckett, “Accelerationism: How a Fringe Philosophy Predicted the World We Live In,” in The Guardian (11 May 2017).

[5] Documents is available through Bibliothèque nationale de France (gallica.bnf.fr/). On surrealism, see Maurice Nadeau, The History of Surrealism, trans. Richard Howard (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 1989), and André Breton, What is Surrealism? ed. Franklin Rosemont (New York: Pathfinder, 1978).

[6] Bataille also included photographs of ancient medallions from the collections he studied at the Bibliothèque Nationale, where he was employed. Among them is one that features the figure of a “dieu acéphale,” a headless god, which is a symbol that Bataille would later draw on, beginning in 1936, in the formation of a so-called “secret” intellectual society, Acéphale. It was in the group’s short-lived journal (in which he collaborated with artists André Masson and Marcel Duchamp and with philosophers Roger Callois, Pierre Klossowski, and Jean Wahl) that Bataille wrote vehemently against Nazi appropriations of Nietzsche’s philosophy. Beneath the title on the journal’s cover appeared the words “Religion. Sociologie. Philosophie.”

[7] James Clifford, “On Ethnographic Surrealism,” in Comparative Studies in Society and History (October 1981, Vol. 23, No. 4), 542.

[8] Bataille 2022, 102.

[9] Bataille 2022, 7-9.

[10] Bataille 1988, 21.

[11] Bataille 2022, 69.

[12] Bataille 2022, 66.

[13] Bataille 2022, 73.

[14] Bataille 1988, 158-160.

[15] Bataille 1988, 175.

[16] Bataille 1988, 173.

[17] Bataille 1988, 179.

[18] Bataille 1988, 182.

[19] Bataille 1988, 185.

[20] Georges Bataille, “The Castrated Lion,” in The Absence of Myth: Writings on Surrealism, trans. Michael Richardson (New York: Verso, 1994), 28.

[21] Bataille 1988, 181.